Fugitive Couple Win Custody of Boy : Birth Mother, Foster Parents in Court Battle

BAKERSFIELD — Just before daybreak on Aug. 3, 1984, Jim and Cindy Meek took care of one last bit of business before becoming fugitives from the law. With a piece of lettuce, Jim lured Crip, the pet tortoise he’d had since childhood, out from under the house and loaded him into the Ford Courier pickup-camper hidden in the Meeks’ garage.

Then, before the neighbors were up and about, the Meeks slipped out of town and headed north.

Treasured Mementos

Their cargo included two dogs, $13,000 in cash (most of it from a second mortgage on their home), their TV and VCR, a few treasured mementos--and their foster child, 3-year-old Joseph Turner, for whom they had been waging what they believed to be a losing battle for custody.

On Aug. 20, when the Meeks did not show up for a scheduled court hearing, Kern County Superior Court Judge Henry E. Bianchi issued a warrant for their arrest. The charge: felony child stealing. The Meeks, if caught, faced a maximum of four years in prison and $10,000 in fines.

Today, back in Bakersfield after hopscotching across the Western United States and Canada and living under assumed names during 14 months on the run, the Meeks are now Joey’s legal guardians. If all goes according to their plans, they will also be his adoptive parents before the boy turns 6 in June.

But the Meeks’ decision to take the law into their own hands angered authorities, shocked family and friends, and posed a dilemma even for the attorney who handled their case. “Was this a bold move to protect a child, or was it a criminal act? It’s a real fine line,” says Christian Van Deusen, the lawyer who represented the Meeks through much of their contest with the law.

Solid Citizens

When the couple left notes telling friends and relatives they were about to become fugitives because they “couldn’t bear to give up the baby,” Jim and Cindy Meek were solid citizens, hometown kids who for the eight years of their marriage had scrimped and saved toward a secure financial future.

They left behind five properties in which they had a total equity of $133,000; four would be foreclosed on. They also left behind the comfortable life style afforded them by Jim’s $43,000-a-year superintendent’s job with a company that services oil wells.

“It cost us everything we had,” Cindy said, adding, “I didn’t think about what we were giving up, or what we would become. I had just one goal in mind.”

Making the Decision

There had been hours of soul-searching, Jim said. “Were we leaving for the right purpose? Were we being selfish, or was Joey better off with us? In our minds, we knew. I had always wanted security, but I didn’t think twice about giving it all up.”

In June of 1985, the Meeks, homesick and broke, contacted Van Deusen, a Santa Ana adoption attorney. Eventually, he and co-counsel Lee Felice of Bakersfield negotiated a plea bargain under which the Meeks pleaded guilty to misdemeanor child stealing and received three years’ probation. On Oct. 11, 1985 they came home to Bakersfield to renew their fight for Joey in the courts.

That fight took a year but, by last December, the Meeks had convinced the court that they were the child’s “psychological parents,” that the months as a family in hiding had cemented the bond. They were made Joey’s legal guardians, and they hope the adoption will become final next month.

But others, including a lawyer for Joey’s birth mother and some of the social workers for the Kern County Department of Human Services who early on opposed the Meeks in their fight, have questioned both their suitability as parents and the morality of rewarding them for breaking the law.

Jay Christopher Smith, the court-appointed attorney for Jerry Lynn Turner Hernandez, Joey’s mother, asks, “What are we saying to people--kidnap the child if you have to? Delay, delay, delay and then we’ll let you have the child because now he’s bonded to you? That stinks. There are a lot of people out there who want children and will do all sorts of crazy things.”

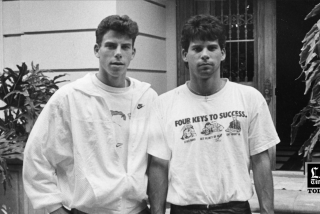

When Jim Meek, now 32, and Cynthia Meek, 29, childless after six years of marriage, were told by doctors that they could not have children, they thought of adoption and, as a first step, decided to take a foster child--”to see if we could love someone else’s child like our own,” Cindy said. Joey, then 13 months old, was placed in their home in July of 1982.

The blond, brown-eyed child, diagnosed as “developmentally delayed,” had been removed from another foster home. A dependent of the Juvenile Court, he had been placed in protective custody at his mother’s request in November, 1981, when he was 5 months old, after she had run away with him from the Bakersfield foster home where she was living.

