Who Is Considered Rich? It’s the $100,000 Question

Being rich, it seems, is not what it used to be.

Once upon a time, wealth meant a lifestyle of leisure, luxury and protection from the hassles of everyday survival.

But these days, what it takes to qualify is a $100,000 household income, President Clinton says. And as elites go, that makes for a rather large club--a projected 5.8 million families in 1994, many with two adult members who hustle at full-time jobs.

“If you begin to describe these folks, they look a lot like the ‘Leave it to Beaver’ family--but where the wife went back to work,” said David W. Stewart, a USC professor of marketing.

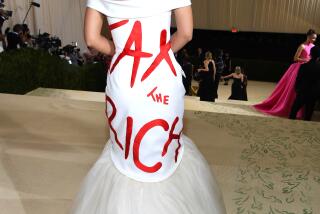

As Clinton takes on the make-or-break challenge of lobbying the nation to support a program based on rising tax burdens, a key selling point is that he seeks the heaviest payment from the wealthiest Americans. Families earning more than $100,000 a year will shoulder 70% of the new taxes he proposes, Clinton declared earlier this week.

The comment, in a nationally televised speech, set off alarm bells in many living rooms because Clinton had previously cited $200,000 as the threshold for higher taxes. White House aides later explained that income taxes would go up for families with adjusted gross incomes of $180,000 or more; the lower, $100,000 standard referred to other tax proposals, such as plans affecting energy costs and Social Security benefits.

In any case, the President has spotlighted the question of who is rich and who is not. It is fundamental to his notion of fairness in sacrifice and his goal of narrowing the gap between rich and poor, which has widened in recent years.

But the definition is very much in the eyes of the beholder: Those at the lower end of Clinton’s elite hardly consider themselves wealthy, whereas those who take home far less have little doubt about who is rich.

A $100,000 income “sounds like he’s talking about the rich--but that amount is a drop in the bucket for the rich,” said Maurice Zeitlin, a professor of sociology at UCLA. “The rich pick up $100,000 in a week.”

Nonetheless, families with incomes in excess of $100,000 are members of an exclusive club by some important measures. The 5.8 million that will belong in 1994 are a tiny 5.3% of all families, the Congressional Budget Office says.

As a group their occupants are highly educated, often middle-aged and typically hard-scrambling members of what might be considered a white-collar working class. Frequently, wives and husbands both hold jobs. About 3.2 million of these households had two or more wage earners, 1990 census figures show.

“Yes, $100,000 sounds like a lot of money and it is,” Stewart said. “But it’s not difficult for two professionals, a husband and wife, to earn that money together. They work 40 or 50 hours a week each and would not regard themselves as wealthy.”

A $100,000-plus income dwarfs the average U.S. household income of $31,889 (a 1990 figure) and purchases a lifestyle that most of the world can only envy. Yet clearly, today’s phenomenon of two-career households with high earnings, high debt and higher stress is a marked contrast to yesterday’s vision of true wealth--a vision that suggested shelter from the daily grind faced by the masses.

Social scientists point out, however, that the strain faced by many two-earner families is a consequence of lifestyle choices. Nobody, after all, made them pay for extravagant homes, private-school tuition or fancy cars.

Thus, protests that Clinton is asking too much of these families are likely to be greeted cynically by the much larger public, which envies their salaries and their luxuries and even their complaints.

“These are all choices that lower-income people don’t have,” Zeitlin said.

Figuring out who really is wealthy is further complicated by regional differences in the cost of living, particularly the cost of housing.

Census analyses show, for instance, that the ranks of six-figure earners are more crowded on the West Coast and in New England, where houses cost more than in the Deep South or Midwest.

But if the proliferation of two-earner families has made it harder to define who is rich, the gradual rise in American living standards has made it all but impossible to define the boundaries of the middle class.

“You’re speaking about a group that spans from blue-collar to professional and managerial classes,” said Mark Baldassare, a professor of urban planning at UC Irvine.

The political consequences for Clinton of asking more sacrifice from the well-to-do are not immediately clear. George Bush outpolled Clinton among affluent voters, exit polls showed.

Bush, for example, got only 29% of the vote from those earning less than $20,000, but 46% of the vote from those earning $75,000 or more a year, according to Los Angeles Times exit poll data from the presidential election.

Clinton, by contrast, gained just 38% of the vote of those living in households with total incomes of $75,000 or more. He did much better among struggling voters, getting 53% of the ballots of those earning less than $20,000.

As a result, some say the political symbolism of taxing the affluent could work well for Clinton--whether or not families earning $100,000 a year are truly rich.

“Ninety-five percent of us will look at it and say, ‘Great--he wants to tax the other guy and not me,’ ” Zeitlin said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.