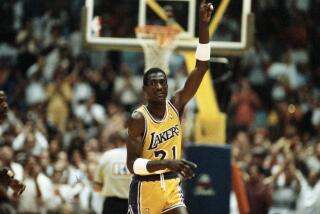

MAGIC JOHNSON’S : Role Model : Laker Follows in the Footsteps of Robertson, With Assist Record Bonding Their Unique Abilities

It seems appropriate that the Lakers’ Magic Johnson is the man who broke Oscar Robertson’s NBA record for assists.

Like Robertson, Johnson, 31, who had 19 assists Monday night to give him 9,898 and break the record of 9,887, is not your everyday point guard. Bob Cousy answered that description. John Stockton does today--little guys at 6 feet 1 and 175. Robertson was 6-5 and 215, and Johnson is 6-9 and 220.

Cousy was the prototype playmaker with the Boston Celtics from 1950-63. He handled the ball with a flair that set him apart from not only his contemporaries, but about anyone else. He would pass, dribble or transfer the ball behind his back, and he wouldn’t do it simply to be a showboat.

Although he ranks only sixth on the assist list with 6,955, Cousy holds the record of eight assist titles and he won them in consecutive years from 1953 through 1960.

Stockton, 29, the pass master of the Utah Jazz, is Cousy’s modern counterpart. Stockton has led the league in assists the past three seasons, with Johnson finishing second each time, and is leading again this season, with Johnson again second. Stockton isn’t as fancy as Cousy was, but he fits perfectly into the pattern that Cousy set.

Why have bigger players such as Robertson and Johnson set assist records?

Cousy said recently that Robertson “wasn’t a classic point guard,” and the same probably applies to Johnson, although he handles the ball as well as Stockton, Isiah Thomas or any other 6-1 floor general.

Whereas Robertson relied on strength, instinct and savvy, Johnson is quicker and flashier and without peer on the fast break.

Both were/are complete basketball players, not merely men who performed given roles. Shooting, rebounding, passing, leadership--few have put together a comparable package.

Consider:

Robertson averaged a triple-double for an entire season and missed three other times by a fraction of a rebound or an assist. In 1961-62, he averaged 30.8 points, 12.5 rebounds and 11.3 assists. For his career, from 1960-74, he averaged 25.7 points, 7.5 rebounds and 9.5 assists.

Johnson has yet to match that, but he has had 13 triple-doubles this season and is averaging 20 points, seven rebounds and 12.6 assists.

For his career, Johnson has averaged 11.2 assists to Robertson’s 9.5. Johnson needed only 871 games to accomplish what Robertson did in 1,040.

However, shooting accuracy has increased markedly over the years, making assists more easily attainable than in Robertson’s era. Thirty seasons ago, when Robertson was a rookie, team shooting averages ranged from .386 to .419. This season, the range is .441 to .513.

Nate Archibald of the Kansas City-Omaha (now Sacramento) Kings is the only player to lead the league in scoring and assists in the same season. Jerry West of the Lakers, now their general manager, also won titles in both categories, but in different seasons.

Robertson ranks second to Cousy in assist titles with six. He finished second and third twice each, and Cousy was second once, third three times and fourth once. Assuming that Johnson holds his position through the three remaining regular-season games this week, he will have six seconds to go with his four firsts in 12 seasons.

Kevin Porter also led the league in assists four times. Lenny Wilkens, now coach of the Cleveland Cavaliers, did it twice, as did Guy Rodgers and Andy Phillip.

West is not the only former Laker who did it once. The other is Wilt Chamberlain.

Before the 1967-68 season, Chamberlain, then with the Philadelphia 76ers, vowed to prove himself an all-around player. He had been a perennial leader in scoring, rebounding and field-goal percentage, but some had called him a selfish player. He answered the critics by leading the league in assists--and in rebounds and field-goal percentage. He dropped to third place in scoring, but made his point and never reached the top 10 in assists again.