She was only 17. At the time she contacted authorities, she and the baby were sharing a motel room in nearby Wasco with Turner’s girlfriend and she had one jar of baby food and no money, according to court documents.

When Joey came into the Meeks’ home eight months later, he was, by Cindy’s assessment, lagging about three months in development--”He couldn’t walk. He couldn’t say anything.” Within four months, she said, he had caught up.

From the beginning, Cindy said, he was a difficult child--”He would throw temper tantrums, bang his head against the wall or against the head of whoever was holding him.” He cried incessantly, and he was a biter.

‘He Needed Us’

Even so, “After three days, I was so attached to him I couldn’t give him up,” she said. “He needed us. We really needed him. He made us a family.”

Jim, admittedly, had reservations at first about this little stranger who was disrupting their lives.

As ordered by the court, Cindy would drop Joey off for regular supervised visits at the Welfare Department (the former name of the Department of Human Services) “was with his mother. Soon after the October visit, Turner made a temporary move to Los Angeles and, for almost six months, had no contact with Joey. After three months, the Meeks had started thinking about adoption. Cindy said, “We had heard that you could have a child freed on abandonment after six months. We were counting down the days. Then, two weeks before (six months), she came back” and resumed the weekly visits.

In November, 1982, a Juvenile Court referee warned that unless Turner demonstrated her ability to parent, her child might be placed for adoption. The court wanted assurance that she would get psychological counseling, build a stable and loving relationship with the child, and establish a proper home.

The Meeks, believing that all these conditions were not being met, at first sensed a climate favorable to them. At a special hearing in late September, however, a social worker recommended that Joey be returned to the custody of his birth mother, who was by now living with--and would later marry--Vincent Hernandez, a 34-year-old unemployed farm worker.

Psychological Evaluation

In December, 1983, the Meeks filed a petition for freedom from parental custody and control and a Superior Court hearing was set for late January, at which time Smith was named as Turner’s attorney and the court ordered a mental evaluation of Turner by two psychologists.

One concluded that Turner was not competent to meet even her own needs and recommended adoption planning. The other concurred that Joey “should not be remanded to the care of the natural mother.” A probation officer recommended that Joey go to the Meeks.

Nevertheless, the Welfare Department “was determined to fight it, tooth and nail,” as Cindy Meek saw it. By June, the Meeks said, they “had a sense we were losing. We started talking about what we were going to do.” By July, they were convinced they would lose. Jim said, “I looked at Cindy and she looked at me. What happened in court didn’t matter.”

There were second thoughts about running away. They asked their attorney what options would remain if they lost in court and were told there would be no appeal. “We knew if Joey was ever back in the system, we wouldn’t get him,” Cindy said. “We knew it was hopeless.”

Cash from the second mortgage in hand, with Jim identifying himself as “Jim Martin,” they bought a 1979 Ford Courier pickup. Jim laughed and said, “Being not very good at being criminals, we bought it right in town.”

The Meeks and Joey headed for Canada, stopping the first night at Grants Pass, Ore.

Canada was a mistake. There were no jobs in the oil fields. So, the Meeks drove south, to Louisiana. At a cemetery in Morgan City, they searched the grave markers, looking for people with birthdates close to their own who had died as infants. They decided to become James and Cynthia Patow, even though they weren’t sure how to pronounce Patow.

To establish Jim’s identity, they forged his new name on her high school diploma and obtained a new birth certificate, Cindy said. “It was real easy.” With two IDs he was able to get a driver’s license and a Social Security card. Jim worked briefly as a hand on an oil rig and then as a handyman for their landlord in Lafayette, La., where they lived for two months.

Jim worried that “We weren’t getting anywhere. And the wages were 40% less than in Bakersfield. And the mosquitoes were so bad and the cockroaches were huge. They’d fly in.”

Still, they weren’t ready to call it quits. They had always wanted to move to the San Diego area and, Cindy said, “We decided to follow our dream.” In a new van, they headed West.

Despite their fears, it appears virtually no one was looking for them. On Aug. 17, exactly two weeks after they fled, the Bakersfield district attorney, acting on evidence brought by the Kern County Welfare Department, had filed a felony child stealing case. The Welfare Department had then obtained a warrant for the Meeks’ arrest (bail: $25,000 each) and delivered it to the Sheriff’s Department.

But the warrant was never served.

