Serrano Losing Grip on Guatemala : Central America: His offer of a referendum is rejected. Opposition leaders demand his resignation.

GUATEMALA CITY — Amid the first public signs that his military support is wavering, an increasingly isolated President Jorge Serrano appeared Sunday to be losing his grip on power after an offer to hold a referendum was soundly rejected.

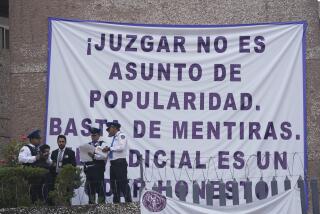

Within five days after he suspended the constitution, dissolved Congress and the Supreme Court and muzzled the press, the Guatemalan president has been thwarted in his efforts to consolidate power and stunned by a backlash of harsh criticism.

Serrano’s offer of a referendum--a rollback from an original plan to hold elections--was rejected by opposition leaders, who stepped up demands he resign.

“He is fighting for his life as president,” said a high-ranking diplomat participating in talks between Serrano and the Organization of American States.

“They’re starting to realize they didn’t measure the weight of international opinion very well. He is realizing he has no real support. His ability to negotiate is weakening every hour.”

An OAS delegation, led by Secretary General Joao Baena Soares, is in Guatemala to urge Serrano to restore democracy. The delegation met with the president for two hours Saturday night and with military commanders, members of the dissolved Congress and other Guatemalans on Sunday.

Serrano, who seized absolute power Tuesday, claimed he was acting to rid government institutions of corruption. His opponents claim he is as corrupt as any of the legislators and judges he deposed.

With diplomatic activity intensifying, the high command of Guatemala’s armed forces met for about 90 minutes with the OAS delegation. The officers were warned of the likelihood of sanctions or more drastic punishment from the international community, according to a source involved in the talks.

Emerging from the meeting, the defense minister, Maj. Gen. Jose Garcia Samayoa, seemed to be backing away from earlier support for Serrano and for the first time avoided endorsing the president’s actions.

“These kinds of meetings are what will give us the path, the solutions, so that we can make suggestions to the citizen president,” Garcia Samayoa said.

“This (international pressure) should worry us, and we should be very respectful of them (the elements applying pressure).”

The military is reported to be divided over support for Serrano. The defense minister and the president’s military chief of staff are believed to have backed Serrano, while the military intelligence service and one of two brigades based in Guatemala City opposed the president, according to a source familiar with the armed forces.

If Serrano is to be forced out of office or at least made to restore Congress and the Supreme Court, military approval and perhaps action is crucial, analysts say. From hiding, congressional leaders last week asked the army to oust Serrano--a petition that the president said disturbed him.

“I want to tell you I feel sad to see some civilians now wanting to provoke the military in an act for which they are not responsible,” Serrano said in a televised speech Saturday night. “The problem of corruption is a civilian problem.”

In the same speech, Serrano said he would hold a plebiscite within 90 days to seek approval for a series of constitutional reforms he plans. He was forced to make the offer after the highly regarded Supreme Electoral Tribunal blocked his original plan to hold an election for a constituent assembly--a step that Serrano needed to reinforce his own legitimacy but that many diplomats said would have been a sham.

“As long as the constitution is suspended, completely or partly, no elections can be held,” said Arturo Herbruger, president of the five-member tribunal, which voted unanimously to forbid an emergency-rule election.

The plebiscite proposal was dismissed out of hand by opposition leaders as a ploy, offered by the president as he grapples with an unprecedented groundswell of opposition that has united groups as diverse as Guatemala’s powerful right-wing business elite and indigenous peasant organizations.

The referendum, Serrano said, would also be used to submit for public approval a transition plan that would include election of a new Congress.

By focusing on Congress, Serrano hoped to capitalize on widespread public disapproval of the country’s 116 legislators, many of whom are seen as corrupt influence-peddlers.

Ramiro De Leon Carpio, Guatemala’s human rights ombudsman, joined a growing call for Serrano to resign. A frequent government critic, De Leon Carpio has been in hiding since the coup.

“Serrano has put the country into a hole from which there is no easy constitutional way out,” he said. “The only solution is for Serrano to resign.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.