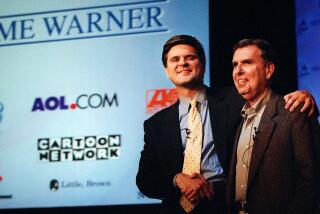

Time for Vision : New Time Warner President Gerald Levin Is a Strategist

For years they were fierce rivals within the high-stakes corporate worlds of Time Inc. and Time Warner in New York N.J. Nicholas Jr., the tightly wound financial expert, and Gerald M. Levin, the scholarly strategist.

Nicholas gained the upper hand in early going, and he went on to become president of Time Warner. But in the end, the company’s strategic interests won out.

On Thursday, Levin was named president and co-chairman of Time Warner in place of Nicholas, who was forced to resign while vacationing in Aspen after feuding with Chairman Steven J. Ross and other senior executives. Industry sources said Nicholas would get up to a $15-million severance payment.

Levin’s reputation for innovative thinking, especially in the area of cable television, made him the more logical heir to the ailing Ross in a company that clearly sees its future in the visual media, sources said. He is also seen as being most in sync with Ross’ global entertainment vision.

“Ross and the board clearly have faith that (Levin’s) the one who can take the company forward,” said financial analyst John Reidy of Smith Barney in New York. “This is it. Done. It’s over with. Finished. Levin is the successor.”

Wall Street responded favorably to the move, pushing Time Warner stock up nearly $2 a share, to $99.75, on Friday. So did company executives, who said Levin is one of the few managers popular with both Time and Warner loyalists.

“I’ve known him for a long time, and he’s a tremendous executive,” said producer Lee Rich, who works on the Warner Bros. lot. A Time magazine employee who asked not to be named said Levin “actually seems to like journalism.”

At 52, Levin is described as a quiet man who spends much of his free time watching movies and TV shows. He’s a devoted runner who puts in three miles a day “injured or not,” in the words of one friend. He’s also considered a workaholic. Associates say he often can be found in his office past 9 p.m.

Another friend credits Levin with having a photographic memory. He recalled that the executive once recited a speech verbatim after reading it just once.

In a 1988 interview, Levin described himself as a child of the visual age. “I went to the movie theater every Saturday morning without fail, and when television started in the 1940s, I watched all the time,” he said.

Levin joined Time in 1972, after working as a lawyer and international consultant. He even spent a year working in Tehran before the fall of the Shah of Iran. In the mid-1970s, he was widely credited with helping to create the cable television business. It was Levin, as head of the Home Box Office division, who persuaded Time executives to invest $6.5 million in a satellite service that made HBO available to cable television systems nationwide.

But by the mid-1980s, Levin’s star had faded at the conservative publishing conglomerate when he was unable to repeat the same success with the video division. And in 1986, he lost out to Nicholas for the Time presidency.

Given the title of Time’s “chief strategist,” Levin became an early advocate of diversification. In the recently published book, “To The End of Time,” author Richard Clurman writes that it was Levin who sounded the call for a “transforming transaction” that would ensure Time’s future.

That transaction occurred in 1989, when Time and Warner consummated the biggest corporate merger in history. Levin was named chief operating officer of the combined companies. Time Warner’s cable televisions operations remained an abiding concern--Levin once told associates: “Everything I am I owe to HBO”--but Levin also played a big role in searching out strategic partners.

Sources say he supported Ross’ plan for selling a 12.5% interest in Time Warner’s filmed entertainment and cable business to Japan’s Toshiba Corp. and C. Itoh & Co. for $1 billion last year. It was a move to reduce the company’s staggering debt, and Nicholas opposed it. Levin was also a strong proponent of the company’s cable station expansion experiments, a pet project of Ross’.

Still, few anticipated such a swift and surgical removal of Nicholas, widely regarded as a bright but brittle man who often alienated associates. One executive with close ties to the company said he was “shocked.” Another, who prides himself on his insider knowledge, said there was not even a hint.

Many believe that Levin’s promotion was accelerated by Ross’ battle with prostate cancer. “Nicholas and Ross were increasingly incompatible personally,” said Clurman, a former Time executive. “The fact that Steve hasn’t been well heightened the concern about whether (Nicholas) could succeed him . . . and that question was answered far and wide negatively.”

Clurman and others stressed that Ross, considered one of the corporate world’s most brilliant strategists, cannot be easily replaced. But in Levin, they say, Time Warner has found someone who at least possesses the best qualities from both Time and Warner.

“Obviously, he’s not Steve Ross,” said one company source. “But neither is anyone else.”

Bio: Gerald Manuel Levin

Named co-chief executive, Time Warner Inc.

Age: 52

Born: Philadelphia, Pa.

Education: BA, Haverford College, 1960 (Phi Beta Kappa); LL.B., University of Pennsylvania Law School, 1963.

Family: Married Barbara Riley, 1970. Five children.

Resume: Has been chief operating officer of Time Warner Inc. since May, 1991, and vice chairman since July, 1989. Previously, Levin had been vice chairman of Time Inc. since July, 1988. He joined Time Inc. in 1972 as one of the first staff executives of Home Box Office, serving subsequently as vice president of programming before being named president in 1973 and chairman in 1976. In 1979, Levin was appointed group vice president for video for Time Inc., overseeing all of Time Inc.’s cable TV interests. He was named executive vice president and “chief strategist” for Time Inc. in 1984 and vice chairman in 1989. Before joining Time Inc., Levin was a consultant with Development & Resources Corp. and from 1963 to 1967 was an associate with Simpson, Thacher & Bartlett in New York.

Business philosophy: A futurist who believes in long-term growth for the company.

Quote: About what he learned from David Lilienthal, famed head of the Tennessee Valley Authority, for whom he went to work in 1967: “From him I learned the concept of management as a humanist art . . . and technical skills--and not to be afraid of technically oriented subjects.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.