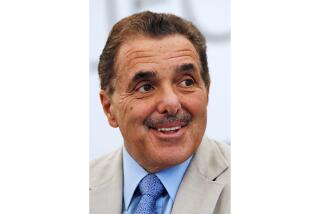

PHIL HAWLEY’S TALL ORDER : Retailer Expects New Spark From Old-Line Stores

It was nearly 5:30 p.m. in Washington on July 28, and an attorney for Carter Hawley Hale Stores was racing a deadline. Thanks to a helpful chauffeur and an understanding SEC official, he finally got the good word and relayed it to associates.

Across the country at the retailer’s Los Angeles headquarters, Chairman Philip M. Hawley took a call in the executive dining room, where colleagues cheered at his wide grin and thumbs-up sign. On the eve of Hawley’s 62nd birthday, this was the best possible gift: the government’s go-ahead for a sweeping restructuring of the Los Angeles institution.

“I have enjoyed having the idea, working on it and overcoming the challenges, because I think it is so uniquely right,” Hawley says. Stockholders are expected to ratify his proposal Aug. 26.

At an age when many executives might be thinking about that fishing cabin in Idaho or retirement in the south of France, Philip Metschan Hawley--long a fixture on the Southern California business and social scene--is embarking on perhaps his biggest undertaking. To a great degree, his reputation--along with the futures of more than 30,000 employees--is at stake. Few Los Angeles executives are so closely identified with their companies.

The challenges are many. Carter Hawley, for years geared to growth and acquisitions, is paring down, and in the process shedding the glittery specialty stores--Neiman-Marcus, Bergdorf Goodman and Contempo Casuals--that gave the company much of its cachet.

Remaining will be five department store chains, led by the Broadway, that have historically been under-performers and that only recently have begun to benefit from a late-blooming push for improved customer service.

Some in the industry are dismayed at Hawley’s focus on department stores. Traditional department stores, they say, have lost the ability to keep up with faster-moving specialty stores and lack merchandising zest. Hawley disputes those notions, calling department stores “sleeping giants.”

The recent run-up in the company’s stock price--to a near-record level of $70--has defused some of the harsher criticism, but detractors still grumble.

“There’s an idea that they sold off the juicy assets to protect those department stores,” said Carol Farmer, a New York-based marketing consultant. “Everybody will be amazed if there’s enough oomph in the group he’s going to have to do anything with.”

If Hawley privately harbors such doubts, he does not let on. A workaholic who nevertheless finds time for jogging, swimming and even rare-book collecting, Hawley publicly insists--and family, close friends and associates maintain--that he is optimistic about department stores and feels little remorse about losing the specialty stores.

In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, Hawley noted, analysts accused the company of being on an “ego trip” for buying specialty stores when the future was supposedly in discounting. “We saw tremendous opportunity (in specialty stores),” Hawley said. “We feel that way now about department stores.”

Around the headquarters office, he and other employees are sporting small blue buttons emblazoned with “CHH on the move!”

But not long ago, many observers were quick to label the company a goner. Late last year when the Limited, a fast-growing specialty retailer based in Columbus, Ohio, made its second unfriendly takeover pass at Carter Hawley in 2 1/2 years, many on Wall Street figured Carter Hawley would succumb, given its stagnant stock price (around $40) and the Limited’s presumed fierce determination.

Little did Leslie H. Wexner, chairman of the Limited, or the investment community know what Philip Hawley had in store.

By the time Wexner re-entered the picture last November, Hawley’s plan to split Carter Hawley was already in motion. General Cinema, the movie theater operator and Pepsi bottler that had rescued the retailer from the Limited’s first takeover effort in 1984, liked the idea of running the specialty stores.

Midnight Phone Call

Wexner proposed a takeover in a midnight phone call to Hawley at the Plaza Hotel in New York on Nov. 24, the same night that General Cinema and Carter Hawley had reached agreement on the plan. It was “a very polite, cordial conversation,” Hawley said.

Such a chat might have unnerved some retailers, but Hawley simply fretted that the takeover threat “meant the whole process of thinking about the restructuring would become far more complicated than we had anticipated half an hour earlier.”

That the deal was proposed at the start of the crucial holiday season didn’t help. “When you ask a retailer when he would most like to be hit with a takeover bid, it would not be the Monday night before Thanksgiving,” Hawley quipped.

When the board chose to restructure instead, critics charged that management was entrenching itself. Hawley, however, contends that if Wexner “had put the right number on the table, he’d own the company.”

