Ex-Resistance Fighter, Priest Who Rescues Paris Homeless Is Reluctant Media Star

PARIS — Abbe Pierre, a former resistance fighter who founded a chain of shelters for the homeless, has become a media star, albeit a reluctant one.

In the last month alone there have been a glossy film, a fat biography and an endless stream of magazine articles about the abbot, who has spent half a century plucking Europe’s poor and homeless from a life of despair on the streets.

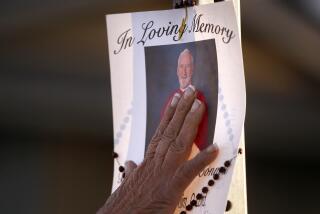

The frail priest, now 77, ranks among France’s five most popular men and was nominated for this year’s Nobel Peace Prize.

In his office in southwestern Paris he sits with his eyes half closed and his head bowed, tired after a hectic round of interviews and television appearances to promote the film.

“I have a little room in a Benedictine monastery to return to when all this is over,” he said against a background of church music.

“People recognize me everywhere. Sometimes taxi drivers refuse to let me pay,” he said in a voice so gentle that it is hard to hear. “It’s very humbling, when you know yourself and know how far you are from being what everyone admires.”

But a visit to a local movie theater is enough to get a sense of the anger that has fired him throughout his life, that has led him to beg on the streets and rifle garbage pails so that people will not go hungry.

His hostels, which he began in 1949, now span 32 countries and shelter 3,500 people in France alone.

The latest homage to his achievement is a star-studded feature film called “L’Hiver 54 (The Winter of ‘54),” currently playing to packed houses across the capital.

It narrates how he fought a single-handed battle against public apathy during the freezing winter of 1954, stirring the nation into helping thousands of homeless.

The story begins just after World War II, when a young priest named Henri Groues--Abbe Pierre was the name he used during his years fighting the Nazis in the Resistance--moved to a rambling, ramshackle house in a Paris suburb.

It quickly filled with students, visitors and the needy. Food and shelter were handed to anyone who knocked at the door. He called the center “Emmaus,” after the village where Christ appeared to disciples after the crucifixion.

He served as an independent member of Parliament from 1947 to 1953, but quit to dedicate himself completely to his work with the poor.

Dressed in a black cape and beret--still his daily uniform--Abbe Pierre roamed the streets at night, comforting those who huddled desperately against buildings’ warm air outlets. He knew many would die a few hours later, but his hostel was already packed.

On the night Parliament turned down his final appeal for money, a sobbing father burst into the priest’s study clutching the frozen body of his 3-month-old daughter.

That was the final straw. Abbe Pierre stormed into the local radio station and persuaded the producer to give him a few minutes of broadcast time. His emotional call for help, blankets and money drew an overwhelming response.

“We got 300,000 letters and 1 billion francs. Our movement created an extraordinary unanimity,” he said.

Lambert Wilson, a rising young star who plays the Abbe in the film, said the priest has had a profound influence on him.

“This role has really changed my life,” he told the Catholic monthly La Vie.

Meanwhile, in a quiet Paris suburb some 50 men carry on with their daily tasks in the original Emmaus hostel, collecting, repairing and reselling second-hand furniture to earn a living.

As for Abbe Pierre, they treat him exactly as he has always wanted to be treated despite his new celebrity status.

“I suppose we’re a bit like a family with a star in it,” said Dominique Jeanningros, head of the community. “We carry on seeing him in exactly the same way (as before).”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.