Appearances Can Be Deceiving When Sizing Up White’s Talent

It is mid July, Wally Joyner and Chili Davis are on the disabled list, the Angels are knocking on fifth place’s door and Devon White is in Edmonton, re-learning how to hit.

The situation is sad, on all fronts, in every sense of the word.

To replace Joyner, the Angels’ second-leading run-producer, the club recalls Edmonton first baseman Lee Stevens, who had yet to have a major league at-bat. To replace Davis, the Angels’ third-leading run-producer, the club recalls Edmonton catcher Ron Tingley, owner of a .149 career major league batting average.

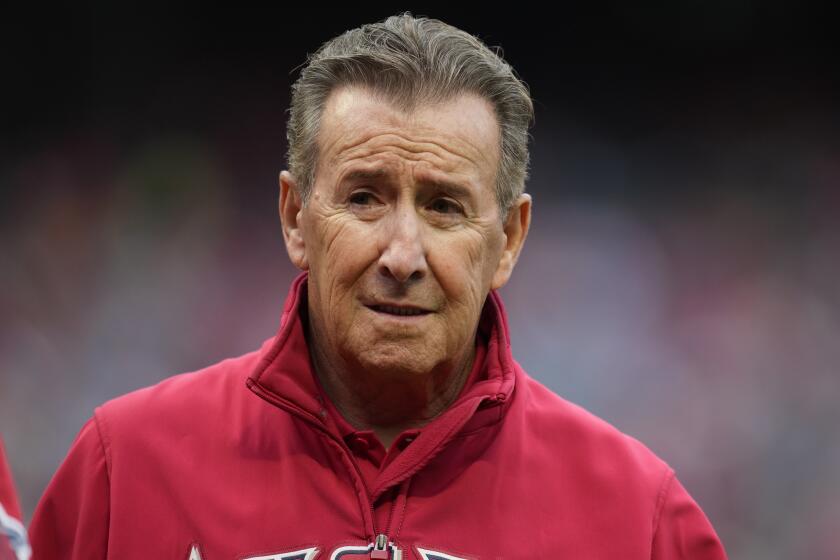

His old team is headed south, but White isn’t. The Angels need him but they don’t want him. Not now, not yet. White was sent north for a reason--remedial tutoring in Applied Woodwork 101--and classes have been in session for barely a week. Considering the stated course objective--”To recapture the consistency that can make him a great player,” Doug Rader says--this could take some time.

So White, one year removed from the American League All-Star team, remains in Edmonton, trapped. Trapped by circumstances, trapped by the wildest uppercut in the free world, trapped by four months of brilliance in the summer of 1987.

In a way, the best thing to happen to White was also the worst. In the first half of his first full big league season, White batted .293 with 17 home runs and 50 RBIs. By the end of July, he had 19 home runs and was closing in on 70 RBIs.

The numbers waylaid the Angels, who were expecting, maybe, a few stolen bases and a few doubles into the gap.

More crucially, the numbers also waylaid White.

Until then, White had the look of an unpolished Willie Wilson: line-drive hitter, limited punch, good speed. His minor league stats supported the comparison to the death. White hit seven, eight and 14 home runs during his last three seasons in the minors. Only once, when he split 74 RBIs between Midland and Edmonton in 1985, did he drive in as many as 70 runs.

Four months into the 1987 season, White began thinking he might be Eric Davis.

It was all fool’s gold. As we’ve since seen, everything about that 1987 season was a deceit. That was the Year of the Rabbit, when a little juice was surreptitiously added to the baseball and the game all but careened off a cliff.

A rookie hit 49 home runs. Even more amazingly, Wade Boggs hit 24. Joyner went from 22 home runs as 1986 rookie-of-the-year runner-up to 34--and didn’t make the All-Star team. The World Series was won by, of all people, the Minnesota Twins, a team that had two starting pitchers but also baseball’s burliest offense, let loose under the big top of a home park affectionately known as The Homerdome.

It’s a season that belongs in the dumpster, right next to strike-gutted 1981. Today, the artificially bloated power totals have no credibility, no meaning. The entire 162-game schedule, now just an aggravating blip on the grand statistical curve, should be fitted for an asterisk.

Examine the fallout:

Mark McGwire, the boy king of the 1987 sluggers, has become a reliable force in the middle of the lineup, but has yet to clear 33 home runs again. Boggs is Boggs again. Joyner has hit 37 home runs in nearly 400 games since the end of 1987. And the Twins? General Manager Andy MacPhail was apparently so embarrassed by the scam his team pulled on the sport that he has been trading the Twins back into their rightful place--fifth--ever since.

With White, the Angels can only hope the damage is not irreversible. But for a while, everyone involved was suckered. An Angel batting coach, Rick Down, proclaimed White to be the next Hank Aaron. White wanted to believe him, so he decided to look the part.

Forget that White has always lacked the innate strength of Aaron or Bo Jackson or even Ruben Sierra. He had to swing from the heels.

Forget that White is physically equipped to give the Angels precisely what they most need--a dynamic leadoff hitter. White chose to chase the dollar signs hanging beyond the outfield fences.

Forget that White’s 24 home runs in 1987 would translate into about 16 during a normal season. Once the switch was flicked on, White wasn’t about to turn back. He was born to go deep--or would be damned if he didn’t go down trying.

After 2 1/2 seasons of diminishing returns, White has returned to Edmonton. At best, the assignment is a midseason tuneup. At worst, it’s a remake of the Gary Pettis Story, where talented, young, Gold Glove-winning center fielder hits his way out of Anaheim, into Canada and, ultimately, onto another team’s roster.

Unfortunately, that was a subplot from 1987 that White either didn’t detect or respect. Now, he may be doomed to repeat it.

With Angel General Manager Mike Port finally awakening to the possibility that his team might need retooling--the view from Port’s Anaheim Stadium box must not be too good--another sad truth has surfaced. White, the man who could have brought Joe Carter or Ellis Burks to the Angels (with a bit of creative packaging) during the winter, now carries a surgeon general’s warning. White’s greatest resource, his potential, has been tainted, along with his market value.

If Port wishes to keep his pitching intact, he has little ammunition other than White if he’s truly intent on a shakeup. That leaves this choice: Deal White at cut-rate prices . . . or bite the bullet and pray the Edmonton experiment pans out.

Who’s to blame when situations degenerate?

Port, for waiting too long to make a move?

White, for waiting too long to try a course correction?

Or those Haitian seamstresses who added something extra to their product in 1987, helping create the grand Devon White illusion in the first place?

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.