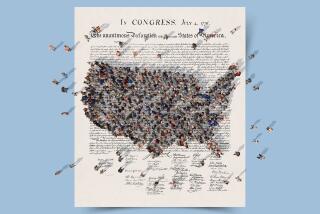

COMMENTARY ON BILL OF RIGHTS BICENTENNIAL : The ‘People’s Constitution’ Is at Risk If We Fail to Venerate It : As one jurist said, ‘Liberty lives in the hearts of men and women; when it dies . . . no law . . . can save it.’

In June of 1789, Representative James Madison fulfilled a campaign promise to his Virginia constituents by asking the First Congress to consider a group of constitutional amendments designed to secure basic individual liberties. On Dec. 15, 1791, 10 of these amendments were ratified by the states, becoming the federal Bill of Rights.

Lamentably, today, even as we celebrate the bicentennial of this venerable document, sometimes called the “people’s constitution,” ignorance, indifference, and intolerance threaten the viability of its renowned guarantees. In 1987 about 59% of the American public could not even identify the Bill of Rights. For over 40 years, surveys have shown that Americans are at best uninformed about the provisions contained within the Bill of Rights; and, at worst, are hostile to them.

In the 1990s, the “people’s constitution” is at risk from our failure to remember, declare, and venerate its promise of individual liberty. What is a nation to do? If we are not well educated about the Bill of Rights, its genesis and breadth, its promise will disappear from the hearts of all Americans.

Ironically, Madison and most other delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 opposed the addition of a bill of rights to the Constitution. Four arguments justified their opposition:

1) It was unnecessary in a constitutional republic founded upon popular sovereignty and inalienable natural rights. In addition, since many (but not all) states had bills of rights, federal guarantees were not needed.

2) A bill of rights would be dangerous, for, as Alexander Hamilton put it: “They would contain various exceptions to powers which are not granted; and, on this very account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. Why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do?”

3) It would be impracticable to enforce since its security would inevitably depend on public opinion, and on the general spirit of the people and of the government.

4) The Constitution is itself a bill of rights as is the constitution of each state, making further efforts to secure these rights redundant.

The absence of a bill of rights in the Constitution was a major obstacle to ratification and provoked some of the strongest protests by the Antifederalists in opposition to the proposed government.

George Mason of Virginia refused to sign the Constitution, saying that without a bill of rights, he would sooner chop off his right hand than put it to the Constitution as it now stands. In a representative government a bill of rights was absolutely necessary, argued the Antifederalists, “to secure the minority against the usurpation and tyranny of the majority.”

The Bill of Rights was the result of political pressure and political compromise. Since the Federalists were not so completely convinced of the undesirability of a bill of rights as to prefer the defeat of the Constitution to ratification with an accompanying bill of rights, they agreed to support a bill of rights once the First Congress was assembled. Consequently, Madison introduced 19 constitutional amendments to the First Congress in June of 1789.

Possibly influenced by Jefferson, Madison justified the submission of a bill of rights to Congress on “declaratory grounds.” Once these rights are declared and venerated by the people, as political philosopher Martin Diamond explains, they “serve as an ethical admonition to the people, teaching them to subdue dangerous impulses of passion and interest.”

The idea for a bill of rights stemmed from the English and American habit of making such declarations part of fundamental law. It was common practice for the American colonists to state their basic values and commitments as a society in one document such as a preamble and a bill of rights and to describe their form of government in a second document. Hence, the frequently found separation between a declaration or bill of rights and a constitution.

The great constitutional rights contained within the Bill of Rights are protections against majority pressures and majority power. Too often we forget that the Bill of Rights is part of the constitutional framework which protects us from the tyranny of the majority when we are weak, helpless, or just outnumbered. The Bill of Rights is an attempt to curb what Jefferson called “elective despotism”--the potential for tyrannical and perverse policies emerging from the elected branches of government.

Once the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791, Congress was forbidden to abridge free speech, press, religion, and so forth. However, state legislatures could abridge them (unless prohibited by their state constitutions)--and they did! Not until the Supreme Court utilized the “due process” clause of the 14th Amendment (passed in the aftermath of the Civil War in 1868), first in the 1890s and then more frequently in the 20th Century, were certain rights protected from invasion by local authorities.

This judicial doctrine is called “selective incorporation”--”incorporation” because certain rights are held to be incorporated within the due process clause of the 14th Amendment and therefore applicable to the states; and “selective” because the court retains the discretion of deciding which rights are in and which are out.

Citizens tend to assume they have a great many rights not contained in the Bill of Rights. For example, the right to housing, public welfare or employment are nowhere guaranteed in the Constitution. Citizens have no right to be free from hunger or impoverishment according to the “people’s constitution.”

Neither is the right to privacy mentioned explicitly in the Constitution, although the court has recognized that a right of personal privacy, or at least a guarantee of certain zones of privacy, is constitutionally protected. Most surprising of all, there is no constitutional right to education. These and other “positive rights” are absent from the “people’s constitution.”

While contemporary debate rages between libertarians and welfare rights theorists about the need for legally binding “positive rights,” philosophical, experiential and purposive constraints limited their consideration by the First Congress in 1789. While the Bill of Rights permits individual freedom from government, as written, it does not necessarily enable the exercise of individual freedom.

The Bill of Rights is not self-enforcing, nor, as history has shown, can we always depend on the national government for its enforcement. Rather, enforcement depends on the vigilance and education of all Americans. As the renowned jurist Learned Hand noted: “Liberty lives in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it; no constitution, no law, no court can even do much to help it.”

The “spirit of liberty” which emanates from the Bill of Rights needs to be kept alive by each new generation of Americans. The promise of the past is only a possibility for the future if this spirit is nurtured by education, self-reflection, appreciation, and toleration.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.