Striving for Tocqueville’s America : Democracy: Campaign reforms may be needed, but reconnecting with one another and with the commonweal is more urgent.

Americans have taken justifiable satisfaction from this year’s triumphs of democracy worldwide. But before hastening to tutor others about self-government, we must reckon with Americans’ discontent with our own democracy--a “politics of irrelevance, of obscurantism,” in the words of Walter Mondale; a democracy in which “bull permeates everything,” according to Lee Atwater. Revitalizing our democracy should be at the top of our national agenda, but to make progress, we need to be clearer about what we strive for.

Our contemporary conception of democracy owes more than most observers recognize to the Austrian economic historian Joseph Schumpeter, who emigrated to this country in the 1930s. Impatient with idealistic theories about popular rule, Schumpeter defined democracy as merely “ . . . a competitive struggle for the people’s vote.” Think of political parties as firms competing for market share, he said, much as Cheerios and corn flakes vie for a place at our breakfast tables today. Think of politicians as merchandisers, a modern-day Schumpeter might say. Think of voters as manipulable consumers, uninformed about public issues, swayable through jingles and cartoons. Think of public policy, not as the outcome of a collective deliberation about the public interest, but as a byproduct of private interest, the mere residue of campaign strategy.

Schumpeter’s interpretation of modern democratic politics turned out to be remarkably prescient. He forecast, in effect, the central trend in American politics of the last half-century. When we talk now about democracy and its discontents, we focus almost entirely on political campaigns and marketing. We worry about sound bites and campaign spending. We lament “attack ads” and trivializing press coverage and low voter turnout. We propose public financing of campaigns and journalistic restraint. And this inside-the-Beltway debate about political reform follows Schumpeter’s lead by mindlessly assuming that the core of democracy is the electoral campaign.

But it need not be so. An even earlier European visitor to our shores, Alexis de Tocqueville, offered a quite different view of “democracy in America.” Tocqueville’s vision, admittedly rooted in the less urban, less frenetic America of the early 19th Century, highlighted the engagement of ordinary citizens in public affairs.

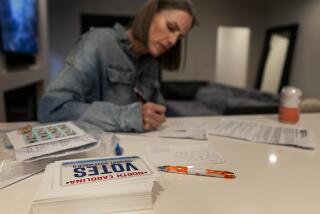

American democracy, according to Tocqueville, presumed a widely shared sense of social solidarity and civic obligation. The organizational sinews of our democracy were community associations, not electoral marketeers. Our democracy relied on our readiness to share responsibility for common problems. Democratic deliberation, a modern Tocqueville would say, rests on black churches and Rotary Clubs and Mothers Against Drunk Driving and Drop-a-Dime anti-drug crusades.

Democracy cannot be subcontracted to campaign strategists and focus groups. Responsible consideration of the “big” questions of our time--the twin deficits, the future of East-West relations, and so on--must grow from practical experience in civic discussions of dozens of local issues--school reform, homelessness, environmental abuses--in thousands of communities across the land. It is no accident that recent evidence suggests that the most effective means of combatting the plague of drugs is to engage the active participation of neighborhood groups.

If the paramount issue in American politics of the 1980s was making markets work better, the principal challenge of the 1990s will be to make democracy work better. A new era of practical reform is urgently needed. But lasting reform must begin at the grass roots, with Tocqueville’s robust vision rather than Schumpeter’s crass and shallow view. Our schools and universities, our civic, business and religious leaders, our press--and yes, even our politicians--must join in an effort to restore vigor to grass-roots organizations, to reconnect with one another and with the commonweal. Campaign reforms may be needed, but a reinvigorated emphasis on public engagement and civic solidarity is even more urgent.

The key to revitalizing American democracy rests not in the hands of the campaign strategist, or even the quavering candidate, but in our own. We must take responsibility for attacking our problems together, rather than just pointing angrily from the sidelines at those who fail to do it for us.

To the extent that the recent revolutions in Eastern Europe are grass-roots initiatives by millions of newly unfettered citizens, and that their elections are vehicles for debating basic political principles and philosophies, these new nations are closer to adopting Tocqueville’s vision of democracy than Schumpeter’s. And to that extent, we have something to learn about democracy from them, as well.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.