Fell Through the Cracks

Sheriff’s Comdr. Frank Drake, asked if it’s possible the case simply fell through the cracks, replied, “Yeah. It sure is.” Drake suggested that it would have been the Welfare Department’s responsibility to do the investigation. Bill Curbow of the Department of Social Services said, “I don’t know who goofed. We made a report. I think the feeling was that you make a report of a missing person, that’s asking for an investigation.”

Simply delivering a warrant, even a felony warrant, to the sheriff’s office means little unless the case is assigned to an investigator, Drake said. He likened dropping off a warrant at the sheriff’s records division to handing information to a newspaper business office clerk and thinking “it has been assigned to an investigative reporter.”

Turner, who by this time had a daughter with Hernandez, made efforts on her own to get something going. She told a reporter at the time that to have Joey taken from her would be “like taking a piece of your heart and throwing it away or something. It don’t matter how many kids I got, there’s still one always missing.”

Meanwhile, the Meeks, wondering why no one seemed to be after them, reached California and camped at Carlsbad. One night, very late, they drove to Bakersfield, where relatives told them the investigation appeared to be on hold. Even so, they were careful not to divulge their exact whereabouts.

In December, Jim got off-and-on gigs in the oil fields in Long Beach and they rented a small house. But the realities were an ever-dwindling money reserve, illness, car trouble and his sagging self-confidence.

By May, the Meeks had decided to return to Oklahoma, where Cindy’s grandparents had offered free housing. But the story there was the same--no jobs. Increasingly, they began thinking of the possibility of going home. Cindy had clipped from a California newspaper a story about attorney Van Deusen and a complex adoption case. On June 15, she said, “I got up my nerve and called him.”

Reluctant to Take Case

Van Deusen recalls that he was reluctant to take the case. As the adoptive parent of a child whose birth mother had once attempted to get the child back, he acknowledges he “had a problem” with the fact that the Meeks had elected to steal Joey. The flip side of the coin was his conviction that, as policy, “social servants continue to press for reunification (of children) with the birth parent where it is absolutely hopeless.”

Finally, Van Deusen said, he “believed they ran and hid because they felt they had to do this to protect Joey.”

To pay Van Deusen’s retainer, Jim borrowed $3,500 from his former boss in Bakersfield. Then, in late August, they headed for Santa Paula, Calif., where there were jobs in the oil fields.

The Meeks now had a pager through which they could receive messages from her mother in Bakersfield. Van Deusen was to call the mother when there was news. Finally, on Oct. 10, he called with a message for the Meeks: They were to come to Bakersfield the next day.

As Cindy remembers, “I thought he had it all worked out where we wouldn’t lose Joey at all because I had told him that unless he’d give us a guarantee we couldn’t come home. I’d given up on coming home.” Van Deusen says he told them, “There are no guarantees, but I know you’re not going to go to jail, you’re not going to be booked.”

The Meeks no longer retain Van Deusen as counsel and the relationship is less than warm. They say they still owe him $34,000, with interest, and suggest the fee was extravagant. “He’d gotten our life back for us and we are grateful,” Cindy said, but “there’s no way we could pay it. We had no choice but to file bankruptcy on him.”

Van Deusen said, “I thought I had just about accomplished the impossible. This child was not just any child. This child was a ward of the Juvenile Court.”

And he points out, “They paid no fine. They served no time. They don’t even have a police record.”

The Meeks knew Round 2 was going to be tough the moment they walked into West Kern County Municipal Court with Joey the morning of Oct. 11, while Van Deusen pleaded their case in Juvenile Court. “My heart sank,” Cindy said. “It looked like the whole Welfare Department was there.”

Added Jim, “And they looked like the cat that swallowed the canary.”

They agreed to plead guilty to misdemeanor child stealing (because the Meeks were involved in a custody battle at the time, they were not charged with kidnaping). But Dist. Atty. Ed Jaeckels said there was no deal--unless they handed Joey over first. “What could we do?” said Cindy. “They’d have arrested us going out the door.” Asking for a minute alone with the boy, she assured him they’d be back for him in a couple of hours. “I told him to be brave and try not to cry,” Cindy said. “Then Jim started crying.”

Then three social workers took Joey and left.

For two months, Joey was at A. Mariam Jamison Children’s Center, where Cindy and Jim visited him once a week for an hour and Jerry Turner and Vincent Hernandez, who were by then married, also visited weekly.

