1968’s Christmas Gift From Space: a New Look at Earth

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — Christmas Week 20 years ago was transformed into a magic and memorable occasion by three American astronauts who gave Earthlings a lasting gift of two vivid images from deep in space.

The first was a snapshot of one whole face of the Earth as never seen before, taken from 200,000 miles away. It made people realize for the first time that their planet was indeed a fragile entity, floating in a vast universe.

The second came on Christmas Eve when the astronauts of Apollo 8 read from the Old Testament Book of Genesis while transmitting breathtaking close-up pictures of the moon into living rooms of the world.

These were emotional events that raised the spirits of Americans who had suffered through a year that recorded the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., riots in major cities and at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and violent protests against the war in Vietnam.

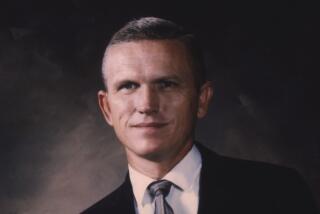

“You have bailed out 1968,” a friend telegraphed Apollo 8’s commander, Frank Borman.

Borman, James Lovell and William Anders lifted off at 7:51 a.m. on Dec. 21, 1968.

They checked the systems of their spacecraft for two orbits of the globe and were told by Mission Control in Houston, “Apollo 8, you are go for TLI”--”trans-lunar injection.”

Borman fired the still-attached Saturn rocket third stage and it sent them streaking upward at 24,196 m.p.h., heading for the moon, three days and 239,000 miles away.

The astronauts had embarked on man’s first visit to explore another world, the riskiest and deepest penetration yet into the void of his universe.

Apollo 8 was to circle the moon 10 times in 20 hours on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, gathering navigational, photographic and spacecraft performance data vitally needed before Americans could attempt to land on the moon in 1969.

The Christmas-time launch was a coincidence of orbital mechanics. The constantly moving moon is in position to receive visitors from Earth only three or four days each month.

The spacecraft performed perfectly. The men inside did not fare as well. All three experienced slight motion sickness, and Borman suffered insomnia and 24-hour intestinal flu. The next day they felt fine, and, looking out the window, they saw, for the first time, the Earth in its entirety, from 200,000 miles away.

Overwhelmed, they transmitted to the television screens of millions of homes this spectacular view of a gleaming marble-like sphere of blues and greens and browns and whites.

“You’re looking at yourself,” radioed Borman, acting as a tour guide.

“What you’re seeing is the Western Hemisphere. In the center, just lower to the center, is South America, all the way down to Cape Horn. I can see Baja California and the southwestern part of the United States.”

Lovell continued, describing royal-blue waters, bright white clouds and brownish land areas. “What I keep imagining is, if I’m some lonely traveler from another planet, what I’d think of the Earth at this altitude--whether I think it would be inhabited or not.”

Those television pictures had an overwhelming impact, giving humans a new perspective of their planet. Many felt more than ever that Earth was a beautiful planet, worth working to save. The picture of this lonely, delicate celestial body became a rallying point for environmentalists worldwide.

Minutes after the astronauts signed off the television show, Apollo 8 raced into the “equigravisphere,” a twilight zone where the gravitational pull of Earth and moon are equal. Then, less than 40,000 miles from the moon, Borman, Lovell and Anders did what no human had done before. They came under the prime influence of the moon’s gravity.

The spacecraft, its speed gradually falling during the outward journey, was traveling only 2,200 m.p.h. Early on Christmas Eve day, when Mission Control gave the go-ahead for lunar orbit, the moon’s gravity tug had accelerated the speed to 5,800 m.p.h., fast enough to swing the ship back toward Earth if a braking rocket failed to slow the craft to orbital speed.

The spacecraft moved around to the moon’s backside, cutting radio contact with ground control. For 36 agonizing minutes, the world waited. Was the engine firing a success? Not until the ship emerged around the moon’s edge was the answer known.

“We’ve got it!” shouted a voice in Mission Control amid a bedlam of cheers. “Apollo 8 is in lunar orbit!”

Lovell, the first to expound on the moon from only 70 miles distant, said, “It looks like plaster of Paris, a sort of grayish beach sand.” He had answered the first of many questions about that alien body that had awed humans since their beginning.

During the next 20 hours would come answers to many more. Throughout the day, the astronauts snapped thousands of photographs and motion pictures. In the first of two telecasts from lunar orbit, they relayed pictures of a wild and wondrous landscape pitted with massive craters.

‘Vast, Forbidding Place’

“It looks like a vast, lonely, forbidding place, an expanse of nothing

Lovell saw the distant Earth as “a grand oasis in the big vastness of space.”

The moon men surveyed and photographed all five of the prime sites being considered for the first Apollo manned landing mission. They practiced identifying and tracking lunar landmarks and discovered new ones. By evening, the astronauts were tired but so buoyed by their achievements that they expanded a telecast from a planned 15 minutes to 37 minutes.

While their camera scanned the lunar desert, blinding in the sunlight, forbidding in the shadow, and with an estimated half a billion people watching, some already celebrating Christmas, Anders said, “For all the people on Earth, the crew of Apollo 8 has a message we would like to send you.”

Silence fell over many households as, with the striking television pictures as a backdrop, Anders began reading the story of the creation from Genesis:

“In the beginning, God created the heaven and the Earth. And the Earth was without form, and void and darkness were upon the face of the deep. And the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, ‘Let there be light.’ And there was light. And God saw the light and it was good. And God divided the light from darkness.”

Lovell’s Reading

Lovell continued, “And God called the light day. And the darkness he called night. And the evening and the morning were the first day. And God said, ‘Let there be a firmament,’ and God made the firmament and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament. And it was so. And God called the firmament heaven. And the evening and the morning were the second day.”

From Borman: “And God said, ‘Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together into one place. And let the dry land appear.’ And it was so. And God called the dry land Earth. And the gathering together of the waters He called seas. And God saw that it was good.”

Then, the emotion of the day in his voice, Borman ended the telecast, saying: “And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a merry Christmas, and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.