Finally, a Home : After Living on Streets of Westchester in High School, Sam Crawford Has Stability at New Mexico State

LAS CRUCES, N.M. — The dusty roads of the Mesilla Valley are a world away from the streets that New Mexico State point guard Sam Crawford knew when he played at Westchester High in Los Angeles.

Crawford, who leads the nation in assists, knew the sidewalks that wind through Westchester and Inglewood like the back of his hand. He spent many nights walking them. At 16, cast out on his own, home was the back seat of his car, a teammate’s couch or an empty garage.

How the 5-foot-8 Crawford wound up a star in this Southwestern town 45 minutes north of El Paso is the tale of a youngster cheated out of his adolescence.

“Everything passed me by before I could grasp it,” he said. “It wasn’t normal. I grew up too quickly, both as a player and as an adult.”

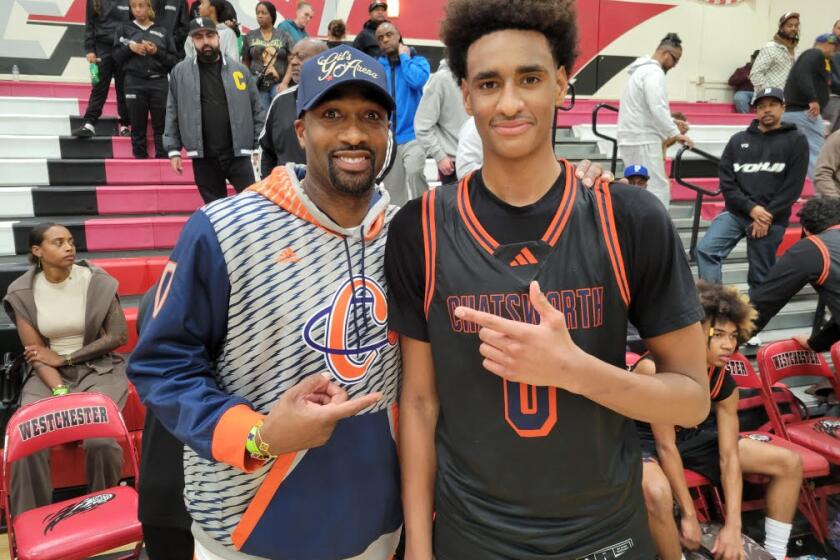

Crawford is 21 now, but he was 10 when his mother sent him to Southern California to escape Chicago’s crime-riddled housing projects. For six years he stayed with an aunt, Mita, and her husband, former Laker reserve guard Ron Carter. But the couple’s marriage crumbled, and in 1987 Crawford’s aunt went to a detoxification center for treatment of alcohol abuse. Crawford, a junior in high school, was left to fend for himself.

“He just kind of hung out on the streets,” Westchester Coach Ed Azzam said. “He never really had anywhere to go. He bounced around.”

Crawford took odd jobs washing cars, painting fences, cleaning buildings. He moved from place to place, sometimes sleeping at the homes of teammates. He showed up for classes just enough to remain eligible for basketball, one of the few things he enjoyed.

“There’s no question that if I didn’t have basketball, I would have killed myself or had myself committed,” Crawford said. “That’s how bad it was.”

The Westchester gymnasium was Crawford’s living room. He was a flashy crowd-pleaser who loved to pass. He passed up good shots for no-look opportunities and alley-oop passes that led to thunderous dunks by teammates such as Zan Mason, now sitting out a year at Loyola Marymount after transferring from UCLA.

Some of Crawford’s passes, though, were as wild as his attitude, which grew more callous by the week. One afternoon, when Carter showed up at a Comet practice, Crawford engaged him in a fistfight.

“The anger and frustration of my life showed,” Crawford said. “I was vulgar, outspoken, frustrated.”

Still, as a junior at Westchester, he averaged 17.4 points and 8.6 assists.

Said Azzam: “He gets off on giving people the ball. But at times he tries to make the pass that leads to the basket instead of making one more pass to the basket.”

As a senior in the 1988-89 season, both he and Mason, the recipient of many of Crawford’s passes, were named to the City Section 4-A all-star team, despite Westchester’s disappointing 16-6 season.

