COLUMN ONE : Chasing the Mysteries of Life : After you have helped crack the code for DNA, what’s next? At 77, Francis Crick--scientific free spirit--says he is on to something even bigger.

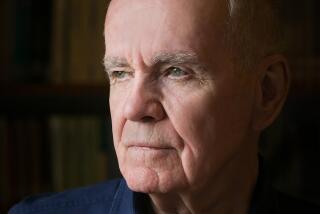

The man who discovered the secret of life is having his makeup done. He tolerates it with good humor, like the proper British gentleman that he is.

Francis Harry Compton Crick smoothes his wispy white locks as the television makeup artist brushes his face with peach-colored powder, evening the tone of his perpetually ruddy cheeks. “The thing that I have to watch,” he says, recalling an earlier admonition from his wife, Odile, “is that my tie is straight, and that this side of my hair doesn’t stick out. My wife cuts my hair.”

This is a rare step into the spotlight for Crick, one of the world’s most renowned, most publicity-shy--and most free-spirited--scientists.

The secret of life, by the way, is DNA. Forty-one years ago, Crick and James Watson cracked the code for this mysterious molecule of heredity. Their story is a scientific legend: Two young men--Crick, then 36, and Watson, a mere 24--made the most significant contribution to biology since Darwin’s theory of evolution and earned a Nobel Prize. All with an article just 900 words long.

The discovery that DNA is built like a double helix was nothing short of revolutionary. It has filtered into every aspect of modern life, spawning an entire industry (biotechnology) and prompting raging ethical debates about the perils of genetic tinkering.

DNA is ubiquitous. It is in the courts, where DNA “fingerprints” can set the innocent free. It is in the supermarket, where designer tomatoes are for sale. It is in the operating room, where doctors insert healthy genes into sick people. It is in the bedroom, where couples scrutinize their genetic histories in deciding whether to have a baby.

And now, at age 77, the adventuresome scientist who helped bring about this revolution is off on another jaunt.

This time, Crick’s journey takes him to the realm of neuroscience, where he is attempting to piece together a puzzle far more complicated than DNA: the workings of the human brain. (He has already tried to tackle the origin of life on Earth and the meaning of dreams.) In a field where most scientists are knee-deep in the minutiae of this receptor or that neuron, Crick is the big-picture guy, seeking to answer the unanswerable: What is the root of human consciousness?

And so what if he wanders off into philosophy and religion, or if some of his ideas are a bit wacky?

He’s Crick. He can say what he wants.

These days, Crick is doing more talking than usual, which accounts for the rare TV appearance. After four decades of refusing to grant interviews, he is reluctantly on a media tour--a handful of 90-minute chats with America’s top publications and a few public television interviews (hardly Oprah or Geraldo) to promote his new book. In it, he attempts to do for the study of the brain what the double helix did for DNA--lay out a basic theory that those who come after him may prove.

It has not escaped his notice that, at his age, he may not live long enough to find out whether he is correct.

“Well, of course I have asked myself that question,” he confesses in his impeccable accent, over a room service lunch at the Century Plaza Hotel. “It may turn out that one is looking at it quite from the wrong point of view, and everybody will say, ‘Poor chap, when he went into a new field, he couldn’t do it again.’ ”

A Full-Time Thinker

As a research professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, Crick is not a typical scientist in that he does not maintain a “wet lab”--meaning he does not do experiments. Nor has he ever been a full-time university professor, with the exception of a short stint at Harvard.

Rather, Crick is a theoretician. What he does is think.

“He invites people to stay with him a week, a month or sometimes several months,” said Christof Koch, a Caltech neuroscientist and Crick’s collaborator for seven years. “And then there’s this very intensive period where you talk with him all day and evening and then you go out and socialize and talk about science. It’s a very unique working style.”

It is also a style that only someone of Crick’s stature could get away with. And whether his theories prove correct seems to matter less to him than that they are thought-provoking, and that he has fun dreaming them up. Once, a colleague of Crick’s asked his wife whether he works a lot. “No,” she replied. “I don’t think he works a lot. But he thinks a lot.”

Crick does not see anything extraordinary in what he does. “I don’t think it’s anything particularly virtuous on my part, it’s just that I have reached an age where I can do what I like. Not all scientists can.” Besides, he added, doing experiments is “more expensive than just sitting and thinking.”

