STAGE REVIEW : ‘1789’: A Revolution on a Small Scale

If an American director who admired Peter Brook’s work set out to do his own version of Brook’s production of “The Mahabharata” at a small Los Angeles theater, one would wish him good luck, while entertaining some doubts about the project.

The same doubts attend Paul Verdier’s English-language premiere of Ariane Mnouchkine’s “1789” at the Las Palmas Theatre.

Verdier’s intentions are utterly honorable, and his production, within its limits, is not a disgrace. Moreover, the project has the blessing of Mnouchkine and her Theatre du Soleil. (Some of the original costumes are used.) There is no question of a rip-off here. This is a labor of love, if ever Los Angeles theater has seen one.

And it does give some sense of what the original 1970 production may have been like--particularly if the viewer can piece out his ignorance with memories of the Theatre du Soleil’s Shakespeare performances at the Olympic Arts Festival in 1984. The players putting on their whiteface makeup, the percussionists to the side, the combination of commedia dell’arte movement and stentorian language, the delicately worked costumes--we remember all that.

Apart from its value as a theatrical reconstruction, this “1789” does address a subject that almost no American theater (let alone Los Angeles theater) has had anything to say about during this bicentennial year: the French Revolution. And it says something interesting about it. “The people” lost the Revolution almost immediately to the people with money. Where most chronicles argue that the Revolution went too far, the suggestion here is that it didn’t go far enough: that there remains work to do.

All that admitted, “1789” is not comfortably sited at the Las Palmas Theatre, a small house made even smaller by the addition of playing spaces scattered around the theater. If there is anything clear about the performance style of the piece, it is that it was designed to project--to conquer a large space, such as the Theatre du Soleil’s theater on the outskirts of Paris, a converted bullet factory.

In a large space, the production’s physicality--the tumbling, the puppet shows, the booths, the processions, the long entrances and exits--was presumably thrilling, conveying both the majesty (and mock majesty) of royalty and the force of the mob.

Under a low ceiling, it makes for a cramped, in-your-face kind of evening--rather like trying to cram the Rose Parade onto the aisle of a bus. Verdier had originally conceived this as an outdoor production. It might have been wise to stick to that plan, even if the show did get rained out once or twice.

There is also the awareness that, deft as some of Verdier’s actors are (the production is bravely spoken and not clumsy on its feet), we are watching an imitation of a production designed for another time and place.

This isn’t to say the material examined here is irrelevant to America in ’89. Anything but. Take a walk down Hollywood Boulevard after the show and see the beggars. Verdier also splices in a telling image from the recent student uprisings in China, another example of a revolution devouring its young.

Stylistically, however, this “1789” has nothing to do with us. All the worse for us, perhaps. But mock commedia has no roots in the American experience. At the Las Palmas, we are watching a slide show from another culture, and not a very authoritative one. Verdier himself doesn’t know how “1789” worked with a live audience: He has only seen the film version.

The result has energy and intelligence, but it is apprentice-work next to the thing it is emulating. Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and this production is a painfully sincere homage to a great theater company. But in theater, perhaps it’s better that people do their own work.

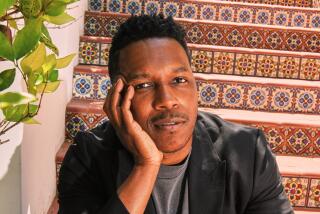

One actor in the company finds a way to make the play his business. His name is Hawthorne James. He reads the speeches of Marat with the bitterness of a revolutionary who once had pity for the privileged, but has drilled himself out of it. He would have graced the original company of “1789”--and even more, of its sequel, “1793.”

Plays at 1642 N. Las Palmas Ave., Hollywood, through Nov. 12. Performances Wednesdays-Saturdays at 8 p.m., Sundays at 7 p.m., with Saturday matinees at 2 p.m. Tickets $20-$24; (213) 465-1010.

‘1789’

An adaptation of Ariane Mnouchkine and the Theatre du Soleil’s epic of the French Revolution, presented by Stages Trilingual Theatre at the Las Palmas Theatre. Script Paul Verdier. Director Verdier. Setting John McCarthy. Costume coordinator Robert Prior. Puppets Christine Papalexis. Murals Casey Kramer and Chuck Caplinger. Music Gary Peterson. Production stage manager Jerry Charlson. Stage manager Karen Linick. With Steve Alden, Theresa Ambronn, Jean Louis Ayllon, Peter Barwe, David Duensing, Armando Duran, David Ellenstein, Rhys Greene, Marianne Halter, Carolyn Hennesy, Hawthorne James, Casey Kramer, John Lacques, Laura Lancaster, Laura Lustosa, Robert Mendelsohn, Christine Papalexis, Steven Ruggles, Jennifer Sims, Michael Tierney.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.