PRIVATE LIVES, PUBLIC PLACES : For the Smallest of Life’s Victims, a Hero of Healing Goes ‘Home’

In the land of the continuous present, it is hard sometimes to hold on to who we once were, to hold on to friends and the old neighborhood. We move up, move on and turn away our faces from earlier, harder days. It brings riches but it makes for a calloused heart.

Some men, though, manage it all: The past and the present to them are one. Columbus McAlpin is such a man.

McAlpin grew up behind a store on Central Avenue; he was there as Watts crumbled, he lived through its burning. When he was recruited to play football for UCLA, he turned down the scholarship. Those were difficult times for his family and he needed to work full time. Football, to him, was a luxury. He studied, he cleaned houses, loaded trucks and talks now only of the “riches” of his early years, of his family’s support. But he knew hard, hard days--in those times, a penniless black man needed a giant’s heart to go through medical school.

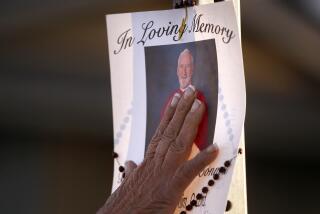

Dr. Columbus McAlpin is a distinguished surgeon. At 47, his large, strong face has a touch of pallor; there is white in his grizzled beard. His tired eyes hold sorrow and tenderness, and those who don’t look hard enough are deceived by the warm, unhurried ease and by the elegance. They assume he was born to the soft-carpeted suites, to the hushed respect of his private practice at Santa Monica and Cedars-Sinai.

The irony is that his father had the same polish, the same dignity. He came to Los Angeles from Louisiana, poor and a carpenter, looking to shipbuilding to put food on his table, to support six children. But he was a schoolteacher by trade--a boy who had picked cotton in the fields and was 21 before he entered high school. He graduated college with the highest honors in its history; imagine what achievements he might have known. Columbus McAlpin is right: he is not self-made. He inherited intelligence, endurance and a lion’s courage.

And all of this explains in some way why, seven days a week, 24 hours a day, he is still on call at the Martin Luther King Hospital in Watts. “These are my kids,” he says with a shrug, “these are my people.” In his overcrowded Thursday clinic, he rushes from cubicle to cubicle, sometimes reeling with tiredness, finding time to hold children, to protect mothers, to teach, to explain and to draw comfort from those who have worked together for years.

Children born with pieces missing, with a piece diseased, patients touched by the miracle of one man’s hands, reworking tiny, frail bodies, restitching, watching over, giving back life to those who, 20, even 10 years ago, would have died. Fathers without English, without papers, sheltering small sons with their bodies as if to save them pain. Mothers with many children, stoic in their fear, hearing the word cancer where it was never spoken. A brave young boy, born without an anus, betraying not a scrap of anger or bitterness toward the humiliation and the pain of having his body rebuilt.

How is one man able to show such kindness to everyone? Humble, gentle, apologetic as he hurts, full of shy delight at a small girl’s smile, at tears clearing--he has not one scrap of self-satisfaction. “I operated on a little boy two weeks ago,” he says, “who had a special kind of cancer with no known cure. And that kid was just as pleasant as he could be. Now, if he could do that, why can’t we?”

He takes the rich who pay, the successful who are insured, those who never think to count the cost; he takes the homeless and indigent--children who are sick, some who die as he operates, others who die later.

He is married; his wife is a dentist and there is a small daughter, left at home before dawn and sometimes not seen again until midnight.

So in the age of doctors who are professional corporations, who are busy taking calls from the desert, it is well to remember that there are also among us old-fashioned healers who work too hard and care too much.