Some Wall Street observers dispute that a takeover ever would have been that simple. Pam Stubing, an analyst with Moody’s Investors Services in New York who has known Hawley for 11 years, said she told the Limited people after their bid failed: “I could have told you he would never let you have his company.”

Friends Come to Defense

Said one prominent Southern California businessman who is a friend of Hawley and asked to remain anonymous: “There’s a feeling that they really undid the company in defense of the company.”

To Hawley’s longtime friends and associates, those border on fighting words.

“The last thing in the world you would ever hear from Phil Hawley is, ‘Nobody’s going to get my company,’ ” said Donn B. Miller, a partner at the prominent Los Angeles law firm of O’Melveny & Myers and a Carter Hawley director since 1974. Hawley is proud of the emerging company, Miller said, and “he feels that it represents unique opportunities.”

Even so, Stanley Marcus, the legendary co-founder of Neiman-Marcus, suspects that Hawley gave up the specialty stores “with a great deal of reluctance.”

Somebody who had been captain of the Queen Elizabeth and “suddenly finds himself commander of a smaller ship may have mixed emotions,” said Marcus, who was unsuccessful in hiring Hawley in the 1950s. “This (the department store company) doesn’t have the glamour . . . but it’s a lot more fun because you can feel the engines.”

Throughout his career, Hawley has maintained a reputation for being cool in a crisis--and he has dealt with many. While his own company was fighting the takeover fires, he served on the boards of several other companies in turmoil: Bank of America and its parent, BankAmerica Corp., Atlantic Richfield and Walt Disney Co.

In the high-profile upheaval at Walt Disney in 1984, Hawley failed as a deal-maker when his candidate for chief executive lost out to Michael D. Eisner. Both Eisner and Hawley, who soon after resigned the board, maintain that they have no hard feelings about the episode and have, in fact, had dinner a couple of times.

“I don’t resent a man who does what he thinks is right,” Eisner says now.

Though formal and straitlaced in his business dealings, Hawley does have a lighter side. His 27-year-old son, Victor, the fifth of eight children, recalls that his father would often come home from the office and shoot baskets in his business suit on the driveway of their Hancock Park home.

Described by friends as an eternal optimist, Hawley would frequently inspire his children with the exhortation “pour the coals on.” There was always the expectation that the children would do their best, Victor said, even though Hawley and his wife, Mary, never imposed decisions (or curfews) on them.

Hawley briefly attended Stanford University before transferring to UC Berkeley to take part in a wartime Navy training program, getting his degree in 1946. In 1967, he completed Harvard’s advanced management program.

Among Hawley’s close associates and traveling companions are some of the best-known executives in America, but friends say he is foremost a family man. Victor Hawley doesn’t recall his father ever missing a child’s birthday or graduation.

He also stays in close touch with chums from his childhood in Portland, Ore., where he grew up in comfortable surroundings as the child of a paper mill operator.

Not given to great jocularity, Hawley nonetheless is fond of telling the family about the time he and a young friend used their slingshots to pelt a next-door neighbor’s freshly painted house with berries. Years later, that same neighbor persuaded Hawley to enter the retail business by going to work for Lipman Wolfe & Co., a carriage-trade store in Portland.

Before that, Hawley spent a brief time as an ice cream vendor in Portland, operating a store called, ironically, the Broadway Ice Cream Bowl. Alfred A. Aya Jr., his co-conspirator in the berry incident, said Hawley’s “superb” ice cream consistently won prizes at the Oregon state fair. Hawley also had “an extreme sense of integrity,” Aya said. “I remember a salesman coming in and telling him how he could save money by using artificial pecans. Phil nearly threw him out of the store.”

Busy Life Outside Work

Such anecdotes seldom pop up in business conversations with Hawley, who is downright uncomfortable discussing his personal life. “He’s not a guy who bares his soul,” said Richard J. Riordan, a wealthy Los Angeles lawyer and businessman.

Friends marvel at Hawley’s stamina and energy. He jogs about three miles a day, often capping that with a 20-lap swim before driving his 1983 platinum-colored Porsche 928S to the office about 7:30 a.m. In the course of planning the restructuring, Hawley traveled to London and Tokyo for one-day negotiations, seemingly untroubled by jet lag. (One longtime friend said he has never seen Hawley yawn.)

One friend describes Republican Hawley’s political leanings as “eclectic,” noting that he has backed such Democrats as Mayor Tom Bradley and Sen. Alan Cranston. “I always thought he ought to be a senator,” said Thornton F. Bradshaw, a former chairman of Arco and RCA and a close friend. Hawley quickly dismisses the idea: “It’s not something I want to do.”

