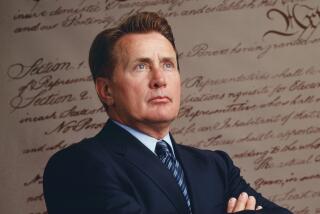

Coach Will Looks Over the New Talent : THE NEW SEASON A Spectator’s Guide to the 1988 Election<i> by George F. Will Simon & Schuster: $19.95; 192 pp.) </i>

You can almost hear the conversation between author and agent.

Agent: Ah, George, this ’88 thing. What do you say? Book?

George F. Will: Good idea. Let’s see, I can get ahead on my newspaper columns Monday. I’ve got TV tapings Tuesday and a lecture Wednesday. Yeah, I guess I could get it to you Friday.

And here it is.

From time to time, a journalist grows in influence along with a President and becomes identified with the era both shaped. Will is the celebrity journalist of the Reagan era.

Both are pleasantly likable men, glib, stylish, conservative. They share a talent for simultaneously being maddening and reassuring, firm and flexible, predictable and surprising--and they know how to play it on TV and in the papers.

And yes, both are overexposed and in danger of losing their influence.

What Will serves up under the misnomer “spectator’s guide” to the 1988 presidential campaign is a collection of notions culled from columns and commentaries, a helping of electoral demographics straight from the file cabinet, and a few Willisms all Cuisinarted together into four shapeless chapters: Reagan, Republicans, Democrats, Conclusions.

Guidebook? Hardly.

There is little here to guide us through the economic politics of the stock market’s historic plunge, little to help us decide if this is going to be an election of change or maintenance, or how to gauge the populist stirrings of the Christian right, or what to make of this tricky “character” business that has come to dominate the early pre-primary campaign season.

There’s nothing about the candidates and those contenders who refuse to become candidates.

Rather, Will promises background and perspective--those frequently forgotten antidotes to ignorance and fear.

Indeed he has entertainingly collected trenchant one-liners that help us grasp complicated events and make us more intelligent-sounding conversationalists. Suppose, for instance, you are asked about a massive voter registration drive being mounted by some special interest. Isn’t likely to matter, you can respond, quoting Will quoting journalist David Osborne: “New voters do not create new politics; new politics create new voters.”

And for such a small volume, Will still provides the necessary demographics to understand that beyond the faces and issues and travels and stumbles and recoveries of the unfolding campaign is a historical state-by-state electoral-vote mathematical trend that overwhelmingly favors Republicans.

Twenty-three states with 202 electoral votes have voted “N(2)FR(2)”--that is, Nixon twice, Ford once and Reagan twice. Only the District of Columbia with 3 electoral votes has shown the Democrats equal loyalty and voted “HMC(2)M”--that is, Humphrey, McGovern, Carter twice and Mondale. Of the remaining 333 electoral votes, Will writes, Democrats face the daunting task of winning four of five to win the White House.

To state the obvious, such arithmetic is terrific until some candidate finds a different formula. And almost surely someone will. If not this election, then the next or the next.

That leaves the remainder of the book for Will’s eccentric ideological meanderings about what might trigger a change in luck for Democrats or avoid it for Republicans. In newspaper columns or on TV, Will’s technique is to cleverly expose contradictions in someone else’s ideas or actions. But a book, even a short one, is too long to sustain Will without exposing his own.

He writes that Americans--forget all the hooey about hating big government--get just about as much government as they want. Even conservatives, he says, “have long since come to terms with the legitimacy of the public’s desire for a government energetic on behalf of their (sic)comfort, security and opportunity.”

Fewer than 50 pages away, Will has a Calvinistic change of heart as he baits liberals. He writes:”Because the Democratic Party has the loyalty of blacks, it must now get their attention with straight talk about the limited relevance of government action to the problems of the black underclass.”

Huh?

The reader might ask:What is the premise of this book?What is the purpose?

Here, there is seemingly no contradiction. Premise and purpose can be summed up in one word: Capitali$m.

If only Will had been more forthright and used the title:”The Old Season.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.