The Robertson-Johnson connection extends to a personal relationship that dates to Johnson’s days at Michigan State.

Johnson said recently that Robertson had been his idol since boyhood. He also said he had “stolen” a few things from Robertson’s game, and that is clear to those who remember his style.

Johnson is a master at backing toward the basket. Robertson’s theory on the back-in was never to take a shot if he could move a foot or so closer to the basket.

Johnson tries to get all of his teammates involved in the early going, then--if necessary--takes over the game down the stretch.

Robertson, 52, talked about it in a conference call last week from Cincinnati, where he owns a chemical company and a corrugated box company.

“I always felt that the first thing I had to do was probe,” he said. “I tried to find out if plays that worked the last time would work this time. I tried to find out which of my teammates had a hot hand, and how the defense would react to what we were doing. All these things went through my mind, and once I got answers, our game plan was set.”

Asked if he saw himself in Johnson, Robertson said: “I don’t know. Everybody plays his own way. I do know Magic does such a terrific job that it’s unbelievable.

“Everyone said I was too slow and too big to play in the backcourt, but 14 years in the league wasn’t too bad. You just need deceptive speed to do the job. Magic has great speed.”

West, also 52, sees “no similarity whatsoever” between the styles of Robertson and Johnson.

“They’re completely opposite,” West said. “Oscar was a great, great, great, great player--period. He could do everything. Magic is a different kind of player, but he’s also a great, great, great player.”

Asked to compare his style with Robertson’s, West said: “I don’t dwell in the past. I did something that was fun for me to do, but I could care less about it now.”

Robertson said it “was nice to hear” that Johnson had called him his idol.

Not so nice to hear, Robertson said, was Cousy’s remark that he wasn’t a classic point guard.

Actually, Cousy meant it as a compliment, adding that Robertson “was the forerunner of the strong 6-5 guards who overpower you.”

Still, Robertson bristled when word of Cousy’s comment was relayed.

“What is a classic point guard?” Oscar asked. “Marques Haynes was the world’s greatest dribbler, and all the Globetrotters made fancy passes. I could do all these things, but playing basketball is a simple matter of getting the job done.

“If being a classic point guard means passing behind your back and flipping the ball over your head, OK. I had situations where I flipped it behind my head, so what’s the big deal? Bob (Cousy) has his opinion. Everybody has his opinion.”

Robertson singled out Cousy as the player who set the standard.

“There’s no doubt about that,” Robertson said. “Bob didn’t have the ability Magic has, but he had a flair, and he was very creative.”

Although the criterion for awarding an assist hasn’t changed since Robertson’s day, many, Robertson included, believe that scorers have become more liberal in awarding assists.

The NBA statisticians’ manual specifies that a player receiving a pass must “demonstrate an immediate reaction to the basket for an assist to be awarded.” If continuity is broken “by the receiver’s action to get position on an opponent,” no assist is permissible.

“Some players get 30 or 35 assists in a game,” Robertson said. “What is an assist today and what isn’t?”

Scott Skiles of the Orlando Magic recently set a record of 30 assists in a game. Porter had the record of 29 since 1977-78, when he was with the New Jersey Nets. Cousy and Rodgers had 28-assist games in 1958-59 and 1962-63, respectively.

Assist makers have been known to receive favoritism at home, but Bob Wanek, official scorer for the Milwaukee Bucks since they joined the league in 1968, pointed out that steps have been taken to guard against this.

“The league checks the ratio of assists to baskets at home and on the road,” Wanek said. “If it isn’t basically the same, they know something is wrong, and they see that it’s corrected.

“Once in a while we get a question about assists, but we always check our tapes, and we haven’t been proved wrong yet.”

Of his triple-double season, Robertson said, “I never even heard about triple-doubles ‘til the ‘80s. Everything about basketball now is a stat.”

Cousy, 62, now a television commentator for the Celtics, recalled that he performed his ballhandling trickery only when the situation warranted it.

