Victimized Brothers Help End Immigration Scam : Fraud: Illegal immigrants from Oaxaca were central to suit that unmasked firm selling worthless papers to foreigners.

For Martin and Pedro de Jesus Martinez, illegal immigrants from Mexico’s Oaxaca state, it seemed an ideal fix: Pay $300 each and obtain a document that they were told was akin to a mica, a U.S. residence card. And, supposedly, it was legitimate.

“That was one of the best days of my life,” Pedro de Jesus said, recalling the date in April, 1989, when he and his brother received the paperwork from a Del Mar-based firm known as the American Law Assn. “I wouldn’t have to be worried about being arrested anymore.”

A month later, while the pair were waiting for a bus in Carlsbad, a Border Patrol agent approached. Rather than flee--their first reaction honed by years of practice--the brothers proudly produced their documents. The lawman laughed.

“I’m sorry, but these are no good,” the officer said, signaling that he had seen similar forms from the Del Mar firm before, the De Jesuses recalled. Saying “Back to Mexico, muchachos!” he handcuffed them and put them in his vehicle.

The two didn’t realize it then, but that arrest began the unraveling of what California Rural Legal Assistance, a nonprofit immigrant advocate group, charges was one of the largest, most profitable immigration scams ever unmasked in California.

“It’s certainly the largest such case that we’re aware of,” said Stephen Rosenbaum, a San Francisco-based attorney for California Rural Legal Assistance, which provided legal assistance to the De Jesus brothers.

American Law Assn., owned by Susan M. Jeannette, a onetime paralegal and California notary public turned “legalization processor” in 1987, reached from the fields of northern San Diego County to the slums of Manila in the Philippines, generating hundreds of thousands of dollars in income for Jeannette and her associates, court papers show.

More than 1,000 foreign nationals are believed to have paid fees of up to $1,500 to have Jeannette and her colleagues process their postcard-sized applications for an obscure government initiative meant for agricultural workers. (The actual government application fee is $10.) Most were Mexican field hands living in San Diego County, like the De Jesus brothers, but the victims also included some Central Americans and scores of residents of the Philippines.

As it turned out, no one benefited. The program, known as the Replenishment Agricultural Worker initiative, or RAW, was designed to be activated solely in the event of a nationwide shortage of field help, but such a labor scarcity never materialized.

Last month, a Superior Court judge in San Diego, after a two-week trial on a civil action brought by the De Jesus brothers, ruled that Jeannette and an assistant, Leticia Ramirez, “committed unlawful, unfair and fraudulent business practices” in the operation of the American Law Assn. (which was also known as La Clinica de Ayuda--The Help Clinic.)

Judge Charles R. Hayes, who ordered the two to pay more than $400,000 in restitution to ex-clients, found that Jeannette’s firm engaged in false advertising, charged an “unconscionable fee” and deliberately defrauded clients, all in violation of consumer-protection statutes.

Both Jeannette and Ramirez have consistently denied the charges, saying they never made false promises and only charged reasonable fees.

But the judge found that the document that the firm commonly issued to clients--official-looking correspondence that was often stamped and notarized, embossed with the bearer’s photograph and/or fingerprints--was deliberately misleading, intended to impart an aura of government imprimatur.

“Hundreds of people were deceived by this document,” the judge stated. “For the hard-working people who testified in court, the prospect of immigrating to the United States, with the desire to better themselves and their families, was wholly illusory insofar as this document is concerned. The document has no value for the RAW program or for anything else except to deceive clients.”

Concern about immigration swindles has risen considerably in recent years, as revisions in U.S. laws have opened up complex new avenues for foreigners seeking legal status.

“One of the important things about this case is that it sends a message that undocumented people are not fair game,” said Claudia Smith, attorney in Oceanside for California Rural Legal Assistance.

The judge ordered Jeannette to pay $431,032 in restitution to more than 1,000 former clients. Ramirez was ordered to return $10,270 to 158 ex-customers. (The two were also ordered to deposit about $40,000 into a separate account whose fund is to be used in an advertising campaign designed to discover all of those bilked by Jeannette, who testified that she had destroyed most of her paperwork.) A jury awarded $28,000 to each of the De Jesus brothers, including damages and a refund of their original investment of $300 apiece.

Jeannette and her colleague must deposit the entire amount into a special account by Aug. 13. But the two have said through their attorney, Joe Auerbach of Solana Beach, that they are broke and unable to pay. Jeannette and her assistant plan an appeal of the Superior Court ruling, Auerbach said.

The pair have since abandoned their former practice and begun business anew as North County Legalization Services, operating out of the same Del Mar address. (Jeannette sold American Law Assn. in March to a friend, William Edward Drexler Sr., a disbarred attorney who was sentenced to a five-year federal prison term in 1982 for his part in an tax-evasion scheme in which ministries were fraudulently sold as tax dodges.)

Immigrant advocates say the scope of Judge Hayes’ order may be unprecedented in California. Among other things, Jeannette and Ramirez must now display signs, in Spanish and English, delineating precise fees and services; stating that they are not attorneys and informing potential clients that there is a court order governing the business--and that the order is available for public perusal.

2 Through their attorney, Auerbach, the two have contended that California Rural Legal Assistance and others were engaged in a “vendetta” against the business, a charge dismissed as ludicrous by the migrant-advocacy group and rejected by the judge.

