SIX-PART SERIES : SHOW PICTURES ‘WEST OF IMAGINATION’

NEW YORK — The West isn’t simply a spot on the globe, but a place in the mind, a land that has inflamed the imaginations of Americans and of the world. It was a place of adventure and derring-do, a place to encounter Nature and primitive people, a stage to play out the drama of manifest destiny.

The imagination saw the West first, often through the work of intrepid artists who accompanied the explorers and lived with the Indians.

That is the territory explored by “The West of the Imagination,” a six-part series that premieres this week on public television. (“The West of the Imagination” starts tonight at 8 on Channel 50 and tonight at 9 on Channels 15 and 24, while Channel 28 will carry the series Thursdays at 8 p.m. starting this week.)

William H. Goetzmann, a professor of American history at the University of Texas and winner of the Pulitzer Prize for his 1967 book “Exploration and Empire,” created the series, which was produced by KERA-TV in Dallas.

Actor James Whitmore is the narrator and host.

“The basic idea is to show the way in which image-makers, that is non-print image-makers, saw the West, and secondarily how that gradually began to be distributed to the public too,” Goetzmann said.

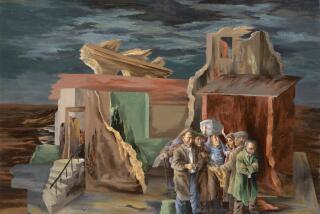

The story starts with the Louisiana Purchase, and the paintings of George Catlin, Karl Bodmer and Alfred Jacob Miller, which portrayed the Indians and mountain men. It continues with the story of landscape painters such as Albert Bierstadt, the cowboy art of Frederick Remington and Charles Russell, and on to the show-biz wild West of Buffalo Bill, William S. Hart and Willie Nelson.

If you’re going to invest six hours in watching “The West of the Imagination,” you might want to consider spending $34.95 for the companion book written by Goetzmann and his son. Otherwise, you’ll be left with dozens of questions that aren’t answered on the screen.

For instance, the series barely has time to show a few of Bierstadt’s eerily illuminated landscapes but no time to talk about how he was influenced by European landscape painters or his contemporaries in New England.

“As you can guess, a lot of stuff fell on the cutting-room floor,” Goetzmann said in a telephone interview. “A lot of my instincts toward making comments like that were rebutted” by his collaborators.

“This is not an art series,” Goetzmann said, “and we don’t deal with aesthetics or technique or the relative value of artworks. What I want to know about the art is, what does it tell us about the culture?”

One of his goals was to show the vast range of paintings and photographs of the West, to go beyond the well-known work of Remington and Russell. “What I was interested in showing is that there is a lot of good Western art, and it’s incredibly varied,” he said.

It’s a point, Goetzmann believes, which is not appreciated by his fellow Americans. In the exhibition of 101 American masterpieces that went to Paris a couple of years ago, he said, only two paintings were of the West.

The Old West seems to have slipped out of the national consciousness. Prime-time television hasn’t had a horse opera such as “Gunsmoke” or “Wagon Train” in years, and the Hollywood Western epic “Heaven’s Gate” has become a synonym for failure on a grand scale.

Goetzmann, however, doubts that the Western drama is dead.

“I feel sure they are coming back. You see things like the enormous sales of anything Louis L’Amour writes. The number of people who go West for vacations and touring is enormous,” he said.

“The world is awfully interested in the cowboy and the Indian, the mountain man and Mickey Mouse. They are major contributions to the world galaxy of heroes.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.