Several Division I schools wanted him. But he did not graduate on time because he had stopped going to classes after the season ended. He later made up his classes, but by then the colleges that had courted him, among them New Mexico State, had made other plans.

Crawford, looking for a place to start over, moved to Big Spring, Tex., east of Odessa. He intended to play at Howard College, a two-year school, but quit after the first day of practice.

“It was horrible,” he said. “There were 30 guys trying out for the team. I couldn’t take it.”

In late September, Crawford placed a call to New Mexico State assistant coach Gar Forman, a former coach at College of the Desert in Palm Desert. Forman referred Crawford to Moorpark College in eastern Ventura County.

“I didn’t know a lot about Sam at the time,” Moorpark Coach Al Nordquist said. “I knew he was a good player, but I didn’t know all the details about his life.”

Nordquist and Crawford clashed almost immediately.

“I wasn’t sure he would play, because I didn’t think he’d get through our conditioning program because he didn’t work hard enough,” Nordquist said.

Crawford had also returned to old tricks. He got a job selling cellular telephones in his old neighborhood and that proved more lucrative than going to school.

When Nordquist benched him for the first time, Crawford thought about quitting basketball.

“I was exhausted with (trying to survive and play at the same time),” Crawford said.

But he didn’t quit. Through business contacts, Crawford met DeeDee Purvis, a cheerleader at El Camino College in Torrance. It was a turning point in his life. For the first time, he felt as if someone really cared about him. Crawford admired DeeDee’s mother, Mildred, who took an interest in his well-being. When DeeDee asked Crawford not to embarrass himself on the court, Crawford obliged.

“He was always screaming and yelling at the referees,” DeeDee said. “He acted like an animal.”

Moorpark advanced to the state playoffs both seasons Crawford was there. In his sophomore season, 1990-91, Crawford was named a community college All-American. He averaged 13 assists and set school records for assists, 20, and steals, 10, in a game. He also was shooting more often, averaging 20.5 points a game.

Said Nordquist: “One thing he can do is accept discipline very well. He’s not afraid to admit when he is wrong. You hear the horror stories and see the things he pulls sometimes and you believe the guy is not all there. But he’s really a fine young man with a lot of talent.”

Crawford and DeeDee were married last summer. When they arrived in Las Cruces in September, Crawford was like a new man. McCarthy, who welcomed nine junior college transfers and only one returning starter, was impressed.

“At the beginning of the year (Sam) was a full step ahead of (the other players),” McCarthy said.

Crawford had 22 points in a 90-77 double-overtime victory at University of the Pacific Jan. 18, the highest total by an Aggie this season, and his average of 12.7 points leads the team. Because he has been asked to shoot more, his nation-leading assist average has dwindled from a high of 10.1 a month ago to 8.9.

Crawford sees that as a concern, but, said McCarthy, whose team is 13-2: “I have to tell Sam not to be too hard on himself. He’s always looking to make the pass when sometimes he should be taking the shot.”

Crawford has twice tied a New Mexico State record with 13 assists in a game and is on a pace to break the school record of 187. He had 11 last Saturday in a 74-67 Big West Conference loss to Nevada Las Vegas, which ended the Aggies’ 10-game winning streak.

Said Crawford: “You have to be willing to make mistakes and take chances, throw the ball to open spaces, read people’s minds. Either you are going to be good or you are going to be terrible. Guess you can say it’s living on the edge.”

DeeDee, originally from Las Vegas, has seen changes in Crawford since they moved to New Mexico.

“He has changed dramatically,” she said. “I wouldn’t say he was immature back then. He has always been very mature for his age. But by leaving California and coming to a different state, it created a whole different set of possibilities for him.”

Crawford has felt the changes in himself, as well.

“One thing I haven’t been credited with is being able to make the adjustments I’ve made in my life,” he said.

A surprise storm blanketed the Mesilla Valley with six inches of snow earlier this month, the night before New Mexico State played host to Cal State Long Beach. Crawford was on the streets of Las Cruces until the early hours of the morning playing in the fluffy, desert-dry powder with DeeDee. It was reassuring, he said, to finally know that he had a place to call home when the night was done.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.