Korder Moves to Larger Themes With ‘Search’

M irkheim was here. Just like Kilroy. That seems to be the message, stripped bare, of Martin Mirkheim’s life. Except that he has a loftier vision than Kilroy. Mirkheim would rather make a movie than carve his name in a tree. And not just any movie, but one about victory against all odds.

“Martin is looking for something to distinguish himself, to leave his mark,” Howard Korder said of the Panglossian anti-hero of his new play, “Search and Destroy,” which is to receive its world premiere Friday at South Coast Repertory with Mark Harelik in the starring role.

“If we were speaking Yiddish, I would call Martin a luftmensch,” the 32-year-old playwright added in a recent interview at the theater. “It means a man of the air, a man with his head in the clouds, a man for whom the practicalities of the world don’t register.”

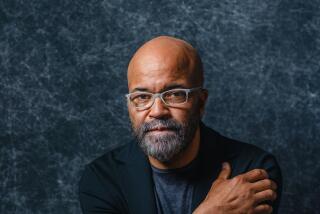

Korder himself gives the opposite impression. He seems a dreamer with his feet planted on the ground. Dark and thin, he is dressed in a brown turtleneck and black pants. He speaks carefully, despite an easy smile and quickness with a quip. Sometimes, apparently preferring to avoid even a suggestion of glibness, he rephrases his words because they flow too smoothly.

American history is replete with entrepreneurs in pursuit of success, Korder said, “men who have dreamed the biggest dreams and realized them and left the messy parts to others.” In Korder’s drama, Mirkheim, who longs to join that fraternity, seeks entrance by trying to escape--or, more accurately, to ignore--his limitations.

“He is,” Korder said, “a man with an idea. This is his delusion. But he is no more delusional than Henry Ford.”

“Search and Destroy” took root in Korder’s mind after he read about a murder case that evoked some of the most unsavory emblems of the ‘80s: rapacious greed, cocaine hunger and celebrity power. The case involved the 1983 killing of Roy Radin, a New York theatrical producer who had come to Los Angeles to break into the movie business.

Like Radin, whose demise became known as “The Cotton Club” murder because of its connection with the making of the 1984 movie, Mirkheim starts out as a promoter of circus-style acts who parlays his way into the entertainment mainstream through drug deals and worse. Yet Mirkheim’s fate differs significantly from Radin’s.

“The image of a man trying to burst his way into an arena of heavy hitters stuck with me,” Korder said. “But it was just a starting point. I’ve written a different story about a different man.”

In “Search and Destroy,” which is the Manhattan-born writer’s 11th play and the winner of a $50,000 production grant from “AT&T;: OnStage,” Korder traces Mirkheim’s bid for glory with a sardonic flair already evident in his two best-known works, “Boys’ Life” and “Lip Service.”

“Boys’ Life,” about a post-adolescent trio of desperate Lotharios, received a staged reading at SCR in 1985 and went on to a highly praised New York staging at Lincoln Center’s Mitzi E. Newhouse Theatre in 1988. A production drew mixed notices last year at the Los Angeles Theatre Center.

“Lip Service,” a spare two-hander about a failing TV talk show, first appeared Off-Broadway at Manhattan Punchline in 1985. Korder, who once worked as a story editor on CBS’s “Kate and Allie,” adapted the play for an HBO Showcase in 1988 under the producing aegis of David Mamet.

This time Korder has chosen a much larger canvas. “Search and Destroy” stretches from coast to coast through airports, jail cells and bus terminals; from the condos of Boca Raton, Fla., to the corporate lair of a Dallas-based “human potential” guru; from Minneapolis to Miami and from New Jersey to the dubious sanctuary of Hollywood.

“This play deals with the myth of America as a land of infinite possibility,” Korder said. “It is a myth that claims we have infinite resources, infinite opportunities and an infinitely perfectible future. Mirkheim believes the myth. He is a man whose head has been filled with the junk of our culture. He has grown up like a weed and flourished like a weed. His yearnings are universal.”

“I made a conscious decision when I started out as a writer,” Korder recalled, “that I would not write a play where lights come up on a living-room and people are sitting on a sofa, talking, and two hours later the lights come down.”

For drama that excites him, he looks to Jacobean playwrights like John Webster (“The White Devil,”) and Cyril Tourneur (“The Revenger’s Tragedy”) because of their social scope and their vigorous language. Chekhov also astonishes him. Not surprisingly, Korder mentions his admiration for the work of Beckett, Pinter and Mamet as well. Mamet’s influence on him has seemed so striking, in fact, that some critics pay Korder the back-handed compliment of describing his plays as “Mametesque.”

“There are worse people to be compared with,” he said, unfazed. “It’s better than being called Sidney Sheldon-like.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.