Murder Trial Looms as a ‘Whodunit’ of Odd Twists : Crime: Husband says a burglar killed his wife. Prosecutors allege that he did it to collect her insurance.

When Dan Montecalvo talks about the night of March 31, 1988, his Boston accent flattens and his voice slows as he gives his account of his wife’s murder:

Montecalvo had just returned from an evening stroll with his wife, Carol, when she entered their Glendale home alone. A moment later there was a startled shout and gunfire.

As Montecalvo rushed inside, he was seized from behind and shot in the back as the assailants fled. Later, he learned from his hospital bed that his 43-year-old wife had died of two gunshot wounds to the neck.

“I’ll never forget what happened that night,” Montecalvo said. “I worshiped that woman. She didn’t deserve to die like that, and I want her murderers caught.”

More than 2 1/2 years after her death, the trial of Carol Montecalvo’s accused killer will begin today in Pasadena’s Northeast Superior Court, and prosecutors say they have the man responsible: Dan Montecalvo.

“I’ve had some whodunits before but none as interesting as this one,” said prosecutor Robert Cohen. “It’s a difficult case, but in my own mind I think he did it, so we’re going to go forward and see if 12 (jurors) believe that way.”

Cohen is the first to admit that the case against the 49-year-old Montecalvo is circumstantial.

There was no eyewitness to the slaying, and no murder weapon has ever been found. But prosecutors portray Montecalvo as an ex-convict--knowledgeable about guns, saddled with gambling debts and desperate for money--who killed his wife to cash in on $600,000 in life insurance policies and collected more than half of it.

According to prosecutors, Montecalvo murdered his wife with a .38-caliber revolver shortly before 11 p.m., hours before the couple’s scheduled departure for a Hawaiian vacation. They allege that he then, in a chillingly calculated move, shot himself in the back with a .25-caliber handgun--hoping to inflict a minor wound and buttress his story that his wife’s killer was a panicked burglar.

Montecalvo and his attorney, however, scoff at that scenario.

They contend that investigators ignored possible suspects and focused exclusively on Montecalvo, then built a circumstantial case against him. They pointed to admitted discrepancies in police reports and disparities in the accounts of neighbors who heard the shooting.

“I’m not a saint, I know that,” Montecalvo said from the Los Angeles County Jail where he is being held without bail. “I’ve only known one saint in my life and that’s Carol. . . . I would never hurt her.”

Although it is only one of a litany of murder trials that fill the daily court calendars, the case already has some odd twists:

* Montecalvo filed a lawsuit last year accusing Burbank police officers of not responding quickly enough to save his wife’s life. The suit, Montecalvo contends, spurred police to pursue him as a murder suspect and arrest him earlier this year.

* The fingerprint of a department store salesman and recovering drug addict was found in a shaving lotion box in the Montecalvo home, and the salesman quit his job shortly after the murder and vanished. Montecalvo claims the police ignored the man as a possible suspect. Police said they now have ruled him out as the killer but would like to talk to him.

* Police waited for nearly two years to perform a key laboratory examination that prosecutors say indicates Montecalvo fired a gun the night of the killing. Montecalvo had passed an initial test for the presence of gunshot powder on his hands. Prosecutors said a test with a more sophisticated device turned up lead particles. Montecalvo disputes the accuracy of the new test.

* The original prosecutor on the case sought to dismiss the murder charge against Montecalvo. But top officials in the district attorney’s office overruled Deputy Dist. Atty. Penny Schneider and she relinquished her role.

Schneider declined to talk about the reason for her dismissal recommendation. But Larry Trapp, an assistant director in the district attorney’s Bureau of Branch and Area Operations, said: “We prosecute thousands and thousands of cases, and this is a relatively rare occasion. There was just a difference of opinion.

“In this particular case, when we looked at all the evidence, we believed that this case should go to trial and we believe there is enough evidence to convince the jury this man is guilty,” he added.

To some of his neighbors and fellow church members, Montecalvo has been targeted by law enforcement officials who seized on his troubled past--which includes two bank robbery convictions--and made him the convenient suspect in a case they could not solve.

