Support Dwindles as Canada Votes in Unity Test : Amendments: Negative outcome on constitutional referendum could mean nothing--or eventual breakup.

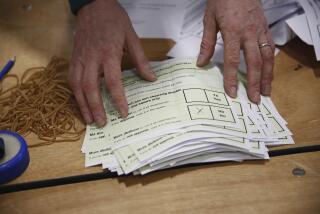

TORONTO — Canadian voters will go to the polls today to vote on whether their national constitution should be amended according to a sweeping set of proposals written in hopes of keeping the country united.

This is the first time Canada has held a nationwide referendum in half a century, and emotions are running high. One recent opinion survey found that 87% of adult Canadians are planning to vote.

Legally, the referendum is non-binding. But as a matter of practice, no Canadian politician will be able to overlook whatever signal the public sends.

The consequences of a no vote are not easy to predict. Some analysts say a no would mean business as usual for Canada, while others go so far as to say it would set in motion the eventual dissolution of the country.

A yes vote would be more straightforward: It would mean Canada’s leaders can proceed with the lengthy and cumbersome process of ratifying the amendments.

If the proposed amendments are ultimately ratified, they would set Quebec aside as a “distinct society” within Canada; reform Canada’s discredited Senate; give Quebec a permanent 25% representation in the House of Commons, even if its population declines, and grant Indians and Inuit--as the Eskimos prefer to be called--the right to govern themselves.

When the amendments were unveiled in August, Canadians seemed inclined to accept them. Increasingly, however, support has dwindled, and opinion surveys now show the amendments in serious trouble in the provinces of Quebec, British Columbia and Alberta.

Many Quebec French-speakers say they will vote no today because they think the amendments do not give enough power to their province. English-speakers in the west, meanwhile, are saying they will vote no because they believe the amendments give Quebec too much power.

There are a number of other divisions among Canadians over other elements of the package.

Organized feminists, for instance, oppose the amendments because they believe the constitutional changes could undermine the government’s commitment to women’s rights.

Some Indian chiefs complain that the proposals for native self-government are not explicit enough. Champions of Senate reform think the new Senate would still be ineffectual.

A large number of Canadians don’t really object to the amendments but plan to vote no simply because they are fed up with mainstream politicians and their seemingly endless attempts to amend the constitution.

People in the last category think their angry no votes will scare the political elite into abandoning constitutional tinkering for good and attending instead to the pressing economic problems now facing the country.

But their expectations contrast sharply with those of the Quebec no voters, who tend to think that if they reject this package of constitutional amendments, the English-speaking politicians will go back to the bargaining table and draw up a new deal that’s better for Quebec. For all the worry about Canada unraveling, polls suggest that what most Quebecers want is more autonomy within Canada--not outright independence.

The only sure outcome of a no vote would be a period of political uncertainty for Canada. In Ottawa, all three major political parties have been enthusiastically campaigning for the yes side. A no would show them to be woefully out of step with their own constituents and send them scrambling for new party lines.

And a no could lend tremendous momentum to several small regionally based upstart parties whose leaders have been fighting the amendments. The main beneficiaries are likely to be the anti-Establishment, western-based Reform Party, which opposes such policies as official bilingualism, and the Quebec-based Bloc Quebecois, which supports independence.

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney is required to call a national election by the fall of 1993, and the once-fringe Reform Party and Bloc Quebecois could end up with significant representation in the new House of Commons.

A no vote would unquestionably damage Mulroney, a prime minister who has had close and productive ties with Presidents Ronald Reagan and George Bush but who has thoroughly antagonized Canadians. Many constitution-weary Canadians blame Mulroney for forcing the whole painful, divisive issue of constitutional reform upon the country in the first place.

Canada’s current constitution dates only to 1982, when the nation was “patriated” from Britain. At the time of patriation, Quebec had a sovereigntist Parti Quebecois government, whose premier bitterly denounced the new constitution.

Time has passed and the political players have changed, but attitudes remain largely the same in Canada. Mulroney’s first attempt at coaxing Quebec to sign the constitution, a package of amendments called the Meech Lake Accord, died in 1990 when two English-speaking provinces rebelled against it.

That, in turn, incited a wave of resentment and pro-sovereignty feeling in Quebec.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.