Such self-deprecating repartee is a hallmark of any conversation with Crick. His blue eyes, shielded by unruly white eyebrows, dance as he speaks, revealing more than a hint of mischief. He seems to enjoy amusing himself, both at work and at home. He drives a white Mercedes with the license plate ATCG--the initials of the four chemical base pairs that compose the structure of DNA. It tickles him when the garage mechanics get the joke.

“He has a real charm . . . He’s sexy,” said his longtime secretary, Maria Lang. “I mean, he has this energy, a magnetism.”

It is this energy that prompts often reticent scientists to share their thoughts and findings with Crick, which serves him well as he cruises the cerebral landscape.

Crick performs an unusual function in neuroscience. David Hubel, a Harvard University neurobiologist who has his own Nobel Prize, describes him as “kind of a clearinghouse for ideas.” He picks the brains of the nation’s top minds and, in his own brilliant way, synthesizes their ideas into novel theories of his own. “He has very good taste in the people that he picks out to talk to,” Hubel said. “People are always delighted to talk to Francis.”

In the ordinarily cautious world of science, where nothing is accepted as true until experiments have proved it so, Crick does not hesitate to go out on a limb. “He’s got a very free-ranging mind,” said neuroscientist Bill Newsome of Stanford University, “and he’s not afraid to talk about what’s on his mind.”

Said Hubel, a bit more bluntly: “Sometimes his ideas seem to be off the wall, and other times his ideas are terrific.”

Astonishing Hypotheses

Off the wall or not, people listen.

About a decade ago, Crick joined those trying to debunk the classic Freudian theory that dreams have a deep psychological meaning. Dreams, he suggested, have little significance at all. Rather, he argued, they play the role of mental housecleaner, reorganizing the brain in the middle of the night so that the memory can store information more efficiently. The theory has not been proved, but nonetheless it made news--if only because Crick proposed it.

In 1981, Crick weighed in with his version of the origin of life. He and a colleague at the Salk Institute wrote a book proposing that life began when microorganisms from another planet were dropped here from a spaceship sent to Earth by a higher civilization. They called this theory “directed panspermia”; panspermia means “seeds everywhere.”

“I decided I would like to write a book about the origin of life,” Crick said. “Most people think it’s something spiritual. No! It’s much worse than that! It’s chemical! Most people, you must have noticed, hate chemistry. So you have to find some way of discussing what is basically a chemical problem without burdening them with the chemistry.”

The result was directed panspermia--a far-out notion Crick says he is not wedded to. But the book, “Life Itself,” was a kick to write, a fun adventure with just enough scientific footing--and Crick as its author--to get it taken seriously.

“It’s just a theory,” he said. “People seemed to think that I was a fanatical believer. . . . There was a lot of reaction to the idea from people who didn’t actually read the book who think that I must have gone a bit soft in the head.”

Crick’s current book is a tad less far-fetched, though it is creating ripples just the same. It is called “The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul.” (He picked the name; it’s kind of catchy, if he does say so himself.) If the cover is any indication of the relative importance of topic and author, Crick’s name is at the top, in much bigger print than the title.

“The Astonishing Hypothesis,” Crick writes, “is that ‘You,’ your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules. As Lewis Carroll’s Alice might have phrased it: ‘You’re nothing but a pack of neurons.’ ”

Critics have suggested that the hypothesis is not really all that astonishing--at least not to neuroscientists, who generally accept it as true. Crick agrees, but says he wants to convince the public that brain chemistry--as opposed to some intangible divine spark from God--is responsible for human thought, character and free will.

So he uses the book to take potshots at two of his favorite targets.

“Philosophers have had such a poor record over the last 2,000 years that they would do better to show a certain modesty rather than the lofty superiority that they usually display,” Crick writes. “The record of religious beliefs in explaining scientific phenomena has been so poor in the past that there is little reason to believe that the conventional religions will do much better in the future.”

Skewering philosophy and religion in a book that is supposed to be about the study of the brain might be awkward for other scientists. But Crick pulls it off, and incorporates the nitty-gritty of science to boot. Crick and Koch--to whom the book is dedicated--believe that vision is a logical starting point for studying the brain. The latter part of the book is devoted to experiments that Crick says might help researchers learn more about the way neurons interact to create sight.

