Suspicions Fade as U.S., Soviets Enter New Era

WASHINGTON — The Washington summit, the first superpower meeting of the post-Cold War era, has seen relations between the United States and the Soviet Union begin a historic transformation--away from almost half a century of frozen enmity toward an active willingness to help each other.

The two countries still have major differences over several fundamental issues. But what has been new at this summit is how quickly the suspicions nurtured over 40 years of hostility have dissipated--and how clear it is that President Bush and Soviet President Mikhail S. Gorbachev have decided that mutual support is in their own self-interest.

“We are proceeding from the assumption that anything that is not good for the United States . . . will not be good for us either,” Gorbachev declared over and over in a startlingly blunt distillation of his new foreign policy.

“We’ve passed the stage of confrontation,” he said. “We are still in a period of rivalry, but the signs of partnership have appeared already.”

Bush echoed the Soviet president’s view. “Not long ago, some believed that the weight of history condemned our two great countries, our two great peoples, to permanent confrontation,” Bush said, as the two presidents announced 14 agreements ranging from nuclear arms to trade.

“Well, you and I must challenge history,” he said to Gorbachev, “. . . (and) build a relationship of lasting cooperation.”

These grand promises have already borne concrete results--with political payoffs for both presidents. Earlier this year, in response to American requests, Gorbachev helped Bush out of a jam in Central America by pressuring the leftist Sandinistas in Nicaragua to hold free elections.

Now, at the Washington summit, Bush has returned the favor. On Friday, he gave Gorbachev the benefit of the doubt by signing a trade agreement that the Soviet leader wanted--without waiting for all the concessions from Moscow that some U.S. conservatives demanded. A delighted Gorbachev said he appreciated the decision because it will help his efforts to launch “a dramatic change of direction in the Soviet economy, which is crucial for the future of perestroika ,” his reform program.

A constant undercurrent in Gorbachev’s flood of speeches to the American people--in ceremonies, at breakfast with members of Congress, in impromptu chats with reporters on the White House lawn--has been a plea for help in stabilizing his country.

“We should decide what is important for both sides,” he told the congressmen. “Does the Soviet Union need an unstable America? An America in turmoil? Or vice versa: Does the United States want a Soviet Union which is weak, torn by complexes and problems and turmoil, or do you want a dynamic Soviet state that is open to the outside world?”

That was as close as either Gorbachev or his American hosts came to openly voicing another new development at this summit: the first superpower meeting at which Soviet domestic politics was a major factor.

Bush responded as a good political ally should, praising Gorbachev elaborately and denying that Moscow’s domestic turmoil had made him any less formidable in negotiations.

And when another senior Administration official was asked whether the United States shouldn’t be cultivating likely successors to Gorbachev, such as Boris N. Yeltsin, the new president of the Russian republic, the official responded with a forceful: “No.” Gorbachev, he said, is the Administration’s man.

Even the nature of the disagreements between the two presidents was notable, officials said. While they disagreed sharply on significant issues--notably Lithuania’s demand for independence from the Soviet Union and a unified Germany’s place as a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization--they still kept those conflicts from getting in the way of other goals.

Indeed, on the Lithuanian issue it appeared that the two presidents simply “agreed to disagree.” White House Press Secretary Marlin Fitzwater said Saturday that Bush “made our case on Lithuania in the strongest and most direct fashion.” But despite what officials on both sides characterized as a blunt and even “passionate” exchange, U.S. officials seemed relatively pleased by Gorbachev’s assurances that he is serious about seeking peaceful negotiations with the Baltic republics.

The German issue was also handled with deft diplomacy: When Gorbachev and Bush realized on Thursday that they were too far apart on the question of NATO membership for the new German state, they simply kicked the problem back to their foreign ministers to deal with later. Gorbachev complained publicly that the U.S. position was “rather rigid,” but those were the harshest words spoken on either side on the issue.

On those questions and on arms control, the old superpower bellwether, the summit’s specific accomplishments have been unspectacular. If the meeting’s biggest test was to produce some forward motion on the question of German unification, it failed. In arms control, the two presidents agreed on most of the provisions of a strategic nuclear arms reduction treaty that they hope to sign later this year, but they failed to resolve any of the major remaining disagreements.

But more important than those specific “scorecard” items, U.S. and Soviet officials said, was their success on other less dramatic fronts in creating a new framework of understandings and obligations on both sides.

“While the Cold War might be characterized by the balance of terror, today I think U.S.-Soviet relations stand on the steadier ground of a balance of interests,” Secretary of State James A. Baker III said.

“And as we move forward, our job will be not so much to avoid war as to build a peace by searching creatively for the interests that we and the rest of the world have in common.”

In a sense, another U.S. official said, the United States and the Soviet Union are trying to establish “what you could call normal relations--the kind of relations we have with other countries.” Instead of summit meetings dominated by the demons of nuclear weaponry, he explained, the future of U.S.-Soviet relations should be in the less dramatic areas of trade, joint diplomatic action and cooperation to defuse possible conflicts in the Third World.

One early result is that the two presidents’ discussions of Third World issues, which once focused on conflicts in which they were on opposite sides--such as Afghanistan and Nicaragua--have begun turning to regions where the superpowers largely agree--India and Pakistan.

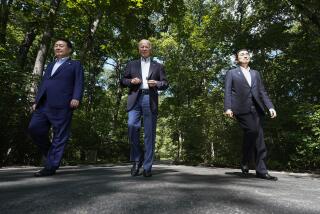

Another measure of the changing focus: Officials on both sides said Bush and Gorbachev had looked forward most to getting past their formal agenda and spending Saturday at Camp David, the President’s mountain retreat, to talk about the future.

Fitzwater said those talks were “an opportunity for them to just kind of lean back and reflect on how they might help.”

Several aides noted that Saturday at Camp David--a long, unhurried day in Maryland’s late spring sunshine--could not have been more unlike last December’s summit meeting at Malta, cut short when midwinter gales made it impossible for the superpowers’ leaders to leave their ships.

That wasn’t the only difference. At Malta, Gorbachev appeared as the triumphant leader of a reform movement that was sweeping the Communist world, and the onus was on Bush to demonstrate that he genuinely supported perestroika.

At Malta, it was a sign of great progress when the two leaders did something that had never been tried before: holding a joint news conference.

This time, the joint news conference had been scheduled from the start. And no one has raised the question of whether Bush’s support for perestroika is real.

“The turbulent developments of recent months after Malta have not led us astray from the goal we set together, so I believe that we have passed the first test,” Gorbachev said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.