The Meeks launched a get-Joey-back campaign, tying yellow ribbons around their trees and their friends’ and neighbors’ trees and distributing flyers describing how the child had been “snatched from his parents” by the Kern County Welfare Department. “WE’RE MAD,” it said. “GET MAD WITH US!!!”

In December of 1985, the Meeks went to court to try to get Joey back. Social worker Susan Jennings recommended during three days of hearings that they be granted custody, saying they were “the lesser of the possible evils.” Jennings felt Cindy was “overprotective” and said she perceived Jim as an indifferent father.

He shakes his head and asks, “Why would a person give up everything they had? That doesn’t make sense.”

Superior Court Commissioner William T. Helms decided there was little chance of successfully reuniting the child with his birth parent in the near future and awarded the Meeks temporary custody. Jerry Turner Hernandez, who was given bi-weekly visitation rights, protested to a local reporter, “It’s very unfair.” She vowed, “I’m still going to fight.”

Hernandez visited the child once, in February.

In November, 1986, in Superior Court, the Meeks again filed a petition for freedom from parental custody and control, this time on grounds of abandonment. On Dec. 5 their petition was granted, by default, in a 15-minute hearing when Hernandez did not show up. The Meeks were made Joey’s legal guardians.

Forfeited Appeal Right

Two weeks later, the Welfare Department dismissed its interests. The Meeks had won.

They have had no contact with Hernandez since February of 1986. In January, Hernandez was notified of the granting of the petition for freedom from parental custody and control. By failing to respond within 60 days, she forfeited her right to appeal.

In February, Bakersfield attorney Melvin Thompson, acting for the Meeks, filed a petition to adopt. Anticipating problems with Kern County, even though they point out that they were not convicted of a felony, they have opted for an independent adoption and are now undergoing routine evaluation by the state Department of Social Services.

Reflecting on the case of Joey Turner, Bill Curbow, senior program manager in the Kern County Department of Human Services, said: “Our first responsibility is to the child. I’m sure we were not comfortable necessarily with the idea that they did steal the child. The law dictates that reunification (with the birth parent) be our goal. It doesn’t say reunification with the ideal parent. She may not be the perfect parent, but if she is an adequate parent, then that’s where the child should be.”

Jay Smith says his client, Jerry Turner Hernandez, gave up her child without an appeal because she was “beaten down by events. . . . It was too painful for her. There was no point in dragging things out any further.”

He said, “She has expressed to me great sorrow and regret and feelings of disheartenment over the shabby way she was treated by the system. That includes the social welfare system under which children become dependents of the court, as well as the court process that comes after that.”

He depicted Turner at the time she relinquished custody of Joey to the county as an unskilled, jobless, single teen-age mother who “wanted to make sure her child was safe and taken care of.” He said she later “did everything she was supposed to do” to get him back.

Said Smith, “The net result of this (case) is to reward foster parents who violated their contract as foster parents, and the law itself.”

In January of 1985, saying she needed money to search for her child, Turner sued the Meeks and was awarded more than $100,000 for child stealing and emotional distress. The Meeks, then in hiding, lost by default but their properties were in foreclosure and there was no money. Later, they declared bankruptcy.

Hernandez, who now has three children from her marriage and is rearing her husband’s two sons, “would like to have Joey back,” Smith said, “but she recognizes that’s not going to happen and she’s not going to try and stir up the waters any further. She knows that is only going to cause more distress for Joey.”

‘Absolute Malarkey’

While he conceded that “her intelligence level is not as high as the normal person,” he described as “absolute malarkey” psychologists’ reports characterizing her as unable to care for the child.

Patricia Randolph, who as deputy county counsel represented the Welfare Department in court following the Meeks’ return, said, “By law, my clients’ goal and duty is to protect and serve the best interests of the child. Given the very difficult circumstances, that is what they, in fact, attempted to do.”

She added, “To my knowledge, we’ve never had a situation like this come up before.”

Later, having won their custody fight, the Meeks found that the child, after two months in a public facility, was emotionally unstable. He has been in therapy and, Cindy said, he still “doesn’t have the confidence to do anything,” even though he now tests at, or above, his age level in all areas and is performing well in school. She describes him as a loner, afraid to interact with the neighborhood kids.

Would they do it again? “We’d have to,” Jim Meek said.

Cindy disagreed--”We wouldn’t just run off. We’d find an attorney and start fighting.” Her husband added, “We didn’t leave because we wanted Joey for ourselves. We wanted Joey to have the home that he should have.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.