Standing by Their ‘Hood : Residents of South-Central’s 74th Street Say Their United Community Has a Bad Rap

Kids, crack addicts and struggling single moms.

Government workers and community activists.

They are among the many who make up the urban mix of residents on 74th Street in South-Central Los Angeles.

But 74th Street residents are angered that their neighborhood is often portrayed as a “bad part of town,” plagued by gangs and drive-by shootings. Outsiders don’t know about the block club formed last year to unite the street’s residents.

They don’t know that 74th has its own personality: a street lined with modest houses and well-kept front yards, some fenced in with wrought-iron gates. Children ride their bikes during the day. In the evenings, folks enjoy the cool breeze while sitting on their porches. And during the summer, a block party brings everyone out to celebrate their community.

The people on 74th have lived through the turmoil of the rioting at Florence and Normandie--only blocks away--that followed the Rodney King police brutality trial in the spring of 1992.

They are also proud. Today, they are trying to rebuild their community and their lives in this diverse neighborhood, which has gone through many changes.

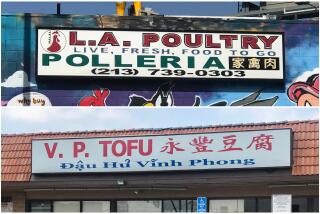

Once a predominantly Anglo neighborhood, 74th and the surrounding area is home mostly to African-Americans and Latinos. Korean-Americans own many businesses in the area but don’t live here.

Many of the residents on 74th have lived here their entire lives. Others are newcomers, adding to the mix of cultures, voices and stories.

*

Denise Wallick, 38, has lived on 74th Street since 1962. She’s a mother of four, a bus driver for the transit district and president of the street’s block club.

*

“When my parents and I first moved to the block, there was only one other black family here. The rest were white. Now there’s only one white family on the block. They’ve been on this street longer than anyone else.

More and more Hispanics are moving in. It seems like they’re taking over the neighborhood just like blacks did in the ‘60s.

Right now, there are about four Hispanic families on this street. I think that’s enough. I really don’t want the block filled with them, but I wouldn’t move out over it. Besides, they’re here and I feel we should get to know them and treat them like neighbors.

I’ve seen a lot of things change around here, but it really changed in ’92. After the riots we united. We came together and formed the block club.

We figured since we have to live together, we should all get along. We needed to start looking out for each other.

Even though our block club was formed because of the riots, I was still very angry when I saw my community burning.

I feel if you don’t like Korean stores, go shop somewhere else. But don’t burn them. If you do, they can collect fire insurance and rebuild right back in the same place. But if you stop shopping there, they lose money and eventually move or go out of business.

All in all, I feel like our street isn’t that bad. We can sit outside and not have to worry about anything bad happening.”

*

Veeondra Ward, 19, is a single mother of one. Three years ago, her 17-year-old fiance was fatally shot outside a nightclub. She works as a data processor and attends Los Angeles Southwest College.

*

“My neighborhood hasn’t prevented me from being successful, but I want to live in an area where gunshots and police helicopters aren’t the norm .

Where you live can’t constitute how your life will turn out. That’s up to the individual. My mother raised four kids all by herself. She was our mother and father. From her, I learned all my morals and values. She made me strive to be somebody.

A lot of black males from my generation aren’t being fathers to their children because their fathers weren’t there for them. They didn’t have anyone to teach them how to be a man.

People are in gangs and drugs because they’ve given up on life. They think that’s the best they can do.

I don’t think the negative stereotype the media has handed South-Central is accurate. They make the gangbangers the stars. They don’t mention the centers and programs we have going on here, like the block club and things of that sort.

I would like to see peace in the neighborhood. More unity. People to mingle more. We need to stick together.

I don’t want to raise my daughter in this community. But if I have to, I will. No matter what, my daughter and I are gonna make it.”

*

Juan Ruiz, 34, is from Nicaragua. He has lived on the street for almost two years and is a member of the street’s block club.

*

“I fear for my family. The fear’s not caused by my neighbors on this street. My street is OK. It’s caused by the larger streets that surround my block. That’s where a lot of the problems are. If there are any problems on my street, it is mostly caused by outsiders.

This is not where I want to raise my kids. This is only temporary. They have to go to school and my wife has to go to work. It’s not safe on the streets.

Before the riots, I didn’t have fear. During the riots, I looked around and I saw my own race looting and destroying our community. It made me feel ashamed to see my own people doing that.

The riots made me ask myself, “What kind of world do we live in?” People were looting and burning freely.

Now people are angry for what happened to them, and I fear that they may try to take their anger out on another race.

I would like our community to be like the white communities. I would like cleaner streets, a safer environment. We pay taxes just like they do.

Since I’ve lived here, I haven’t experienced any culture clashes. I get along with everyone.”

*

Glinda Hamilton, 44, is a letter carrier for the U.S. Postal Service. She’s lived on 74th for 13 years, has been happily married for 25 years and is the mother of two daughters.

*

“We have our share of negative people. We have our drug addicts and gangbangers. But there’s also a lot of good, hard-working people out here trying to make it and provide for their families.

A few weeks ago, my tree fell down in front of my house. It was blocking my driveway. The president of the block club gave me a phone number and after enough persistence, city workers came in and took care of it. Before the riots, that would’ve never happened.

I was agitated and angered by the riots. The riots not only damaged the community, it brought the property value down. I’m a homeowner and that was another concern for me.

I couldn’t understand how people could do that to their own neighborhood. A lot of the looters weren’t doing it for the cause (of civil rights). The police took too long to come so (looters) seized the opportunity to get some material gain.

The riots weren’t a good thing, but in my 13 years here on this street, I’ve never seen as much togetherness as I did after it happened. It brought us closer as a people. It made us care and look out for each other.”

*

Damian Lamont Green, a 12-year-old seventh-grader, has lived on 74th Street for one year.

*

“This street’s not bad. But I don’t like the gangbangers. I don’t like the way they treat people or the way they act.

I don’t live with my mother and father. My grandfather raised me. I still live with him. He’s 72.

Sometimes I get A’s in school and sometimes I get C’s. I do schoolwork to stay out of trouble. I have some good friends and some bad.

I’ve thought about being in a gang, but I don’t want to do that. I’m afraid to be killed and I don’t want to do that with my life. I want to be an engineer.”

*

Joshua Lindsey, 11, has lived on 74th most of his young life. The sixth-grader attends a private school .

*

“Do I live in a bad neighborhood? No.

There’s more to South-Central than gangs. We have respectful people here. People help each other. They watch out for each other.”

*

Dallas Epkins, 8, who lives in Ventura County, often visits his grandfather, a resident of 74th for the past two years.

*

“I see a lot of drinking here. I don’t think it’s a bad neighborhood. I just think they should stop doing what they’re doing.

It’s OK here, but I like where I live better. My neighborhood is quieter and there’s not that much violence going on there.”

*

Anthony, 29, says he is a crack user who contracted multiple sclerosis 10 years ago. He has lived on 74th for more than 20 years.

*

“If I were in a different area, I wouldn’t be doing what I do now. I smoke marijuana and crack cocaine. I don’t rob. I don’t steal. I hustle, I wash cars and cut grass.

My average day is like this: I wake up and thank the Lord. I eat my breakfast, go out, get my little weed and smoke my little weed and get me some beer. The crack ain’t an everyday thing.

I gotta get out of this neighborhood.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.