Over the Edge? : Riveting or Repulsive, Jim Rose’s Sideshow Draws Young Trendies to See Mr. Lifto and the Human Pincushion

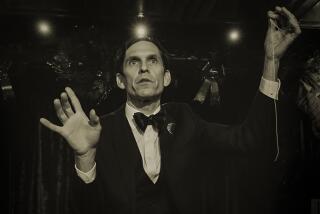

SEATTLE — On a stage cluttered with chains, broken glass and a bed of nails, Jim Rose paces like a caged man.

His jeans sag from his wiry, punished torso. His red-rimmed eyes squint out at the hip crowd jammed into the Crocodile Cafe. Rose stops, plants his feet wide, tucks a railroad spike into one nostril and begins to hammer the iron stake into his nose: the Human Blockhead.

The audience is on their tiptoes. Moans and shrieks. Some people cover their eyes; others cast furtive looks at their companions.

“People come to see who’s going to pass out,” says Jeff Gilbert, music director for KZOK-AM, a local rock station. “At every show, someone loses their lunch.”

Rose, a 38-year-old former Venice Beach performer, has staged a triumphant comeback of the freak show, a bit of Americana that has been essentially moribund for half a century. From 1840 to 1940, hundreds of shows roamed the country, bringing amazement and disgust to dusty small towns.

Today, there is only the Jim Rose Circus Sideshow.

In marked contrast to the yokel audiences of yore, Rose and his scruffy band are attracting sophisticated art students in Doc Marten clodhoppers and trendies from the alternative-music scene, atwinkle with nose and eyebrow rings.

They come to see the Amazing Mr. Lifto dangle two steam irons and a cinder block from the rings in his pierced nipples, and to see Dolly the Doll Lady, an aging circus dwarf, feed live slugs to the sword swallower--all to the thump of a soundtrack by Talking Heads and Slayer.

Another crowd-pleaser: Matt (The Tube) Crowley, formerly a Montana pharmacist, ingests several quarts of beer, chocolate sauce and ketchup through a tube in his nose. For an encore, he pumps the bile beer up again.

Such stunts--each an updated version of a traditional sideshow act--have made Rose a cult sensation in the Northwest. At local clubs, the ritualistic scene surrounding a Rose show is reminiscent of the “Rocky Horror Picture Show” phenomenon. Obsessed fans return to view the acts again and again; followers even memorize and parrot lines from Rose’s onstage patter.

And now Rose’s fame has spread. The sideshow is the non-musical hit of the 30-city Lollapalooza tour, the so-called post-punk Woodstock that winds up Sept. 11-13 at the Irvine Meadows Amphitheater.

On the strength of their Lollapalooza showing, Rose’s troupe was recently signed by Triad Artists, a Los Angeles talent agency. “Word’s getting out,” says Triad agent John Branigan. “We’re getting calls from all over the country.”

Even the fact that some people find the show offensive is working to Rose’s advantage, Branigan says: “If people find it offensive, they walk out and tell their friends--and their friends come to see the show.”

Today, the concept of exhibiting physical anomalies for profit is shocking. But until the turn of the century, Siamese twins, amputees, microcephalics and people with other abnormalities were routinely put on display, according to Robert Bogdan, author of a study of freak shows and a professor of special education and sociology at Syracuse University in New York.

It was only when medicine put a name to some of the conditions that cause deformity that it became uncouth to gawk, Bogdan says.

Also contributing to the gradual demise of freak shows was the rise of the disability rights movement. “The freak show is to disabled people as the striptease show is to women, as Amos ‘n’ Andy is to blacks,” Bogdan says in his book, “Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit.”

For his part, Rose says he is simply filling a cultural niche left vacant since the early shows vanished. “The times just caught up with me,” he says.

“People are tired of things that are slick, contrived, manipulated, clean and choreographed,” he adds, explaining the show’s appeal. “So many people are jaded. They want something live, real, raw and dangerous.”

His newfound fame has come as a surprise to Rose, a shrewd contortionist with the agility of a figure skater and the promotional genius of P. T. Barnum.

“At this time last summer, I was putting my face in broken glass for spare change on Venice Beach,” he says.

Rose says he grew up in Phoenix but is otherwise vague about his past, only hinting that he once came close to living on the streets. His fascination with circus sideshow performers dates from childhood, he says. As a young man, he taught himself such tricks as sword-swallowing and fire-eating--stunts requiring years of practice in voluntary and involuntary muscle control. Rose polished his training in Europe, where sideshows are more accepted than in the United States.

He began plying his trade during the summers at Venice Beach--he was known as Jimmy the Geek and the Venice Beach Rubber Man--and in Paris, where he met his wife and assistant, Bebe Aschard.

In the winters, when the Venice boardwalk rolled up, Rose worked the Ali Baba, a Middle Eastern restaurant in Seattle, as relief for the belly dancer. “I couldn’t pay people to come see the show,” he says.

His big break was meeting Graham (he goes by first name only), proprietor of Seattle’s ultra-trendy Crocodile Cafe, the former haunt of the now-famous grunge bands Nirvana and Mudhoney. A longtime collector of circus sideshow memorabilia, Graham was the first to recognize that Rose was more than a sidewalk hustler.

