GM Posts Loss of $4.5 Billion, Lists Closings

DETROIT — General Motors reported a record annual corporate loss of $4.5 billion on Monday, targeted 11 factories with 16,300 workers for shutdown and announced a bureaucratic overhaul that comes sooner and reaches deeper than expected.

GM’s loss--capped by a $2.5-billion fourth-quarter deficit--made 1991 the worst year ever for the U.S. auto industry and brings the total red ink generated last year by Detroit’s Big Three auto makers to $7.6 billion. Earlier this month, Ford Motor Co. reported a $2.3-billion loss, and Chrysler lost $795 million.

In 1991 the U.S. auto firms were battered by recession, an unprecedented drop in consumer confidence and relentless competition from the Japanese on quality, engineering, design and image that cut steadily into their market share and slashed profit margins beyond the vanishing point.

“It’s clear the government isn’t going to help, it’s clear there aren’t going to be (trade) restrictions on this market. By God, we have to compete,” said Chairman Robert C. Stempel.

But some analysts now believe the worst is over for the time being, both in terms of the recession and the vulnerability of the Big Three. Ford and Chrysler in particular have drastically slashed costs and stand to return quickly to profitability as a recovery takes hold.

Stempel has been criticized for acting too slowly, and it remains to be seen whether these latest actions will be enough to restore competitiveness to GM--a company that lost $1,600 on every vehicle it built last year. But David Cole, head of the University of Michigan’s Office for the Study of Automotive Transportation, said, “I did not think Stempel would go as far as he did today.”

On Monday ailing auto giant GM unveiled a reorganization that will undo much of the sweeping change imposed in 1984 under then-Chairman Roger B. Smith. His successor, Stempel, called the latest action an assault on GM’s bloated middle-management ranks.

GM also identified 11 of the 21 assembly, engine and parts plants it has pledged to padlock by 1995 and an additional plant whose engine production will be slashed. The company sent a strong signal to workers by saving a Texas plant willing to make labor concessions instead of a Michigan plant that was considered inflexible.

The plants in Arlington, Tex., and Ypsilanti, Mich., make the same kind of cars but both are operating at half-capacity. GM announced in December that one or the other would close.

The naming of the 11 plants--two others were previously identified--hastens the factory retrenchment announced in December aimed at eliminating 74,000 jobs by 1995. The remaining eight plants will not be chosen for “several months,” GM said.

Among those spared for now was an Orion Township, Mich., assembly plant. But like many others, the Orion factory still faces many more months of uncertainty.

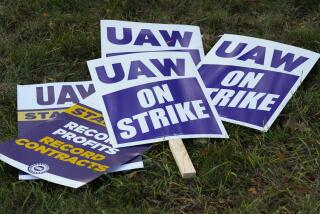

“This was not a joyous occasion at the Orion plant,” said Ernie Emery, president of the United Auto Workers local. “There’s going to be a lot of uncertainty up through the coming year.”

When completed, the cutbacks will leave GM’s U.S. car and truck business with about 320,000 employees, just half as many as in 1985.

Since the December announcement, there have been signs of a recovery in auto sales and the price of GM’s stock has surged about 40% to $38 a share. But Detroit came under harsh criticism in the meantime after its top executives traveled to Japan with President Bush to call for easier access to the Japanese market.

Attacked for their high executive salaries as they ordered wholesale layoffs of workers, Big Three leaders are rumored to be laying plans to slash managerial pay. But Stempel indicated Monday that little was forthcoming on that front beyond the 50% cut in total executive compensation each of the past two years by the elimination of stock and cash bonuses, the result of GM’s losses.

GM did confirm that its board has ordered a watering down of executive pensions that could significantly reduce the pensions received by about 100 top retirees, including ex-chairman Smith. The pension plan was sweetened just before his 1990 retirement, giving him a $1.1-million annual payment.

GM officials declined to say how big a hit Smith will take.

The GM annual loss reported Monday was apparently the worst ever by a U.S. corporation, narrowly surpassing a $4.4-billion drubbing endured by oil giant Texaco in 1987 after losing a landmark court case to Pennzoil. Although other companies have reported larger quarterly deficits, they managed to offset those losses somewhat through the rest of the year.

But the terrible showing was no surprise, and in fact the company did better than some analysts expected in its fourth quarter. GM’s woes are such that it described the October-December operating loss of $520 million as a “significant improvement.”

“We’re getting our hands around this Kamikaze that has been going down like a rock,” Stempel told a news conference at GM headquarters, referring to the company’s cost-cutting efforts to slow the financial hemorrhaging.

However, the fourth quarter net loss hit $2.5 billion because GM took a one-time charge of $1.8 billion, after taxes, to cover the anticipated cost of closing all 21 plants over the next three years. The special charge also inflated the full-year loss, which otherwise would have been $3.4 billion.

The net loss occurred despite record or near-record earnings at GM’s big finance, computer and aerospace subsidiaries as well as its European car and truck business.

One analyst, John Casesa of Wertheim Schroeder Inc. in New York, estimates that GM actually lost a staggering $7.4 billion on its North American car and truck business alone last year, an average of $1,600 per vehicle.

GM’s latest reorganization, rumored in recent weeks, appears to take aim at the heart of GM’s efficiency problems, said Casesa and David Cole, head of the University of Michigan’s Office for the Study of Automotive Transportation.

Among other things, it will gradually eliminate the three entities known as the Buick-Oldsmobile-Cadillac, Truck and Bus, and Chevrolet-Pontiac-Canada vehicle-building groups, created by Smith but now viewed as bureaucratic roadblocks and nesting sites for unneeded middle managers.

“This says that the reorganization in ’84 was either not right or wasn’t enough, and the financial pressure is forcing GM to change at a much faster pace,” said Casesa.

The company has lagged behind Chrysler and Ford in streamlining the bureaucracy to bring new vehicles to market faster. All have established, in varying degrees, “platform teams” that vault over the walls erected by such traditional fiefdoms as design, engineering, manufacturing, finance and marketing.

Stempel said the new arrangement will more nearly resemble that of GM’s profitable and growing European auto operations. But the model for so-called platform teams is the Japanese, who have been able to bring new vehicles to market in three years versus four or five years in Detroit.

GM shares fell 62.5 cents to $37.75 on the New York Stock Exchange on Monday.

* RELATED STORIES: D1, D2