Outside the company, Hawley is frequently called on to head fund drives or to sit on a diverse range of boards, from the Huntington Library to the Economist magazine to Catalyst, a women’s research organization. Catalyst’s president, Felice N. Schwartz, praises Hawley for promoting women and being “totally gender-blind.” Friends confide that Hawley is so busy that there is often a problem getting him to a meeting.

Miller, the Carter Hawley director and O’Melveny partner, said Hawley “does not regard himself as put upon by the level of activity that he sustains. He thrives on it.” On a hectic business trip to San Francisco, Miller was astounded when Hawley, an avid collector of books by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, showed up with a first-edition Sherlock Holmes. “You try to figure out when he got it and negotiated with the guy,” Miller said. “I can’t figure it out.”

Many times, the Hawleys have traveled with Bradshaw; Simon Ramo, the renowned scientist and engineer; R. Stanton Avery, Huntington board chairman, and their wives. On a cruise of the Greek islands in 1976, the four couples coined a term for themselves--Y Octada, from the Greek meaning “the eight.”

Hawley says he has made some of his most far-reaching decisions while on vacation. In the late 1970s, after several days of soul-searching in Newport Beach, he instituted a long-range strategy that would make the going rough for years to come.

By that time, Carter Hawley Hale had been on an acquisition binge, moving from a regional company to a loose confederation of specialty and department store chains nationwide. In late 1979, the company embarked on a costly master plan to improve customer service, cost controls, information systems and merchandising.

Well-Versed on Retailing

Hawley, who started as a buyer at the Broadway in 1958 and became chief executive in 1977, recognized the strategy was risky. As he told the board: “We’re going to have to bite a hole through our lip because our profits are going to go down and we won’t be well-understood.”

Raymond L. Watson, vice chairman of the Irvine Co. and former chairman of Walt Disney, recalls many conversations with Hawley about the troubles facing retailers.

“He realized that his job could not depend upon adding store after store anymore,” Watson said. “He had to turn that company around. He talked about the huge investment in computers . . . how Nordstrom was a big competitor. . . . He was very articulate about what was going on.”

As Hawley anticipated, earnings plunged even as the company was installing a $75-million computer center, opening its first corporate marketing-services department and beefing up the corporate staff. Weakened, Carter Hawley was ripe for a takeover bid by 1984.

Looking back, Hawley acknowledges two major mistakes from that period. The company didn’t explain its strategy--a “perfectly terrible decision” that Hawley said was made for competitive reasons--and it sorely misjudged how time-consuming and costly such fundamental changes would be. “If I could go back and replay the world,” Hawley said, “I would have been much more open and descriptive.”

One major objective of the current restructuring, Hawley said, is to allow management to focus on one business instead of two. In analysts’ view, one goal must be to infuse the department stores with more excitement.

Kurt Barnard, the New York-based publisher of an industry newsletter called Retail Marketing Report, noted “a history of disenchantment with stores operated by Carter Hawley . . . kind of a disregard for what contemporary customers are really after. . . . Department stores today are being outwitted, outsmarted every step of the way by specialty stores.”

Farmer, the New York consultant, concurred. On a recent visit to the new Broadway store at South Coast Plaza in Costa Mesa, a “grand piano was sitting there, which was a nice idea, but nobody was playing it,” she said. Meanwhile, across the way, Nordstrom’s piano player was in full swing. “They (Carter Hawley) pay a lot of lip service, but at the store level you don’t see a clear example of marketing,” she said.

Hawley--he describes himself as “not a great clothes buyer” who shops for apparel at Neiman-Marcus, the Broadway and “even at some stores we don’t own”--acknowledges that department stores in general must improve their merchandising and service. But he insists that the Broadway and Carter Hawley’s other chains have made great strides and are poised for progress.

Carter Hawley’s other chains are the Broadway-Southwest, based in Phoenix; Emporium Capwell in San Francisco; Weinstock’s in Sacramento, and Thalhimers in Richmond, Va.

Last week, the Broadway put on a two-day session at a downtown hotel designed to acquaint 1,300 sales associates from the chain’s 43 stores with fall apparel. From the reaction of employees who watched a glitzy, high-energy fashion show, the production appeared to have a desirable side effect as a much-needed morale-booster.

“They’re trying to get the employees more involved,” one participant said, “and that’s good.”

On Wall Street, analyst Stubing of Moody’s generally applauds the restructuring idea, but with a show-me attitude. “He (Hawley) has everything he wants,” she said. “He tells me that every one of his plans is now in place. Nothing is holding him back now. All he has to do is execute (the plan), and then he’ll make a believer of me.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.