Jeannette and her associate, Ramirez, declined to comment when contacted. There are no criminal charges against the business.

The fraud outlined in the judge’s ruling and court documents provides an unusually detailed portrait of what critics charge was a particularly prolific--and profitable--immigration scam.

To her clients and others, Jeannette has portrayed herself as a kind of Good Samaritan, offering much-needed hope to the thousands of homeless immigrant field hands who live in crude camps throughout northern San Diego County. She says she has assisted thousands in acquiring legal U.S. residence status. As part of her practice, Jeannette and her associates regularly visited the camps, hawking their purported expertise.

“I have a strong affection” for field hands, Jeannette said in an affidavit dated May, 1988, that is part of the voluminous court record. “If I find an individual that has been harmed, I get him free medical attention. If somebody can’t pay for the service, we do it for free. I take food and clothes to the workers. I pay out of my pocket, when I find an unfortunate individual who has no money for food.”

Even Jeannette’s critics acknowledge that she did help some immigrants adjust to legal status through various programs--although not via the agricultural worker initiative that was the focus of the lawsuit. “Jeannette got her share legalized, but she grossly overcharged,” said Stephen F. Yunker, a San Diego attorney who was the lead trial lawyer in the case.

In wordy missives to the migrant community, Jeannette often adopted a folksy yet ostensibly judicious tone.

“This column has always been used to inform the Hispanic community of the new forms of the legalization programs which have been available,” is how Jeannette began an article that ran in September, 1989, in El Latino, a Spanish-language newspaper that circulates in northern San Diego County. Her columns often appeared on the same page as her advertisements, for which she paid $150 apiece.

“I must warn you to be careful,” Jeannette cautioned in her 1989 column, largely an alert about unscrupulous consultants. “There are certain individuals who do not know the law or the program, and they are visiting the camps and are opening their offices. They go from camp to camp giving information, taking any amount of money from the workers to register them, and never return.”

The column appeared at the time that sign-up was starting for the Replenishment Agricultural Workers program, which eventually lured the De Jesus brothers and hundreds of other clients to Jeannette’s offices in Del Mar and Carlsbad.

According to court papers, Jeannette, 47, got into the immigration business in 1987, after the Immigration Reform and Control Act opened the possibility of legal status in the United States for millions of illegal residents. The law also spawned the RAW initiative for agricultural workers. Jeannette obtained a four-year notary public commission in January, 1987; the commission expired this year and has not been renewed.

Jeannette ran afoul of laws regulating notaries public, including a ban on advertising oneself as both a notary and an immigration specialist, Judge Hayes found. The judge also ruled that Jeannette violated a prohibition against the literal translation of the phrase “notary public” into the Spanish words notario publico. (Lawmakers have forbidden the literal interpretation, as notario usually connotes a lawyer-like position in Mexico and elsewhere in Latin America.)

In Del Mar, Jeannette worked in conjunction with an attorney, Edward H. Fitzgerald. Together, the two signed up clients in the Philippines via two representatives in Manila, according to court records. Filipino clients, solicited with letters addressed to “Dear Potential U.S. Citizen,” were charged $1,500 each. (Fitzgerald settled with the De Jesus brothers and cooperated in the case against Jeannette.)

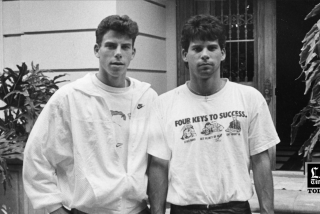

Attorneys say the De Jesus brothers were in many ways typical of those who signed up for Jeannette’s services. The two say they came to the United States illegally in early 1987. They have remained on and off since then, mostly doing field work and day labor in northern San Diego County, often staying in the migrant camps.

“There’s little for us at home,” explained Martin de Jesus, 24, a father of three who now lives with his 23-year-old brother in an Oceanside house.

Fed up with their constant lookout for immigration agents and the trouble they had finding work because of their illegal status, the two were intrigued in the spring of 1989 when a friend told them about La Clinica de Ayuda. The pair made the trip to the Del Mar office, paid the $300, and say they were “promised” that the document provided would shield them from arrest. They were each given a letter informing “To Whom It May Concern” that Jeannette was attempting to arrange legal status for them.

It came as a shock, they say, when, a month later, the Border Patrol agent laughed at the letter, apprehended them and sent both back to Tijuana.

“We thought we had our permiso, and everything was fine,” recalled Pedro de Jesus, 23.

Once back in the United States, the brothers visited the offices of Catholic Charities, where officials had already been contacted by others who say they were wrongly led to believe that Jeannette’s letter had afforded protection against deportation. A supervisor put the two and others in touch with California Rural Legal Assistance, where attorneys had long been suspicious of Jeannette’s operation.

The De Jesus brothers, saying they were anxious to right a wrong--and to get back their hard-earned money--agreed to be the plaintiffs in the bitterly contested lawsuit that led to the judgment against Jeannette and her operation.

The two were among 15 former clients of Jeannette’s who testified during the trial. Some had previously received anonymous threatening letters warning of potentially dire consequences if they took the witness stand. ‘If you are illegal,” the anonymous correspondent warned, “you could be apprehended and sent back to Mexico with or without your spouse and/or children!”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.