TV AND THE GULF WAR : Networks Learn the Lessons of War : Television: News executives say they have become more cautious in airing reports. But they also bemoan what they call a lack of information from the Pentagon.

Network television executives said Wednesday that they have learned important lessons from the first week of the Persian Gulf War and the impact of its dramatic, often-controversial, live-by-satellite coverage.

Despite heroic performances in the field and interference from censors, American television has been criticized for fragmentary, sometimes-undocumented, nerve-shattering reports and a lack of depth in dealing with the immediacy of the first true video war.

“One thing we have learned is that an air raid siren does not necessarily mean a missile anymore,” said Joanna Bistany, ABC News vice president. “We are more cautious in getting the guidance of our people in the field before we go on with a special report now, because we went on when the air raid signals went off in Israel and it was a false alarm.

“Initially, in the frenzy, we were covering everything because it was changing and happening so quickly. We’re more sophisticated about it. There is also the matter of remaining calm on the air. We realized how important that is to the people watching.”

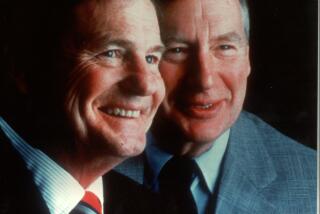

“The U.S. military has so far pretty well buttoned up this story,” said Ed Turner, executive vice president of Cable News Network. But he thought that Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney and Gen. Colin L. Powell, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, “were more forthcoming” in their Wednesday briefing that was broadcast live by ABC, CBS, NBC and CNN.

“They read newspapers and watch television and read statements that we simply don’t know what’s going on. It’s in their interest to have an informed public.”

Turner acknowledged that CNN was vulnerable to criticism of fragmentary reporting because of its all-news, 24-hour format. “We have addressed some very vexing moral as well as journalistic issues, created by our ability to go live from the hot spots.

“Therefore,” said Turner, “we have developed a format that tries to recap in some kind of lucid fashion each hour what we know as of now.”

CNN also added a new, fuller dimension to its rapid-fire coverage this week with commentaries by Bill Moyers.

“What we have learned is that there are no easy answers to the problems of national security and our desire to report the story,” Turner said. “Those briefings in Riyadh are a joke. But you keep trying. You can’t pack up your tripod and go home.”

A spokesman for CBS News said that “the biggest lesson is clearly that Pentagon guidelines are seriously hampering every effort by journalists to report the war. It’s our feeling that they go too far.”

The spokesman, Tom Goodman, added: “If it’s a matter of military and national security, no problem. But it touches on censorship. We’re stuck in political situations where you’re taken on tours and find that expenses often are spent on non-news stories. You’ll find out how maintenance is preparing and the mood of the troops, but you won’t get a report on how the war is going.

“If you’re watching TV and listening, you’re saying these guys don’t know the facts. We feel the public is being ill-served. If the ground war that everyone expects erupts, the feeling is that censorship will be extreme.”

David Miller, director of foreign news for NBC and former Saigon bureau chief during the Vietnam War, said the “immediacy” in the coverage of the gulf conflict is “overwhelming. You can point a camera at the sky and see a weapon being hit by a defensive rocket.

“What the Administration can’t handle,” Miller added, “is the fact that these Scuds, which may not be doing much damage militarily, are bringing home to the American people the terror of war.”

Miller agreed that “what you’re seeing is the fragments of stories--episodic, passing events.” But he said reporters must do their job nonetheless: “War is messy, war is chaotic, war is disorderly. You can’t worry about what critics say. It’s when we become intellectuals that we drown. That’s for other people.”

One of television’s major surprises during the Gulf War has been the heavy coverage by PBS, suddenly aggressive under its new program boss, Jennifer Lawson. There have been extended hours of the “MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour” and numerous special reports.

“We learned that public television can be responsive to breaking events,” said John Grant, PBS vice president of scheduling and administration. “This is unprecedented in public TV history. Other networks refined what they do. We learned that we could do it.”

Added Grant: “We also learned that stations wanted us to do it. And viewers wanted it. We knew that because even before war broke out, the ratings for our coverage of the House and Senate debates on the war were very encouraging--up 40% from normal.

“For the first time in our history now, we’ve done weekend editions of MacNeil/Lehrer. We had stated that public TV had to be more timely, and the crisis in the Gulf accelerated our movement.”

Also coming further into its own during the Gulf War has been C-SPAN, with the voices of Americans being heard in lengthy, daily phone-in programs. Once known mainly for its coverage of Congress and other governmental agencies, C-SPAN has re-run major briefings in prime time and even has a three-person crew in Saudi Arabia covering the media coverage as well as the war.

“We thought the best thing we could do is just let people talk,” said C-SPAN founder and anchor Brian Lamb. “We counted 1,600 calls the first seven days. I sensed that people had a real need to say something out loud. The euphoria of the first day transformed into a real fear you hear from callers.”

A C-SPAN spokeswoman said the channel thinks its coverage of the media is important “because of media influence in the type of information the public gets. To be truly informed, you must know about the source.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.