View of Model Multiethnic City Vanishes in Smoke : Relations: Disturbances bare a simmering racial anger that community efforts never fully quelled.

Like a bandage stripped off an open wound, the civil unrest sweeping through South Los Angeles in the last two days has exposed and intensified the painful strains of racial anger and ethnocentrism that have long simmered among the city’s myriad ethnic communities.

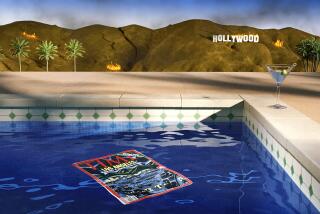

The popular notion advanced by Mayor Tom Bradley and other civic leaders in recent years that Los Angeles was transforming itself into a harmonious, multiethnic model city appeared to waft away amid the acrid smoke billowing over the city.

Each new graphic televised image--black, Latino and white looters rampaging through ruined stores, white police officers and National Guard soldiers advancing to retake city streets by force, dazed white and Latino passersby beaten by angry black assailants, frightened Korean merchants guarding their shuttered markets with guns--threatened to reinforce the long-held fears and prejudices gnawing at the city’s populace, worried community leaders and race relations experts said Thursday.

The countless scenes of South Los Angeles residents rushing to help strangers caught in the cross-fire were obscured by an onslaught of chaos and anger.

“My fear is that all that we’ve worked toward could be lost if people let their basest instincts take over,” said John Mack, president of the Los Angeles Urban League. “I worry about the reactions we will get from the white community. Just because there are irresponsible black people out there exploiting this situation is no reason to assume that all black people are looting and burning.

“In the same way,” he added, “it would be dangerous for the black community to assume that the actions of a few white officers stand for the beliefs of the entire white community. Now is not the time for generalizing.”

But even as Mack spoke, after a round of meetings Thursday with anxious civic leaders, his fears seemed to be coming true. Across South Los Angeles, blacks, whites, Latinos and Asians met in scores of violent confrontations city residents will not soon forget. And inside untold numbers of homes and offices, Angelenos soaked in the numbing scenes of violence and reacted instinctively with words of anger and fear.

A white Simi Valley doctor said the riots gave credence to the officers’ defense that their lives are threatened every day and they saw King as another deadly threat.

“I had felt they were guilty of excessive force from watching the video,” he said. “But I feel more empathetic to the officers after this. . . . I hope the jury did the right thing. Yesterday, I would have found them guilty. Today I probably wouldn’t.”

Sitting forlornly in his ransacked car audio store in the 1700 block of Vermont Avenue in South Los Angeles, Eddie Rho, 36, the Korean co-owner, surmised that the anonymous looters who plundered his business were black. The store was targeted, he said, because of the expensive stereo equipment he sold, but he also wondered if it was because he is Korean.

“They knew we were Koreans here,” said Rho, who expects that relations between blacks and Koreans will now “be tougher.”

“From now on I can try to be close to them, but they won’t be close to us,” Rho said.

His assumption that the looters were African-American belied the multiracial composition of rioters that swept through many parts of the city. Black activist Michael Zinzun, who led Wednesday’s protest at Los Angeles police headquarters, blamed much of the violence that followed the rally on white punk-rockers, radicals and college students.

At the corner of a devastated stretch of Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and Western Avenue, where a mini-mall was raked by flame, a car stopped in the middle of the street and disgorged a group of young black women, who performed a taunting dance a few feet away from six shotgun-wielding police officers facing off a crowd of angry residents.

After stalling traffic for 10 minutes, the dancers piled back into their car. As they drove off, they shrieked at the officers, “White devils! White devils!”

Much of the anger underlying the tensions between the city’s ethnic groups could be found any place that different racial groups are thrown together, said Michael Preston, an associate professor of political science at USC who has studied race and politics in Southern California.

But those currents are stirred even more by the fact that several of the city’s most visible groups--blacks, Latinos, Asians, working-class and poor whites--are all jockeying for position in the scramble to win a limited supply of jobs, dwellings and economic opportunities.

“At the elite level in Los Angeles, you’ll see a surprising degree of cooperation between Asians, blacks, Jews, Hispanics,” Preston said. “But below those levels, you have clear tensions because the pie is shrunken. Everyone wants a piece and resents it when another group of people have something they don’t. And unfortunately, blacks always seem to be the last ones who get to the plate.”