“What he does is performance art,” Graham says.

When Rose dragged his swords and chains onstage at the Crocodile, he became the instant darling of the grunge rockers.

Also contributing to Rose’s popularity was the rise of an underground movement known as the Modern Primitives. Followers of the movement find spiritual and transcendent possibilities in tattooing, piercing and other forms of body alteration.

Once word of Rose’s show got around, people began to come out of the shadows to audition unbidden. The sideshow ringleader discovered a number who had also become fascinated with circus acts and “body play” at an early age, and who had taught themselves bizarre tricks.

For example, the Amazing Mr. Lifto (he declines to give any other name) says he experimented with “play piercing” as young as age 10 by attaching safety pins to his body and then removing them. Today, Lifto has 11 permanent body piercings; in his act, he lifts heavy objects from rings in his pierced parts.

Lifto, 25, formerly sold car insurance to support himself while he tried, unsuccessfully, to get bookings. Now, thanks to Rose, Lifto is moderately famous back in his hometown of Port Angeles, Wash. “My mom saw me on Sally Jessy Raphael,” he says.

Tim Cridland, the Torture King (formerly known as the Human Pincushion), also says he became fascinated with altering his body when he was a child growing up in Pullman, Wash. Now 28, Cridland says he taught himself the pain-defying tricks of the Indian yogi. But he never got much encouragement. He was working as a theater projectionist when Rose gave him his start.

“The Torture King is becoming a real star because he’s so well rounded,” Rose says. “He does this full human pincushion (corsage pins are stuck into his body), but he also walks up a ladder of sharp swords barefoot, and he eats glass light bulbs.”

By bringing artists such as Mr. Lifto and the Torture King to young audiences across America, Rose says he is helping to stave off the ultimate demise of a cultural tradition. “When all the freak shows are gone, we will have lost a piece of Americana, and a lot of super-specialized knowledge,” he says. “Where are you going to go to learn how to swallow a sword when we’re gone?”

*

The word freak has long been associated with physical deformity and disability, says Tom Compton, a Berkeley writer and historian specializing in attitudes toward disability. “While the freak show may have gone away for a while, the fascination with physically different people never has,” Compton says. “I think it goes back to prehistory--that fascination or fear.”

Rose is capitalizing on the symbolic and shock value of the word freak . Yet most of his troupe are not “born freaks,” as they call them in the circus, but “made freaks”--people who have intentionally altered or mutilated their bodies. His only “legitimate born freak,” Rose says, is Dolly the Doll Lady, a dwarf who toured with the Mills Brothers Circus in the 1940s and had been long retired when she joined Rose’s troupe.

As his renown has grown, Rose has had to confront some touchy issues raised by the freak-show concept. The sideshow leader has been criticized for having Dolly in the show--a complaint that clearly vexes him.

“When we put Dolly back to work, her kids called and said we’d added years to her life,” he says, defending the decision. (Dolly did not go along on the Lollapalooza tour, Rose says, because traveling on band buses would be uncomfortable at her age--63.)

Just a few months ago, Rose was talking about possible additions to the sideshow, such as a bearded lady from New Mexico. But now, because of the criticism, he is backing off.

When traveling shows began to die out in the 1930s and ‘40s, freaks and freakishness were co-opted by writers and artists as symbols of estrangement and alienation. They show up in this guise in Tod Browning’s 1932 cult classic film “Freaks,” in Diane Arbus’ photographs of midgets and giants, and--most recently--in the Jim Rose Circus Sideshow. The show suggests that alienation is cool, and that is clearly one reason young people flock to see it.

Yet some people feel using freaks as symbols and icons is “demeaning to people who are different,” says Compton, the Berkeley writer and historian. The popularity of Rose’s sideshow reflects “a subconscious anti-disability, anti-deformity bias that has become part of the mind-set of Western culture,” he says.

Perhaps the best-loved artistic rendering of deformity in recent times is Katherine Dunn’s 1989 novel, “Geek Love.” In it, a woman adored by aficionados of the bizarre ingests insecticides and radioactive substances to produce mutant children who will perform in a sideshow operated by the woman and her husband.

Dunn, who lives in Portland, Ore., met Rose recently at one of Dunn’s readings, and the two became instant friends and mutual boosters. Dunn has seen the show seven times, and Rose is teaching her to eat fire.

“This guy (Rose) is not simple, and what he’s doing is very scary and very dangerous,” Dunn says.

“We’re living in a high-tech world,” she adds. “So much of our stimulus and entertainment comes from things that are quite abstract and disembodied. But the Jim Rose Circus is the real McCoy. Every person in the audience is empathizing with the people onstage.

It’s easiest to empathize with the performers up close. Fans who secure the coveted front-row spots at Rose’s shows see the tears in Lifto’s eyes when he slips a coat hanger through his pierced tongue and hangs his jacket on the hanger.

All this is “not necessarily pretty,” Dunn admits, “but it is wonderful, because it genuinely causes the mind to wonder.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.