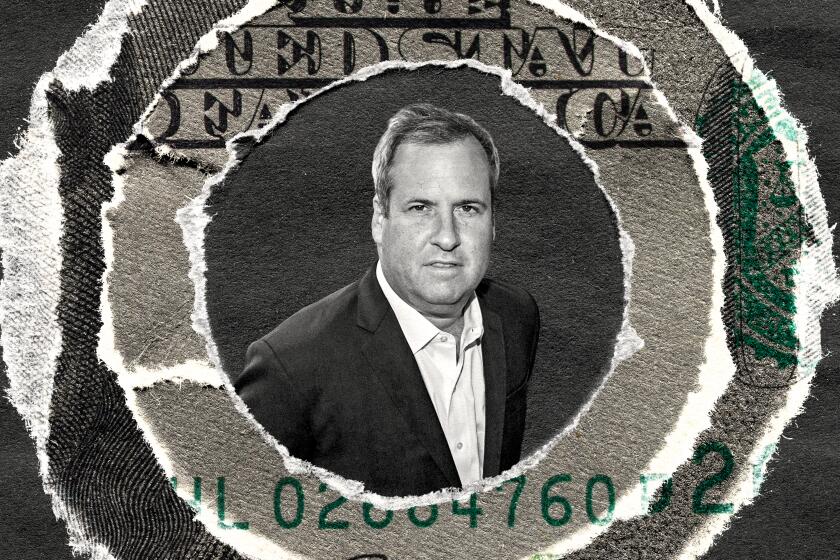

Insurance Veteran Getting Ready to Take His Second Company Public : Enterprise: By catering to small businesses, Joseph G. Havlick has been able to parlay two private workers’ compensation firms into millions of dollars.

By the late 1970s, Joseph G. Havlick, a 24-year veteran at Zenith National Insurance Corp. in Encino, a big workers’ compensation insurer, had risen to executive vice president. But when he got turned down for a promotion, Havlick quit and decided to do what he knew best. In 1977 he started his own workers’ compensation insurance firm.

That company was Fairmont Financial Inc., and despite some rough periods, the Burbank-based Fairmont prospered. And in 1987 the company was sold to financial giant Transamerica Corp. for $132 million of Transamerica stock. Havlick owned 5.7% of Fairmont when it was sold, so he received about $7.5 million of Transamerica stock. If he held onto it, Havlick made another good move, because Transamerica’s shares outperformed the stock market--as measured by Standard & Poor’s 500 index--in 1988 and 1989.

Havlick, 58, seems to like starting workers’ comp companies. In early 1988, a few months after he sold Fairmont, he started California Indemnity Insurance, another workers’ compensation insurer in Burbank. He launched the company by raising $7 million from investors in a private stock sale, and plans to raise an additional $16 million to $18 million by selling 33% of CII Financial Inc.--California Indemnity’s holding company--in its first public stock offering.

Because the offering is pending, Havlick declined to be interviewed. But a CII filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, outlining the proposed 1.5 million-share offering, said CII hopes to sell the stock for between $10.50 and $12 a share. CII also plans to use the cash to expand its business and pay off about $650,000 of bank debt.

The sale would dilute the CII stake owned by Havlick and his wife, Tanna P. Handley, a CII director, to about 15% from 21%. But it would value their 658,000 shares at between $6.9 million and $7.9 million. It means that since quitting his 9-to-5 job at Zenith, Havlick in salary and stock stands to earn more than $15 million by going into business for himself.

The SEC filing shows Havlick wooed several of his former Fairmont executives over to CII, and already has the company turning a profit. In the nine months that ended Sept. 30, CII, whose insurance is sold through independent agents, earned $1.8 million on revenue of $36.5 million.

CII nevertheless is a flyspeck competitor in California’s $7.5-billion workers’ compensation insurance market. Havlick’s former employer, Zenith, is 10 times bigger with revenue of $368 million in the first nine months of 1989, and Zenith Chairman Stanley R. Zax said he wasn’t familiar with Havlick or his firm. The market’s biggest player, the State Compensation Insurance Fund, a state-operated but self-supported agency, has annual revenue exceeding $2 billion.

When Havlick sold Fairmont, its annual revenue was $159 million and the company also operated in Texas and Colorado and offered surety bonds, leasing services and commercial printing. Transamerica, whose property and casualty insurance unit is based in Woodland Hills, declined comment on how Fairmont has performed since it bought the company.

Like Fairmont, CII focuses on selling insurance to small businesses, which to CII means those firms that pay $50,000 or less a year in premiums. CII, whose current customers pay an average of $9,000 in annual premiums, asserted in its SEC filing that the industry overall “does not aggressively solicit or adequately service” small businesses, enabling CII to exploit the niche.

Employers by law must provide insurance for workers injured on the job, and minimum rates and benefits of that insurance are, in effect, set by the state Department of Insurance. (Workers’ compensation insurance was not affected by Proposition 103, the controversial state initiative that is mainly aimed at cutting auto insurance rates.) But that does not mean all workers’ compensation insurers charge the same rate.

They try to undercut each other on price by offering rebates, known as “policyholder dividends,” to their customers at the end of each policy year. By law they can’t agree in advance to pay a certain dividend, but if an employer keeps its safety record high and workers’ compensation claims low, it can expect a fatter rebate.

Under Havlick’s reign, Fairmont was known for focusing on small businesses in part because they do not have the clout to demand big rebates on their workers’ compensation insurance, and so, are forced to pay relatively higher premiums because they must provide the insurance.

In the first nine months of 1989, CII paid $1.2 million of such rebates, or 3.4% of its “earned premiums.” Earned premiums, a gauge of an insurer’s underwriting revenue, are the amount of policyholders’ premiums that the insurer generally can keep without having to pay future claims from that money. In contrast, Zenith National’s policyholder dividends totaled 12.2% of its $137.5 million in earned premiums from workers’ compensation insurance over the same period. (Zenith also sells other property/casualty and life insurance.)

But there was nothing small about Havlick’s paychecks while he was at Fairmont. In 1984, he earned close to $500,000 a year in salary and bonuses, which at the time was more than twice the average pay for a chief executive of a California insurer of the same size, according to Heidrick & Struggles, an executive compensation consulting firm.

These days, however, Havlick’s corporate income from the fledgling CII is lower. His salary and bonuses last year totaled $176,000, but the company also picked up a $71,900 tab for his life insurance, car lease and other fringe benefits, the company’s SEC filing said.

While at Fairmont, Havlick also had a penchant for being surrounded by veteran executives--three of his executives there retired at age 70 or older. But at CII, he hired several of Fairmont’s younger managers, and CII’s chief financial officer, treasurer, general counsel and executive vice president are between 35 and 44 years old. Still, he claims CII’s executives have an average 21 years of experience each.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.