Medication Can Be Bitter Pill : The Easley Case Is an Example of the Abuse of Over-The-Counter Products. The Danger Is That Such Abuse Can Have Unknowing Victims.

Filed away in the vast, sterile Rockville, Md., complex of the Food and Drug Administration are reams of physician reports on the effects of drugs. They are stored in cabinets or on computer disks.

These are the Form 1639s, Adverse Reaction Reports. They are perhaps the most detailed evidence available about the hazards of pharmaceuticals, from aspirin to zinc oxide.

One area is reserved for products that have ibuprofen, a painkiller categorized as a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). The analgesic can be found in such familiar pain relievers as Advil, Medipren, Motrin and Nuprin.

The reports under this category document side-effects of ibuprofen products, which command about 20% of the painkiller market.

But one of the most celebrated examples of alleged risks is not among the volumes in the FDA conservatory.

It is not an oversight. Physicians have enough paper to shuffle without recording every drug side-effect they encounter.

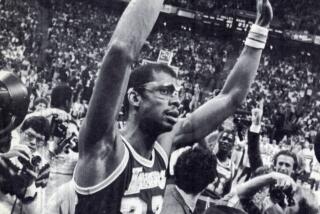

Still, the case of one-time Seattle Seahawk star Kenny Easley reminds consumers of the dangers of taking medications that become household products.

Easley was a five-time Pro Bowl safety for the Seahawks, and was once voted NFL defensive player of the year.

Today, his football career is over, the result of kidney failure he claims in a lawsuit began with taking four tablets of Advil to help reduce swelling in an injured ankle. He said he subsequently took from 16 to 20 tablets of Advil daily for at least three months before a doctor told him to stop.

Jon Borchardt, a retired Seahawk lineman, said players would take as much medication as necessary to numb their pain. He said the Seahawk training room has large dispensers or boxes of Advil, Tylenol and other nonprescription medications.

“They’re not even passed out, they’re just available,” Borchardt said.

Borchardt said the players were less concerned with warnings on labels than feeling good enough to play.

“Remember, there is tremendous pressure to win,” he said. “When you’re looking at a Kenny Easley, he is an integral part of winning. But to have an athlete’s health compromised is inexcusable.”

Although his kidney problems began sometime in 1986, Easley contends that he did not know of the seriousness of the disease until April 1988 when the Seahawks traded him to the Phoenix Cardinals. While administering a routine physical examination, Phoenix doctors discovered the kidney disorder.

In the complaint, Easley contends that Advil caused kidney deterioration, a claim that has some medical credibility.

The questions of who suggested Easley take so many tablets and how he was monitored once he took them will be central to the suit.

“We think it is a grievous example of a lack of professionalism on the part of the doctors and a fairly uncaring position by the drug manufacturer on disclosing what the potential side-effects are,” said Fred Zeder, Easley’s attorney.

Gerald Palm, a lawyer representing two of three doctors who are defendants, denied the charge.

“With regards to neglect, our defense in the matter is that the physicians never told Kenny to take 16 Advil a day or any Advil,” Palm said. “This is not a case of doctors failing to monitor him for something they told him to do.”

Easley has testified in one deposition that he quit taking Advil in September, but the defendants claim it was in July.

The doctors expected his condition to reverse itself when he stopped taking the drug, as research has shown usually happens.

Instead, Easley did not improve. He suffered from a condition called idiopathic nephrotic syndrome--unknown kidney failure.

“Our feeling is certainly this is tragic, but it is not anything the doctors did or failed to do,” Palm said. “We don’t think it had anything to do with Advil either.”

Perhaps the biggest issue is one that concerns every household--the safe use of Advil and other ibuprofen products.

The link between ibuprofen and kidney failure is inconclusive, an FDA doctor said. But the evidence is strong enough to worry some kidney specialists.

One of the latest studies at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions in Baltimore found that 25% of the patients suffered from acute kidney failure when taking ibuprofen. The condition was reversed when the patients stopped the drug use.

The 12 patients in the study all had pre-existing conditions that would lead to kidney failure with ibuprofen treatment, a fact that skews the study, the FDA’s John Harter said.

Another study at the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences showed that ibuprofen can cause kidney failure in individuals who have health problems, including high blood pressure, heart disease and pre-existing kidney problems.

The Advil label warns consumers not to take more than six tablets in a 24-hour period without consulting a physician.

As with most drugs, mega-doses can be hazardous. Ibuprofen interferes with the body’s production of prostaglandin, a hormone or hormone-like substance involved in inflammation.

As ibuprofen reduces the production of prostaglandin, it obstructs blood flow throughout the body.

For most people, this does not present a risk. But for those who already have reduced blood flow to the kidneys, such a factor could result in kidney failure.

William L. Henrich, a kidney specialist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas, has long advocated care in the blanket use of ibuprofen.

