RADIO DRAMATIST OBOLER: THE PLOT’S THE THING

Plots, Arch Oboler was saying, are everywhere.

“Here we are, three men having breakfast in a coffee shop. What could be more ordinary? We make trivial conversation. We debate whether the orange juice is a little sour. But then I say, ‘All right, which one of us is going to kill Mama?’ ”

Yes, indeed, that would set a plot in motion very nicely. You don’t even need to see it. The voice of a waitress asking, “Which one a ya ordered the waffle?” sets the scene perfectly. As a teaser for a radio program, let’s say, the vignette would be almost irresistible.

Oboler should know, of course. By his best estimate, he has written something like 850 radio dramas, commencing in the 1930s when both he and the medium were very young. “Lights Out” was the series that established his reputation. It ran late at night, very late as it seemed in those days, 11:30 to midnight.

“These stories are definitely not for the timid soul,” Oboler as narrator would say in his quietly resonant voice. “So we tell you calmly and very sincerely, if you frighten easily, turn off your radio now .” And then he would add, as if he were flushing out the last of the faint-hearted, “Lights out, everybody!”

The series was an adornment of early radio, a spiritual predecessor of “The Twilight Zone,” “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” and “Amazing Stories,” all the enterprises that suggested there is unthinkable surprise and deadly mischief forever lurking behind the prosaic surfaces of life, just beyond the eggs over easy and the faintly sour orange juice.

The vast market for audio cassettes, ravenous in its appetite for new material and new old material, has now engulfed Oboler as well. A Minneapolis outfit called Metacom, which offers a considerable catalogue of radio material, is releasing two volumes (two half-hour cassettes or four shows altogether) “Lights Out Everybody,” the sound remarkably well-preserved nearly a half-century later. Metacom also plans to offer the Oboler plays for radio syndication, placing them back where they began.

In a characteristic play of the Oboler esprit, “Revolt of the Worms,” a snippy and unpleasant rose breeder takes his long-suffering wife and an aide to a remote hilltop to do some secret experiments, and discovers that his super-special fertilizing efforts have created monstrous, carnivorous earthworms whose bores are four feet across, long before “Dune.” The play makes effective use of a stream-of-consciousness technique that Oboler thinks he was the first to use in radio. It is all cheerfully shivery.

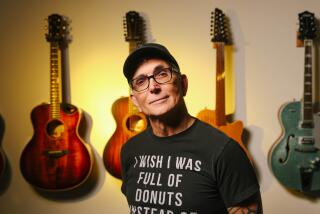

Oboler, now a stout 76 and given to wearing jumpsuits like Winston Churchill and Martin Ritt, has lived for 46 years in a house that Frank Lloyd Wright designed for him in the Malibu hills. He published his first story in the Chicago Daily News when he was only 10. “It was about an amorous dinosaur and I won a contest with it. But when I went to the newspaper in my short pants to collect the money, they saw how young I was and gave me a camera instead. I never forgave them.”

He attended the University of Chicago but seems to have figured out early that his gift was a fertile flow of stories that seemed as natural as breathing. Chicago was becoming a major center of creative radio, and Oboler successfully bombarded NBC in particular with his stories.

He was soon writing plays for “First Nighter” and for Don Ameche’s “Chase and Sanborn Hour.” The “Lights Out” series ran for a dozen years on NBC, then CBS and Mutual. Thanks to a favoring vote from Gen. David Sarnoff, Oboler moved from late night to prime time with a new series called “Arch Oboler’s Plays.” He published a collection, “Plays by Arch Oboler,” the first time, he believes, that radio dramas were preserved in print.

Only recently, he discovered 16-inch acetate recordings of 11 plays broadcast in wartime and featuring some stellar names, including Bette Davis as a New England schoolteacher who picks up a hitchhiker who turns out to be a very lost and bewildered Adolf Hitler.

Ingrid Bergman starred in another of the shows, called “Strange Morning.” She is a nurse, telling the GIs at a hospital that the war in Europe was over. The war wasn’t yet over when the play was written and broadcast, but it was a grim, prophetic study of postwar problems: a black GI not eager to confront peacetime racial prejudice again, GIs with grievous mental and physical disabilities for whom peace offered little cheer. There are even rumbles of Cold War troubles to come. Metacom plans to release cassettes of these plays early in 1987.

Like most fantasists, Oboler has written not only to divert and entertain but to comment, and he notes that he dealt in those early days with everything from abortion to the problems accompanying automation.

In 1952 he did the first major 3-D movie, “Bwana Devil.” He predicted that 3-D would become an important segment of Hollywood production (and several dozen 3-D films were in fact made), but the nuisance of the glasses proved an insuperable obstacle. Now, Oboler says, keep your eye on holographic movies.

But his passion is still with what he calls “the theater of the mind”: radio, with its extraordinary power to stimulate the imagination.

“If you’re dealing with living human beings,” Oboler says, “you don’t need special effects. We didn’t even need particularly special sound effects. Just voices, and some music.

“And plots.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.