W. Virginian in Mountain of Trouble : State Treasurer Faces Impeachment Trial on $297-Million Loss

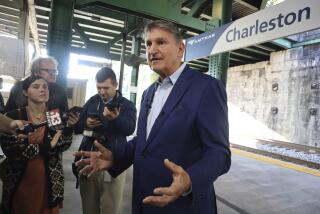

CHARLESTON, W.Va. — It was a busy weekday at the state Capitol here, and A. James Manchin--”state treasurer, loyal public servant and your everlasting friend,” as he frequently introduces himself--was in characteristic form.

“Each of you has the opportunity to become whatever you want in America and West Virginia,” he told a group of visiting eighth-graders.

“We have a truck driver right here from West Virginia who has driven over a million miles without an accident. . . . We have the best postmaster. . . . A lot of people who have been recognized throughout the world are from West Virginia.”

Then, ensuring that these embryonic voters never forget him, Manchin dug into the pockets of his dark, baggy suit and handed out a bright, new penny to each of the 42 students. “God bless you all!” he cried.

Most Popular Politician

With just such a combination of chauvinism and showmanship, Manchin, 62, has become the state’s most popular politician, receiving more votes than anybody on the state ballot in three of the last four elections. He styles himself as a man of the people, even having the words The People’s Office painted in big gold lettering on his office door. No first-time caller leaves without receiving a souvenir coin, trinket, medallion or certificate.

He was so popular that nobody held it against him that finances were not his strong suit, even though that was his job. “All those numbers look alike to me,” he has testified at legislative hearings.

But times are changing for both Jim Manchin and West Virginia.

Last January, an independent audit of state agencies uncovered a $297-million loss in the state investment fund that Manchin’s department manages. At the same time, the state, already one of the poorest in the nation, entered its worst debt crisis ever, with shortfalls in projected revenues expected to create $300 million in red ink this year and $300 million more next year.

So the Legislature took two painful steps. It imposed $380 million in new taxes, including a levy on food sales that hits the state’s many poor people hardest. And it impeached Jim Manchin, triggering a fight pitting Manchin and the traditional hill country politics of his state against the reformers that swept through other statehouses years ago.

Gaston Caperton, a reform-minded Charleston insurance executive making his first try for political office, won the governorship last November over former three-term Republican Gov. Arch Moore. He immediately convened a special session of the Legislature and pushed through, among other measures, a bill creating a state ethics commission and a proposal for government reorganization that would make the treasurer’s office an appointive position instead of elective.

Manchin “was fiddling while West Virginia was burning,” said Karen Trippett, a Charleston resident, echoing a widespread sentiment. “He’s history. He ought to be in the Smithsonian.”

The state Senate will try Manchin beginning July 10 on charges of poor management, improper investments and falsification of documents to cover up the shortfalls.

At a news conference in February, before the Legislature’s impeachment vote, he gathered his family around him and dramatically tore up a resignation letter, saying that he could not bear to have his grandchildren wondering “why ‘Paw-Paw’ quit in the middle of a fight.”

Manchin blames the financial losses on subordinates who directly handled the $3.5-billion investment fund and kept the shortfalls hidden from him and legislative auditors. “The system failed,” he said. “The checks didn’t check, the balances didn’t balance.”

He also points out that the losses occurred chiefly during a three-month span in early 1987. At virtually all other times, he maintains, the fund made many times more millions of dollars in interest income for the state, county and municipal agencies that participate in it.

But “there should not have been losses under any circumstances,” says state Delegate Marc Harman, a Republican from Petersburg in the northeastern part of the state who spearheaded the impeachment drive in the House. “Even under the absolutely worst-case scenario, the losses should have been minimal.”

Harman calls Manchin’s claims that he was a victim of his subordinates a “slap in the face” to voters. “If he didn’t know about the losses, he should have,” he said.

Franklin Cleckley, a West Virginia University law professor and Manchin’s attorney in the impeachment case, says that the treasurer’s chances for acquittal by the Senate would be good if the affair were not so highly politicized.

“But let’s face facts: $297 million is a lot to lose in a state that is almost bankrupt,” he added. “It’s a political issue . . . and Manchin is an easy target. He’s a totally independent politician whose constituency is merely the voters of West Virginia.”

Assailed in Press

News organizations have editorialized heavily against Manchin. The Charleston Gazette charged that “even before his office bungled away nearly $300 million of the people’s money, his endless self-aggrandizement at public expense was a constant violation of ethics.”

Pam Ramsey, state editor for United Press International, wrote in an opinion piece: “He’s wooed us with medallions and certificates, flowery speeches and bombastic attacks against those who dared to besmirch West Virginia’s good name. . . . We West Virginians must be a tolerant bunch, or perhaps just naive, to have listened to Manchin’s spiel this long without realizing or caring that it’s mostly hokum.”

Manchin says his life recently has been “pure hell.” Particularly galling to him, he says, are the critics who overlook his 40 years of service to the state in posts ranging from director of a junk car cleanup program (His slogan: “Purge our precious peaks of these jumbled jungles of junkery”) to state head of the Farmers Home Administration to West Virginia’s secretary of state.

He also was a state legislator in the late 1940s but was voted out of office after one two-year term because of his outspoken support for school desegregation.

Manchin takes encouragement, however, from the large number of citizens and voters who remain on his side. Cleckley says a poll shows West Virginia residents split about 50-50 over whether Manchin should be removed from office.

Staff writer Douglas Jehl contributed to this story from Washington

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.