The Krenz Team: Second String to Hold the Old Hard Line : East Germany: New leadership, old ideology. The Politburo has changed names but the men in charge are heirs to a bankrupt regime.

RIDGEFIELD, Conn. — The Berlin Wall drama has barely begun. The opening of this massive prison gate ushers in a revolution with only one predictable outcome:more explosions to follow. Neither the present government nor its cast of characters can survive a new East Germany. Marchers in the streets have contributed a rousing first act. The ending is anyone’s guess, possibly anarchy.

I am a born Berliner and have been reporting on East Germany as an American writer since 1945--the year Germany and Berlin were carved up. Germans call that time Die Stunde Null, Zero Hour, when East Germany began. To research a book, I have been almost a commuter to my old home town for the last four years. And while no one wants to spoil the euphoric party mood triggered by the unexpectedly sudden collapse of the wall, some giddy fantasies have sprung up that need to be deflated.

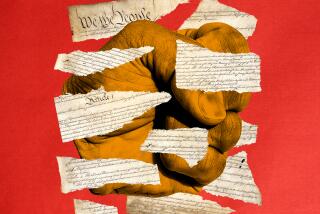

To welcome the apparently fresh crop of East Berlin leaders as “new faces,” much less “reformists,” is delusional. They are the second string of the old faces, the Erich Honeckers, the rigid apparatchiks for whom communism is a religion. These men are clones of their now-forgotten founding fathers--Wilhelm Pieck, Otto Grotewohl and Walter Ulbricht--who proved such unresponsive interview subjects in 1945.

Honecker is gone, his purge reportedly managed by Erich Mielke, once a convicted cop killer, then for decades head of the feared security police (Stasi). Mielke was himself fired shortly thereafter, yet if you check the biography of the “new” top man, Egon Krenz, you find a near-replica, step by step, of the rise of Honecker, the keeper of the wall.

Today’s bonzen --bosses--have sanitized themselves. They are younger than their predecessors. They no longer talk like uninterruptible tapes. They are more worldly. Some speak a little English. They are not as insensitive as Honecker, whose picture appeared in the national newspaper as many as 12 times in one day. And their dramatic ploy of uncorking the wall suggests, like the story about an old senator, that they may not have seen the light but felt the heat. No matter. We are seeing a stage set and the current team has just about admitted it.

The day the “new” Politburo was announced, No. 2 man Gunter Schabowski, told a cheering crowd: “If this Politburo proves unable to solve the problems, we are willing to step down again.” More stand-ins are available. Even the “new” prime minister, Hans Modrow, has admitted that his showmen may not be long for this world. “I can see the end coming,” he told a colleague.

Cynics rightly gag at headlines asking them to welcome freshly appointed ministers from “non-communist” parties. That is another charade. The old communist regime always nursed a cluster of acquiescent “competitive” parties. They carried different labels but had no principles of their own: “collaborators.” Conceivably, a desperate drive to save their jobs may turn a few of these old-timers into democrats of sorts. The rigidity of their political upbringing speaks against such a change of masks.

What about the “free elections” lately talked about? Perhaps popular pressure will turn this promise into reality. That would be a near-miracle. Communist regimes know ways of rigging elections that old Boss Ed Crump in Memphis only dreamed about. In 1946 I was briefly arrested along with a New York Times correspondent because she was freely taking pictures of the first “free” postwar elections in East Berlin. The memory lingers. So does communist know-how.

The prospect of a truly democratic alternative looks bleak. The courageous leaders of the street marchers have little name recognition, much less experience in organization or administration. They are a ragtag cadre of intellectuals, church people, artists and eccentrics. The opposition bubbles along in a leaderless vacuum, another ingredient for collapse and anarchy in the absence of the best and the brightest who have escaped--or are escaping daily--to the West.

If the westward drain continues, it may yet save the communists. A Cuban model may take hold. All remains calm in Havana because the opposition has left for Miami. East Germany may remain peaceful for the same reason.

Economics makes this unlikely. The communists’ Potemkin village built by toy money is tumbling down. Rents are still ridiculously low. The subway is still a nickel. Bread and milk cost next to nothing. But the subsidies that made these miracles possible have created a huge deficit, enormous foreign debt and an inflation rate of 12%--sores the leadership can no longer hide.

Such truths used to be state secrets. Indeed, secrecy was what kept East Germany quiet for so long. Even an operation as massive as the wall-building on Sunday, Aug. 13, 1961, could once be covered up as “exercises.” The word “wall” was taboo in the planning. Until 3 p.m. the Saturday before, not one telltale word was committed to typewriter; all preparations were oral or in handwritten drafts. Honecker’s “action staff” occupied just four rooms at police headquarters and did not become operational until 8 p.m. Saturday.

Such dark magic is easy in police states, yet even here the handwriting on the Berlin Wall goes back at least to Nov. 25, 1987, when a headline in the Wall Street Journal reported: “Germans are debating an unthinkable idea: removing the Berlin Wall.” In addition to quoting Germans, East and West, the article cited an Englishman, former foreign secretary David Owens, who even hit the timing--two years--correctly.

The urge for freedom went back longer and grew from a concatenation of causes:

* Mikhail S. Gorbachev, the indispensable engineer who set the climate controls for change throughout the East.

* An oppressive police state, producing revulsion against leather-coated secret police, dishonest media and a dictatorship that divided the country into the watchers and the watched.

* Communist schools. Parents among the refugees long told western researchers that they couldn’t stomach having their children indoctrinated.

* The travel urge. To Germans, travel means freedom.

* Shortages. Housewives were sick of standing in one line for carrots another line for potatoes and still another for rarely available half-rotten apples.

* Leadership arrogance. The privileges of the ruling elite were deeply resented in the supposedly “classless” society.

* Western television. TV images of Western freedom and opulence, beamed nightly into the East for decades, were enormously seductive.

* Monotony. The grayness of daily life, a numbing lack of stimulation.

* Outflow of refugees. The drain of doctors, bakers and skilled repairmen, along with so many of the young, totaled more than 4 million, one-fifth of a nation; cheerful reports from these resettlers to the folks back home in the East made the act of escape contagious.

“The wall must go!” became a cry fulfilled. But it is only Act One.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.