Fidel Castro: The Last <i> Caudillo </i> : The Challenge Is to Be Prepared When the End Comes

These are lonely days for Fidel Castro.

Cuba’s jefe maximo always fancied himself a special character on the world stage--a key actor not just in Latin America, where he was a symbol of revolutionary change, but also in the Soviet Bloc, for which he was an outpost near the U.S. mainland. But even Fidel’s friends have been wondering lately whether time has passed him by. The answer is yes. And events of the last few weeks only emphasize just how much of an anachronism Castro has become.

Start with the rapid collapse of the Soviet empire in Eastern Europe and the accelerating reform effort inside the Soviet Union itself. Castro was never a fan of Mikhail Gorbachev, or of perestroika. But as the Soviet leader consolidates his position in Moscow and former Warsaw Pact nations like Poland and Hungary go their own way, Fidel looks like the last Stalinist in the world.

His Latin American friends are in retreat, too. The Sandinistas have been voted out by the Nicaraguan people and must now learn to work as a real political party or be relegated to the dustbin of history. The guerrillas in El Salvador would end the long civil war there if they were given a chance to negotiate. And the toughest rebels in the Western Hemisphere, Peru’s Sendero Luminoso, say flatly that Castro’s a wimp.

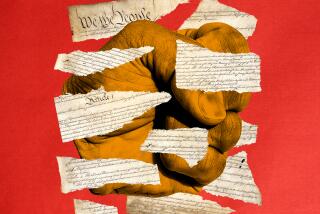

Fidel doesn’t even have anybody on the Latin American right to commiserate with: Chile’s Augusto Pinochet is out, so Castro has the dubious distinction of being the last old-style dictator in Latin America. For the man whose victory over Fulgencio Batista in 1959 was supposed to inspire revolutions throughout the region, being the last caudillo may be the cruelest irony of all.

Castro has been so much trouble for the U.S. government for so long--eight presidents have worried about him, with little to show for it--that some in Washington understandably might be tempted to gloat. But what U.S. policy-makers should be doing instead is planning to use the opportunity presented by Castro’s growing isolation to try and draw Cuba back into the American (in the broadest sense of that word) system.

The Soviet news media have begun criticizing Castro for refusing to join communism’s reform movement. That could presage a reduction of the $5 billion per year in Soviet aid Castro gets.If that aid ends, he’ll have to look for help elsewhere; and if his neighbors are ready to respond, they can demand that he behave himself in exchange.

But even if Castro refuses to face reality, he won’t live forever. There is no one to take his place, and once he’s gone, Cuba will change. By preparing now, the United States and the other democratic nations of the Americas can help ensure that the process is peaceful, like Czechoslovakia’s, rather than violent, like Romania’s.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.