The Flesh and Blood of a 6.7% Jobless Rate

With the official unemployment rate holding at 6.7%, proponents of reductions in taxes and government spending are proclaiming the triumph of “free-enterprise” economic policies as a means of reducing both unemployment and inflation. Before we join the celebration, however, we had better take a closer look at what a 6.7% jobless rate means.

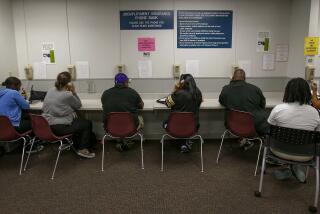

Almost 8 million workers are the flesh and blood of 6.7% of the labor force. Even if this figure accurately counted all Americans who can’t find a full-time job, it would be a tragic waste of human resources. In fact, the official jobless rate understates the problem of unemployment in America by about half. By adding 5.8 million “underemployed” (involuntary part-time workers) and 1.1 million “discouraged” (those who have given up hope), the National Committee for Full Employment calculates that 12.3%, or nearly 15 million people, cannot find a full-time job.

I wonder how many home and farm foreclosures, bank failures and ghost towns these figures represent. How many broken marriages? How many young people have to forgo their dreams of a decent education? How much illness, crime, spouse and child abuse, alcohol and drug addiction arises when the government decides that 15 million citizens are expendable hostages in the war on inflation?

Policies that deny 15 million Americans a decent job are an investment in social decay. Parents with decent jobs are providers and models for their children--and a force for community stability. Other social goals--safe streets, decent housing, adequate medical care, positive race relations--can come only from a base of full employment. A new generation is now growing up in homes where parents are without work. With no role models at home, where will the children learn about the work ethic? With declining education and training opportunities, where will they learn job skills and work habits that are essential for productive employment?

We know that government cannot accept the entire burden of educating and training the unemployed. But if the 1980s have taught us anything about private enterprise, it is that the private sector cannot do it alone, either.

Government can make a great difference by protecting workers from sudden unanticipated layoffs, by supporting fair-trade policies that stop the unbridled export of American jobs, by investing in public-works projects and by enacting tax and regulatory policies that provide incentives to employers to hire more workers.

The prevailing attitude in Washington seems to be resignation. Politicians often concede that full employment is a noble goal, but one that can’t be achieved. This ignores the moral issue. We can’t decide our social ethics on the basis of how difficult they are to fulfill.

For too long we have listened to the economists explain why we can’t have full employment. I think that we need to tell the economists to show how we can provide enough jobs for Americans who want to work.

We must not ask whether full employment will be simple, convenient or cheap, but whether tolerating massive unemployment is morally right or wrong. If the alternative to a full-employment economy is to wait for greater prosperity, to tolerate in silence the shattered dreams of 15 million Americans who have been frustrated in their search for decent jobs, then our choice is clear. Getting policy-makers in government and industry to accept moral responsibility for full employment is the challenge that accompanies this choice.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.