State Asks L.A. to Repay Sewage Plant Funds : Water: Auditors charge that the city is not treating as much effluent as it originally proposed, causing repeated spills.

SACRAMENTO — State auditors have recommended that the financially strapped city of Los Angeles repay millions of dollars in clean-water grants spent on local sewage treatment plants amid questions over how the city operates the facilities and whether the money was properly spent.

Concerns raised by the auditors range from repeated spills of sewage into a creek that flows into Santa Monica Bay to the expense of landscaping at a Japanese-style garden at one of the plants.

City officials strongly disagree with the audit findings, maintaining that the state auditors have failed to grasp the complexities of the city’s massive sewage treatment system. “We don’t think there’s a whole lot of credibility in the audit reports,” said Christopher Westhoff, general counsel for the city’s Board of Public Works.

The auditors contend, among other things, that since the mid-1980s the city has failed to treat as much waste water at facilities near Griffith Park and in the San Fernando Valley as envisioned by the state and federal grants. The result, they say, is that “a number of overflows of raw sewage” have been triggered closer to the coast, especially during wet weather.

Instead of treating the sewage upstream, the city pumps some of the waste water to the aging Hyperion Treatment Plant near Playa del Rey, where it occasionally backs up into Ballona Creek and flows into Santa Monica Bay, according to the auditors for the state controller’s office.

In interviews with The Times, the auditors cited 13 overflows between September, 1985, and last February that they said were probably attributable to the city’s failure to utilize the full capacity of its upstream plants.

Such spills have been a continuing problem that was underscored Nov. 21, when a sewer line leading into the Hyperion plant ruptured, releasing 5,000 gallons of raw sewage and forcing the brief closure of a stretch of beach.

In settlements with the EPA and the state, the city has agreed to correct the runoff problems at the Hyperion plant. But officials deny that their operation of the upstream plants can be blamed for the sewage spills.

The state auditors also contend that the city has not lived up to another purpose of the clean-water grants--to substitute recycled waste water for the fresh, drinkable water used to irrigate golf courses, parks and greenbelt areas.

City officials maintain that grants for one of the sewage treatment plants merely established a goal for reclaiming water, but did not require that it be met. They acknowledge, however, that the city failed to meet the requirements of grants for another plant that called for reusing 7 million gallons of water a day.

Altogether, the city has submitted final spending reports totaling about $120 million for a series of clean-water grants. In four reports recently made public, the state auditors recommended that the city repay about $80 million of the money to the EPA and the State Water Control Resources Board.

The next step is for the EPA to decide how much of the grant funds, if any, the city should repay.

John Ong, chief of construction grants for the EPA regional office in San Francisco, said his office is reviewing the state audits and views them as raising serious issues. But citing what he termed the generally high quality of Los Angeles sewer projects, Ong said he doubted that his agency’s final determination on repayment would be as punitive as recommended.

In a similar dispute involving San Diego, state auditors recommended that the city repay $36.6 million in clean-water grants used to build a treatment plant at Point Loma. In a recent ruling, the EPA scaled back that amount to $12.9 million.

For the city of Los Angeles, the squabbling over the funds comes at a time when it can ill afford to repay even a portion of the grants. City officials recently reported that they face a projected $57.1-million budget deficit.

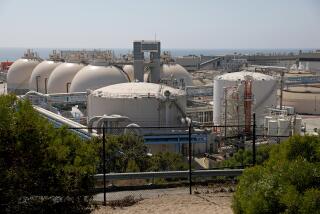

Much of the dispute between the state auditors and the city concerns about $66 million the city received to construct two sewage treatment facilities--the Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant in Van Nuys, which opened in 1984, and the Los Angeles-Glendale Water Reclamation Plant near Griffith Park, which opened in 1975. The facilities were built to sanitize waste water from at least 450,000 residents and relieve pressure on the Hyperion Treatment Plant.

One state official familiar with the state audit findings said that if it had been known “upfront” that the city was not going to operate the plants at full capacity, the grants from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the state Water Resources Control Board “wouldn’t have had to have been as large or as expensive.”

The official, who requested anonymity, said: “We paid for something that wasn’t necessary.”

The auditors, who reviewed the sewage contracts on behalf of the EPA, questioned dozens of smaller expenditures, including $1 million in landscaping that is part of the Japanese-style garden at the Tillman plant. The 6 1/2-acre garden--consisting of small lakes and carefully cultivated plant life--is a popular site for weddings.

The auditors say that some of the trees and shrubs came in containers larger than five gallons, violating state and federal expense regulations limiting the size of landscaping plants.

City officials said they are confident that “an objective review” will show that the landscaping costs were “necessary and reasonable.”

Edd Fong, a spokesman for state Controller Gray Davis, said the auditors are not saying that the problems they cite were intentional. “We’re not suggesting any fraud or corruption” by city officials, Fong said. “They may be honest mistakes.”

The Los Angeles officials see the city as a victim of a cumbersome bureaucratic review process. Bradley M. Smith, a division engineer in the city’s waste water program, complained that some of the issues raised by the auditors date to decisions made in 1969 or 1970. Smith said it is difficult to answer some questions raised by the state auditors because “in a lot of cases, there’s no one here who worked on the project.”

Underlying much of the dispute are conflicting views of the mission of the Tillman and Los Angeles-Glendale facilities.

Auditors say Tillman was designed to handle about 86 million gallons of waste water a day, especially during rainy weather. Based on inspections through early February, auditors said the Tillman plant “operated at about half of its designed peak flow capacity.”

They maintained that if the city used the full capacity at Tillman, it would probably reduce the overflows of raw sewage into Ballona Creek.

In a draft report on the Los Angeles-Glendale plant, the auditors contend that it, too, was built to eliminate sewage overflows and reclaim waste water. But they concluded that after 16 years of operation, “the city has not fully accomplished either goal.”

In their rebuttal to the Tillman audit, city officials say that the auditors are totally incorrect to suggest that the sewage overflows at the Hyperion plant are related to the way the Tillman plant is operated. They argue that the Tillman plant “was intended to relieve but certainly not ‘prevent’ such downstream wet weather overflows.”

The city officials also say that restrictions imposed by the Regional Water Quality Control Board and the AQMD limit the amount of waste water that can be treated at Tillman.

Another point of contention in the audits involves what the city does with the waste water once it is treated.

Geary H. Pena, audit manager for the EPA in Sacramento, said the grants were awarded to reclaim waste water for additional use after it is treated. “There’s a question whether (the city) did it or not. That’s the big issue.”

At the Los Angeles-Glendale plant, city officials agree with auditors that the grants spelled out that 7 million gallons a day would be recycled, but that only about 3 million gallons a day are being used to water Griffith Park. They say this reclamation program is being expanded.

At the Tillman plant, the city also has failed to meet its recycling goal, according to Peter G. Molteni, an auditor in the controller’s office. He said that when the city sought to build the facility, it said it would reuse 9 million gallons of treated water every day. When the state audits were conducted earlier this year, the city was not recycling any water, he said.

City officials contend that nothing in the grants for Tillman required them to recycle the water, but that they agreed to a goal of recycling 9 million gallons a day. “The intent is to reclaim the water,” said Angelo Incardona, assistant division engineer in the city’s waste water program.

Reflecting that goal, the city recently began to pipe 4.7 million gallons a day from the Tillman plant to an 11-acre lake in the Sepulveda Basin designed to sustain migratory birds.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.