Identity Doubts Linger : Amerasians at Home in Philippines

OLONGAPO, Philippines — The wealthy, middle-aged Manila couple came to this U.S. military-base town on a recent morning for only one reason--to purchase the week-old illegitimate child of a Filipina bar girl.

As the prostitute cradled her infant, the wealthy couple asked her a battery of questions.

“Who was the father?” the woman began.

“I’m not sure, ma’am,” the prostitute replied, pausing often to think. “Maybe Italian. Maybe Australian. Or maybe, yes, I think sure, it was an American sailor.”

“An American?” the woman asked, her face brightening. “Think. Are you sure?”

‘From the Base’

“Yes, yes, an American,” the girl said, not even glancing down at the wriggling, emaciated baby. “Yes, I think I’m sure. An American from the base.”

The couple smiled. Yes, both thought, that would be fine.

The reason: “We want the child to look like us,” the prospective new mother said later. And, true enough, both of the adopting parents were themselves middle-aged Amerasians--living proof of how rich and how deep American blood remains in its former colony.

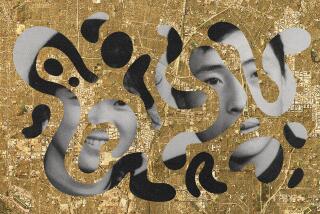

At a time when the word Amerasian is synonymous with discrimination and destitution throughout most of Southeast Asia, the Philippines stands alone as a nation where mixed-race children are not only welcomed but venerated.

Much of that sentiment is rooted in Philippine history--more than four centuries under white colonial rule. Thousands of mixed-race families, known here as mestizos, were born of native women and Spanish men, and thousands more began through intermarriages between Filipinos and Americans during the country’s five decades as a U.S. territory.

As a result of so long a tradition of racial mixing, an Amerasian in Philippine society today has, in many fields, an even better chance of success than full-blooded Filipinos.

The nation’s best-known basketball star--the most popular national sport here--is Amerasian. So are many of its top actors, politicians, singers and artists. Virtually every television commercial in Manila pictures mixed-blooded actors pitching products ranging from cigarettes and beer to cough syrup and baby powder.

Even foreign Amerasians are welcome. Thousands of Amerasian children from Vietnam are streaming into a refugee camp southwest of Manila this year to undergo a 6-month acculturation program before they are sent to America as new citizens.

Indeed, even the mayor of Olongapo, where the wealthy Amerasian couple met the bar girl and her child that morning, is Amerasian. And the negotiations for the child’s acquisition took place in the mayor’s living room.

“In many ways, it’s a hangover from the colonial experience,” said Olongapo Mayor Richard Gordon, whose Amerasian family name has become synonymous with the city after decades of unchallenged political control.

“We were taught to distrust each other under the Spanish. The Spaniards kept us divided and ruled by making everyone want to be like the Spaniards. Then came the Americans, and again, we wanted to be like them because they were in power.”

But for Gordon and thousands of other Amerasians in the Philippines--some, like Gordon, third-generation Amerasians--there are many disadvantages to their situation, even here. And it is for that reason, Gordon said, that he and his family, with no thought of profit, aid in the adoption of such children.

At the heart of the problem is an identity crisis that has left most Filipino Amerasians deeply confused--not only about the identities of their fathers, in the cases of children born in U.S. base towns, but in every case, about their own identities as well.

And that crisis has enormous legal dimensions in a country that still prizes free entry to the United States. Unless the Amerasian children here can prove conclusively that their fathers were indeed American, U.S. law will not allow them to claim American citizenship, a status prized far more than American bloodlines.

Baby-Selling Rackets

In addition, the great demand for Amerasian babies here--both by Filipino and American adopting parents--has combined with an inefficient and corrupt government adoption system to spawn baby-selling rackets in which the children’s roots are blurred still further.

What is more, half-black children often are as unwanted as half-whites are in demand. And when they can find no interested parents for such children, bar girls in Olongapo and Angeles City, the Philippines’ other U.S. base town, often abandon their children on doorsteps because they cannot afford to raise them.

But even then, such children are taken in by several centers where nuns and social workers raise them, finance their educations and help them fit profitably into a society where they are nonetheless still welcome.

There are more Amerasians in Olongapo than in any other Philippine town, and the town’s most popular doorsteps for abandoned Amerasians are, not surprisingly, those of Gordon and his mother, Amelia, a 69-year-old Filipina. Amelia Gordon married an Amerasian and has since single-handedly reared and found good jobs for more than 60 Amerasian orphans.

“When you talk about Amerasians in the Philippines, my mother is the story,” the mayor said.

An Issue in Bases’ Future

This year, though, the Amerasian story in Olongapo has taken on an added dimension, as negotiating teams from Manila and the United States prepare to begin talks next Tuesday on the future of the two sprawling U.S. bases here.

