In Sierra Madre : Councilmen’s Prayers Strike Sectarian Note

For as long as Sierra Madre residents can remember, council meetings in their tiny community at the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains have opened with the Pledge of Allegiance and a short prayer composed and delivered by a council member.

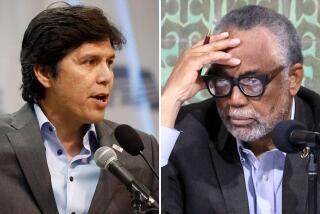

More often than not, these prayers--like the one given a few weeks ago by Councilman Roy Buchan--have been unmistakably Christian, asking for divine guidance for the five-member council and invoking the name of Jesus.

The practice, while time-honored, places Sierra Madre at variance with other cities and county agencies that also begin their meetings with a prayer, but one given by an outside minister or rabbi. Mindful of the line separating church and state, these clergy typically speak to universal themes and avoid the mention of Jesus.

Some council members acknowledge that the practice, in which they take turns delivering the invocation, excludes non-Christian residents who may attend council meetings. But they deny that it violates the First Amendment ban on any official establishment of religion. They say the prayers simply reflect their personal thoughts and, as such, do not have the imprimatur of City Hall.

“I’m afraid we don’t give enough consideration to the fact that some of our residents are Jewish or Buddhist,” Buchan said. “It might be a little uncomfortable for them to sit through it, although it’s not intended that way.

“But we’re not trying to convert anyone. And nothing would prevent a non-Christian who got elected from giving his own prayer.”

But Evelyn Schaefer, a 41-year resident of Sierra Madre who is Jewish, said she could not recall the last time a Jew, Moslem or Buddhist was elected to the City Council in this mostly Catholic and Protestant community of 12,000.

“I’m against any prayer that’s denominational, and I’ve been against that in every social or professional group I’ve belonged to,” said Schaefer, who assisted her husband in his accounting business and was once an active member of the Chamber of Commerce and Southern California Accountants.

“After all, you have all kinds of people in a group or community,” she said. “You have Christians and non-Christians, and it’s not right to exclude any of them.”

Deeply Ingrained

The use of prayer to open a legislative session or public meeting is deeply ingrained in the history of America. Every state legislature except the Massachusetts Senate routinely opens its sessions with an invocation.

The U.S. Supreme Court acknowledged this tradition in a 1983 ruling that upheld the Nebraska Legislature’s use of a single chaplain affiliated with a specific religious denomination to open its sessions with prayer.

“To invoke divine guidance on a public body entrusted with making the laws is not, in these circumstances, an ‘establishment’ of religion or a step toward establishment,” Chief Justice Warren E. Burger wrote for the majority in a 6-3 decision.

But Julian Eule, a professor of constitutional law at the UCLA School of Law, said the Nebraska case differs in two important ways from the use of prayer in Sierra Madre. A chaplain and not an elected official composed and delivered the prayer. In addition, the prayer had been nondenominational since a Jewish legislator objected in 1980.

‘Tends to Blur Distinction’

“While history may provide a tradition of having ministers deliver a prayer, I doubt there’s a tradition of having the public officials themselves cite the prayer,” Eule said. “When prayer is invoked by an elected official, it tends to blur the distinction between church and state and weakens the argument that prayer is protected.”

A Times survey of 15 cities in the San Gabriel Valley found that 10 of them opened their council sessions with an invocation. All 10 had a minister or rabbi deliver the prayer. City officials said these clergy are brought in on a rotating basis, often through a particular ministerial alliance, to avoid the appearance that government and religion are one.

Several cities have had difficulty getting rabbis or Buddhist clergy to deliver an invocation.

“We have a ministerial society, but it represents only 11 churches. There are no temples or mosques in the group,” said Connie Lara, assistant city clerk for Azusa.

“One of our city employees who is Jewish tried to get a rabbi to deliver our prayer every so often but was unsuccessful,” said Monrovia City Clerk Phylis McCarville.

One-Paragraph Prayer

Rabbi Perry Netter of the Temple Shaarei Tikvah in Arcadia said he delivers an invocation once a year before the Arcadia City Council. Netter, whose synagogue includes several Sierra Madre residents, said his prayer consists of one paragraph that begins with “Heavenly Father” and ends with “Amen.”

“I think prayer before a public body should speak to universal themes. If I happen to be present at a meeting where someone offers a prayer in Jesus’ name, then I’m excluded from that.

“I think all faiths have enough in common that we can find language that includes all of us.”

Sierra Madre City Councilman Sam D. Simpson said he tries to promote truth and unity and love and peace in his short prayer. In the 43 years he has lived in Sierra Madre, Simpson said, he has never heard a complaint about the city’s practice.

“I’ve heard back from Chinese and Japanese residents who have complimented me on my prayer,” Simpson said. “I don’t think the prayers that we give can be considered offensive to anyone.”

Councilman Buchan, for one, thinks it might be time for a change.

“A nondenominational prayer might be a good idea,” he said. “Maybe that’s what my next prayer will be.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.