“Court awareness is the key,” he said. “The defense dictates what you do. The idea of my behind-the-back stuff was not to abuse it, not to put on a show.

“If a guy overplayed me to the right side and I couldn’t get the ball out that way, I would pass it behind my back. It just happened to be the most convenient way of getting a pass off. Generally, my game was conservative.”

Cousy was asked if his fancy antics ever incurred the wrath of Coach Red Auerbach, now the Celtics’ president.

“Arnold tolerated it,” said Cousy, using Auerbach’s given name.

“I didn’t see anybody else doing this sort of thing until Ernie DiGregorio came along (in the early ‘70s). Now every 12-year-old kid in a schoolyard does it.”

Cousy believes that in addition to better shooting, the talent of today’s players makes assists easier to get.

“There’s a difference between creating assists and developing the opportunity for a teammate by passing to him at the opportune time,” Cousy said. “Point guards today don’t have to be as creative because their teammates are so good at getting position for shots.”

Assists became part of basketball statistics when the Basketball Assn. of America, as the NBA was originally called, was founded in 1946. Since the league was organized by hockey owners, it may be that the idea stemmed from the scoring system in hockey.

Said Leonard Koppett, who covered the BAA/NBA from its inception and is now a sports columnist for the Peninsula Times Tribune in Palo Alto: “It’s possible that the assist in hockey had something to do with it. However, the idea of assists was something that had been talked about.

“Pro basketball then was very rudimentary. For the first 15 years of the league, there wasn’t the slightest hint of uniformity. When Bob Cousy hit Boston, the Boston people went crazy.

“There were long arguments about what an assist was. There was a lot of complaining about ridiculous assist totals. Until the league established the rule in 1960, the stats were very unreliable.”

Koppett offered opinions on some of the game’s greatest playmakers:

“Cousy was popular not only for his spectacular play but for being perceived as a David against Goliath.

“I think Dick McGuire (older brother of coach-turned-sportscaster Al McGuire) and Andy Phillip were Cousy’s equal as playmakers, but Cousy was a much better scorer.

“Robertson was the first all-court, all-around basketball player. He was the first man that big who was that good.

“West wasn’t quite as big, and he didn’t quite have Oscar’s passing touch. If Oscar hadn’t been there, Jerry would have been regarded as the greatest all-around player.

“Magic and Stockton are tremendous in today’s kind of basketball, but player technique is so incredible now that a lot of their assists are less playmaking than just delivering the ball with an opportunity to score.”

Bob Rosenberg, who has been the official scorer for the Chicago Bulls since their inception in 1966, feels that some assist totals in the NBA are suspect.

“Certain scorers are too lenient,” Rosenberg said. “A guy isn’t supposed to get an assist if his teammate takes a dribble unless it’s on a breakaway, but a lot of them do.”

Scorers sometimes hear gripes, and Rosenberg cited two big complainers in Chamberlain and Johnny Kerr. The latter was an NBA player, coached the Bulls and the Phoenix Suns and is now the Bulls’ TV and radio color commentator.

“Wilt used to complain all the time,” Rosenberg said. “A Philadelphia writer, George Kiseda, told me once that Wilt thought he was always short-changed in assists. I said, ‘Nonsense. We don’t care who gets assists.’

“One time, Wilt saw the first-half stat sheet and came over and complained. But Kiseda had kept the assists on his own, and his total was the same as ours. After that, Wilt knew we weren’t cheating him.

“When Kerr was with the Suns, he said he was going to report me to the league because I was giving too many assists to Clem Haskins and not enough to his guy, Gail Goodrich. I said to him, ‘You never complained when you were here,’ and that ended that.”

Robertson never griped about such things, only about fouls that were called on him. It has often been said that he, like Rick Barry and a few others, never admitted that he had committed a foul.

Robertson might be expected to regret losing his assist record, but he insists that is not the case.

“I feel great about it,” he said. “Magic is a quality individual, and I’m real happy for him.”

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.