Critics of the bases charge that Filipino Amerasians are the most graphic symbols of how the American military presence continues to warp and pollute Filipino culture, while the bases’ supporters contend that the children are merely illustrations of the rich, warm and deeply shared ties between the two countries and cultures.

“There is no question that these children are the byproducts of the presence of the American base here,” Amelia Gordon said of the adjacent U.S. Subic Bay Naval Base, which has been an Olongapo institution since 1898 and is now home to 10,000 American servicemen. The local population of single American men swells by thousands more each time a U.S. naval group comes into port for shore liberty.

“We cannot avoid that mixing, because when the Americans first came here, the people were attracted to them. And, in many ways, that attraction continues even until today,” Amelia Gordon said.

Richard Juico is one of those “byproducts,” abandoned on Amelia Gordon’s front steps when he was three days old. That was 22 years ago.

Bible School Student

“It is true, from what I’ve read, that Amerasians are much better off here,” said Richard, an articulate, soft-spoken Bible school student who still lives with Gordon, along with 13 other Amerasian children she is raising.

“But for me, and most of the Amerasians that I talk to here, the main thing we are trying to solve is this identity crisis. To the Filipinos, I am a Filipino. To the Americans, I am an American. But, what am I to myself?”

Juico said he and his Amerasian friends--most of his friends are mixed race, he said--want to become U.S. citizens. But, under U.S. immigration law, they cannot because they cannot identify their fathers.

“I believe the Amerasians in the Philippines should at least have the right to choose their nationality,” he said. “Even if I go to the American Embassy, and it’s obvious enough by looking at me I have American blood in me, there’s nothing they can do. I have no identity, according to them.

More Opportunities

“If I had the choice, I would want to be an American citizen, because there are so many more opportunities for me there. Even the Vietnamese Amerasians have a choice now. But for us, there is no choice.”

For the city’s mayor, who views Richard Juico as something of a stepbrother, the situation was different. He did have a choice.

The Gordons, Olongapo’s first family for decades, trace their roots to a U.S. Army officer named John Jacob Gordon, who came to the Philippines soon after the archipelago was acquired from Spain in 1898. John Gordon married a Filipina and stayed, producing five sons. Among them was Gordon’s father, James, who became Olongapo’s first elected mayor and served until he was assassinated in office in the mid-1960s.

Richard Gordon, the present mayor, followed in his father’s footsteps. He was first elected in 1980, then fired by President Corazon Aquino after she assumed office in 1986. Finally, he was overwhelmingly reelected during local elections last January.

‘Decided to Be Filipino’

“My father was obviously an American, so I did have the choice,” Gordon said. “I got involved here, so I decided to be Filipino. But these kids don’t have the choice--and my question is, why should these kids be denied their birthright?

“The question is not whether they want to go to the States or not. The question is, do they have the choice? And, after all, isn’t the freedom of choice what the United States is all about?”

Gordon’s understanding of the problem is even more personal and intimate than his role as mayor would permit. Gordon’s wife, Kate, is also Amerasian, but she grew up not knowing who her father was. Only later in life did she learn that her father was a U.S. Navy sailor who had never even known she existed.

Seven years ago, the Gordons finally traced Kate’s father to a small town in Missouri. By then, Richard was already mayor and Kate, who is now Olongapo’s elected congresswoman in the Philippine House of Representatives, was a political figure in her own right.

“We called him (Kate’s father) on the phone and told him we obviously didn’t want anything out of him, just to meet him, and we did,” Gordon said.

But few of the Amerasians are as lucky, according to Sister Virginia Hachero, a Catholic nun who has been working with many of Olongapo’s 8,500 licensed bar girls--and an estimated 1,215 of their illegitimate Amerasian offspring--for the past decade.

Want to Know Fathers

“The problem of the Amerasian children is really that they want to know who is their father,” Sister Virginia said. “They want to meet their father. And they become rebellious when they don’t know who he is. They are jealous when they see other children like them with fathers.”

But the nun also concedes that, despite the emotional problem of identity, most of the Amerasian children of Olongapo end up leading successful lives.

Several of Sister Virginia’s Catholic-run centers in the city are financed in part by donations from American women’s groups at the adjacent Subic Bay Naval Base. Through them, scores of unwanted Amerasian children have been adopted by mixed-blood Filipino or American couples.

“It’s true, the Amerasian problem here is nothing like the other countries in the region,” Sister Virginia said. “For a long time, the mind of the Filipino has been conditioned that there is no difference between these Amerasians and anyone else. It is part of the colonial mentality. It is already fixed in our minds.

“Nowhere, I think, in the world are Amerasians so in demand as here in the Philippines.”

Sister Virginia has statistics to back up her assessment: In Olongapo’s church-run Pope John XXIII Community Center, which was established to care for bar girls’ children under 3 years old, there are no Amerasians.

“All the babies here now are Filipinos,” she said. “The Amerasians are too much in demand. They get adopted as soon as they come to us.

“In fact,” the sister added with a smile, “at the moment, we have a long waiting list.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.