“I personally feel in my own heart had he not been an ex-felon, this thing would have been done away with,” said Wil Strong, the pastor of Overcomers Church in Northridge, a nondenominational Christian church that included the Montecalvos as members.

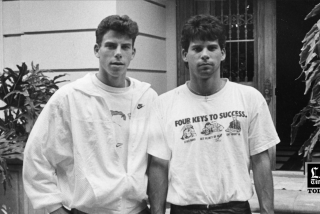

Carol Menon and Dan Montecalvo began their relationship in 1978 as prison pen pals, he told The Times. She was active in a Madison, Wis., ministry and he was in a prison cell in nearby Oxford serving time for bank robbery.

After six months of exchanging letters, Carol made her first visit to the prison. And on July 14, 1980, they were married in a prison chapel.

Three years later they moved to Southern California where Carol worked as an office manager and in advertising sales for local telephone companies.

“She loved you, and you knew that she loved you,” said Maree Flores, one of her closest friends. “There was a goodness in her that radiated. She loved the Lord and she loved people.”

Flores, who believes in Montecalvo’s innocence, said the couple had been looking forward to their Hawaiian vacation in 1988, a trip that Carol had won at her work.

That fateful evening, according to Montecalvo, after the couple had taken a walk, they had decided to replace an auto registration sticker that was scheduled to expire at midnight. Montecalvo said he waited in the driveway while Carol stepped into the house to get a towel to clean the license plate.

Whoever shot Carol Montecalvo fired the first bullet into the left side of her neck as she stood in the hallway, according to police reports. Her body--clad in a blue sweat suit, striped shirt and thongs--slumped to the floor.

Her assailant then apparently stepped toward her, held the gun inches from the back of her neck and fired a second bullet. To investigators, it was the executioner’s touch.

Still, the shots did not prove instantly fatal, and Dan Montecalvo insists that his wife could have survived if she had received prompt medical attention.

In his lawsuit, he claims that after Burbank police responded to his 911 call, the officers remained outside the house while emergency operators called him back twice to verify the shooting.

Despite his assurances that the intruders had fled, the police entered only when Montecalvo came out of the house, and paramedics were not called in until several minutes later, according to the 911 tape and police reports. To Montecalvo, the delay cost his wife any chance of survival. To police, their delayed entry was a standard precaution to avoid walking in on a gunman.

Montecalvo’s attorney now contends that it was his client’s outspoken criticism of the police and his subsequent lawsuit that intensified the investigation of him and turned him into the primary murder suspect.

“There were other possible suspects that the police ignored to focus on Dan,” Ronald Applegate said. “And they overlooked or botched evidence that would help his case.”

For example, he said, Montecalvo told police that one gunman may have had a mustache and a “Latin” accent, and he suggested the couple’s ex-gardeners as possible suspects. The gardeners, however, were not questioned until nearly two years later, Applegate said.

Police investigators said the gardeners now live in Mexico and were difficult to find.

Prosecutor Robert Cohen said Montecalvo came under growing scrutiny when it was learned that he had substantial gambling debts and his wife had hefty insurance policies.

Montecalvo confirmed that he gambled for a living but only because he found it difficult to find work because of his prison record and health problems. He managed a residential hotel in downtown Los Angeles until 1986, then went on disability with a bleeding ulcer.

Montecalvo said his wife also was aware of his gambling debts, including more than $40,000 he owed to Las Vegas casinos and a friend who had bankrolled his gambling. He said she also knew he had been repaying them. One former casino official told investigators that Montecalvo was on a repayment schedule but had been under pressure to speed up the payments.

Carol Montecalvo had a total of $600,000 in life insurance, most of it from present and past jobs. After her death, her husband said he collected about $340,000 before life insurance companies learned that he was the prime suspect and withheld payments.

The chief investigator, Burbank Detective Brian Arnspiger, said it is the image of the murder victim that has kept him digging for evidence against Montecalvo.

“Carol has kept me awake ever since I got this case,” he said. “Every night I wake up and make notes to myself . . . and I’m convinced he did it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.