Preston and other race relations experts say that tensions in the aftermath of the King beating were inflamed by gaps in perception between racial groups.

“In general, blacks perceive much more discrimination than whites perceive,” Preston said. “Many blacks see changes in the Police Department as only the tip of the iceberg, that it’s only a part of a broader issue.”

And in the wake of the first full day of riots, said another race relations expert who declined to be named, there appears to be a schism in how blacks, whites, Asians and Latinos perceive the city’s current crisis.

“Whites, for the most part, will look at these scary scenes on television and conclude that the greatest concern right now is quelling the unrest, staving off black people that they see as threats to their welfare,” the observer said.

“But even though a lot of blacks are equally frightened,” he added, “that concern is matched by their anger and their dismay over the failure of the judicial system. I worry that we’ll come away from these last few days permanently divided.”

The boiling rhetoric of racial conflict, evoking riots that swept Watts, Detroit and other American cities in the 1960s, resurfaced Thursday as if it had never left.

“Justice is supposed to be blind, but in this case, justice is black and white,” said Frank Holoman, owner of the Blvd.Cafe on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. “This is a message that will go all around the world. If you’re a black man or black woman in L.A., don’t expect justice.”

And at a coffeehouse in South Pasadena, a black man pitched a table through a plate glass window, screaming, “The party’s over!” Terrified white patrons cowered behind ice cream freezers and under tables while the man smashed mirrors, neon signs, the espresso maker and the counter, said Colette Richards, the shop’s 28-year-old owner.

Afterward, the shaken owner could only conclude that the shop was attacked because it is a nightspot popular among affluent white customers.

“We were the perfect target,” Richard said. “They hit us because there are all these people outside, and a majority of them white people.”

At the corner of Vermont Avenue and 24th Street, David Gitis, a Russian immigrant, surveyed the bare ashes of his hardware store. He thought his business was safe because he had been in the neighborhood for three years and thought he was seen as a welcomed resident of the community. But now he blamed the destruction of his business on Latino gang youths.

“It’s hurt me,” he said. “I can’t sleep, I can’t eat. It’s like they killed me, and for what? What did I do wrong?”

Gitis said he will never run another business in a black or Latino neighborhood. “I’m afraid of them,” he said.

Some Los Angeles civic leaders and community activists suggested bluntly Wednesday that the city’s frayed political coalitions can only survive after the riots if leaders are able to broaden their membership and toughen their dialogue.

Local leaders said that will require powerbrokers to attract and empower new leaders from the city’s most disadvantaged communities who have not had a voice in the city’s political process. And it will require leaders to listen more closely to their hard-edged plaints and back up their promises with action.

“There’s a lot of anger, particularly in the underclass,” said Dr. Bill Hayling, founder of 100 Black Men, one of the city’s most influential minority leadership factions. “A lot of people have been left out of the system. Because they were left out, this boiled over. As leaders, we have to heal. It’s doable. But it will take an awful lot of effort.”

Richard Riordan, an attorney and businessman who plays a central role in city affairs--and who pledged Thursday to help riot-torn businesses rebuild--defends the city’s leadership. In Riordan’s view, the “process worked.”

“In the Christopher Commission, we had the best minds in the city--Republican, Democrat, blacks, whites, all different colors--work together on solutions to the major problems facing us,” Riordan said.

But at the same time, even Riordan has acknowledged his frustration recently in trying to persuade the city’s corporate powers to donate funds to the effort to pass a charter amendment to enact reforms within the LAPD.

Yet even as the drab commercial strips burned to cinders Wednesday night, some angry black residents were clearly giving up--not only on Los Angeles’ Establishment, but on their own as well.

Midway through the rally for civil order at the First AME Church in South Los Angeles, Mayor Tom Bradley’s call for peace was interrupted by catcalls.

“What are you going to do? What are you going to do?” one woman yelled again and again.

“Sit down!” another woman shouted.

A few minutes later, a young black woman pushed her way to the podium, stepping ahead of the clergy and elected officials who had been invited to speak. When the crowd began chanting, “Let her speak!” rally organizers briefly gave her the floor.

“We can’t rely on these people up here to act,” she cried out, pointing behind her at the assembled community leaders and politicians, among them City Councilman Michael Woo and State Sen. Diane Watson.

“I believe they have our best interests at heart, but we cannot rely upon them,” she said sternly. “You know what you need to do.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.