The drug was approved as an over-the-counter pain reliever six years ago. It still is prescribed by physicians in higher dosages. Ibuprofen is one of three nonprescription pain relievers. The others are aspirin and acetaminophen.

Harter, an FDA physician, said ibuprofen causes fewer gastrointestinal tract problems than aspirin. He said acetaminophen can be toxic to the liver.

“But the biggest advantage is that ibuprofen is much safer to have in your medicine chest if a 2-year-old gets into it and starts eating it,” he said. “It’s not as toxic on children.”

In 1985, Henrich led members of the National Kidney Foundation to protest dispensing of ibuprofen as a nonprescription drug without detailed warnings.

They recommended that the FDA alert consumers not to take the medication without physician supervision under certain conditions:

--Those allergic to aspirin.

--Those under a physician’s care for asthma or stomach problems.

--Those with heart disease, high blood pressure, liver disease or kidney disease.

--Those older than 65.

--Those using diuretics.

“We recognized that the risk of incurring kidney failure is low,” Henrich said. “But even a low incident rate translates into a fair number of people because so many are taking it.”

Henrich said the best way to safeguard against public misunderstanding was to have explicit warnings on each label. Others disagreed, claiming that too detailed a label would further confuse consumers.

The FDA adopted the second course of action.

Harter said when specific medical information was given in a test of labels, people made specific medical decisions that were incorrect.

“Anyone who takes mega-doses of a drug without realizing there is a potential risk when the label says don’t take more than six times a day . . . I don’t think we can protect the public against that sort of thing,” he said.

Henrich disagrees. He is concerned with the public perception that all over-the-counter medications are safe because they are federally approved. But he said as more powerful drugs become available, it becomes necessary for the buyer to understand labels.

“We’ve got an education problem,” he said. “I believe the public thinks because they can take this with impunity, they can take it with little risk--and that is a misconception.”

IBUPROFEN What it is and what it does

* The anti-inflammatory effect of ibuprofen helps reduce joint pain and stiffness.

* Ibuprofen is used in the treatment of headaches, menstrual pain, muscle pain and in certain arthritis cases.

* The analgesic can be purchased over-the-counter under product names such as Advil, Medipren, Motrin and Nuprin.

* A label on Advil boxes warns consumers not to take more than six tablets in a 24-hour period. It also warns not to take the drug for more than 10 consecutive days, and to consult a physician if problems occur.

* Common side-effects are abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea and heartburn, according to the American Medical Assn. Encyclopedia of Medicine.

* Studies show that excessive dosages of painkillers can cause kidney damage. But small dosages of ibuprofen might affect the kidneys in some people. The National Kidney Foundation identifies high-risk groups as those allergic to aspirin; those under a physician’s care for asthma or stomach problems; those with heart disease, high blood pressure, liver disease or kidney disease; those older than 65 and those using diuretics.

THE LAWSUIT AT A GLANCE * Easley’s attorneys filed suit in King County Superior Court in Seattle last year seeking unspecified damages for loss of income, medical costs and permanent disability. The suit is scheduled to be tried in the fall of 1991.

* Easley is suing the Seattle Seahawks, the team trainer, three physicians who treated him and Whitehall Laboratories, Inc., of New York. Whitehall is the distributor of Advil, a popular pain reliever that contains ibuprofen. Two of the doctors, Pierce Scranton and James Thrombold, are contracted by the Seahawks to handle team physical examinations and treat players.

* In a complaint, Easley alleges that his kidney trouble was the result of large dosages of Advil, which he claims he started using at the suggestion of Seahawk trainer James Whitesel after ankle surgery in March of 1986. Easley claims he was handed four tablets in the training room and told to take them any time his ankle bothered him. He said he took from 16 to 20 tablets from late April through July.

* Easley claims he was not informed in 1986 of his kidney problem, diagnosed as idopathic nephrotic syndrome, or unknown kidney failure.

* Easley contends in the complaint that he was given medical clearance to play through the 1987 season despite the condition.

* In separate answers to the complaint, the six defendants deny the allegations.

* Seahawk attorneys are confident the team will be dismissed as a defendant in a September summary meeting. They claim as an employer the Seahawks are not responsible for an employee’s health.

* An attorney representing Scranton, an orthopedist, and Thrombold, an internist, said the physicians never prescribed Advil for Easley. Gerald Palm, a Seattle lawyer, said the team physicians cleared Easley but did not know of his kidney problems because Easley barred them and the Seahawks from such knowledge.

* An attorney representing Dr. Gerald Pendras, who performed a biopsy on Easley’s kidneys in February of 1987, would not comment on the case. In the complaint, Pendras is accused of neglect for failing to advise Easley of potential kidney failure and clearing him to play during the 1987 season.

* Whitehall’s attorney, Kathy Cochran, said she has been instructed not to comment on the case. But Frank Woodside, a physician who practices medical law, said citing drug manufacturers in such cases is common and often invalid.