Although most colleagues give Crick high marks for doing his homework, some see him as sort of an odd duck outsider whose work is of little relevance to what goes on in the lab. In the tight-knit fraternity of science, of course, this is not openly admitted--not, at least, for publication.

“Hard-core laboratory people have a tendency to think, ‘Here’s an old man who was bored with molecular biology and tried to do another big stunt in neuroscience and it really didn’t work out,’ ” said Franz Hefti, a USC professor who is also director of neuroscience at Genentech, a biotechnology firm.

“But,” Hefti added quickly, “that would not be my opinion. I think neuroscience has a need for strong thinkers. Is running to the lab each morning and working on some tiny protein in the brain really making a contribution to our understanding of human consciousness?”

The Road Less Traveled

In a sense, Crick faces the dilemma that every Nobel laureate must face: What do you do after you’ve done it all? It is a problem made all the more burdensome by the fame, at least within scientific circles, that the Nobel brings. As Andre Lwoff, who won the 1965 Nobel Prize for medicine, once lamented: “We have gone from zero to the condition of movie stars.”

Different people respond in different ways. The names Watson and Crick are as intertwined in molecular biology as Laurel and Hardy are in comedy. But the two could not have chosen more different post-Nobel paths.

Watson wrote a book, “The Double Helix”--a breezy, insider’s account of the race to beat out famed chemist Linus Pauling in decoding DNA. It was an instant bestseller, but it was published over Crick’s protestations; he thought it a tad unseemly, and not scholarly enough to be published by the Harvard University Press.

The book was as much about scientific pursuits as it was about the personal adventures of this odd couple--Watson, an American with an appetite for tennis, champagne and ogling young women, and Crick, a charming (and married) conversationalist who spent World War II doing the mundane work of developing torpedoes for the Royal Navy.

And few could forget Watson’s famous opening line: “I have never seen Francis Crick in a modest mood.” (Says Crick now: “I think, apart from this curious opening sentence, I come out rather well in the book. I think he had the wrong word. I think he wanted to say ‘in a lively mood.’ ”)

Watson remained in molecular biology, although he is no longer a working scientist. For more than a quarter-century, he has directed the respected Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island. And as the first director of the Human Genome project, an ambitious effort to map the entire genetic blueprint of the human body, he was smack in the center of the DNA revolution. He is now on sabbatical in England, writing his autobiography.

Crick, meanwhile, has watched from the sidelines as genetic research exploded. As a result of his and Watson’s work, scientists are pinpointing genes for new diseases with such alacrity that they joke about the “gene of the week.” Yet the man who some have called “the grandfather of molecular biology” says he does not regret leaving it all behind--even as others capitalized on his discovery, striking it rich in biotechnology.

Although he does not consider himself wealthy, Crick and his wife of 44 years travel often, and have two homes--one in La Jolla and another in Borrego Springs. It is a long way from Crick’s starving student days, when they shared a tiny flat next door to a pawnbroker. “When things got tough financially,” he said, “we used to go and pawn the typewriter.”

The one thing Crick never wanted to be was a celebrity. He is not. For many, his name is but a fuzzy memory from some high school biology class. Some might say this is a function of American society, of a culture that puts actors and sports stars--not scientists--on the covers of its magazines.

But it is also a function of Crick himself. For 41 years he has gone to extraordinary lengths to keep himself out of the public eye.

Thus, requests for Crick’s time and attention have been uniformly declined with polite note cards. “Dr. Crick thanks you for your letter but regrets that he is unable to accept your kind invitation to . . . ,” the cards announce, followed by a checklist with the appropriate item marked off: send an autograph, provide a photograph, cure your disease, be interviewed, talk on the radio, appear on TV, etc. Crick’s secretary says keeping reporters away has been her most important job in the 17 years she has worked for him.

He does not accept honorary degrees--not even from Cambridge, which had hoped to fete Crick and Watson last year, upon the 40th anniversary of their famous discovery. Watson went. Crick stayed home.

He did make one exception to his no-awards rule, when the Queen of England bestowed on him the Order of Merit--an accolade one notch above knighthood and one below lordship. But that, he said, was only because his wife and his secretary insisted he not pass up a chance to meet the Queen.

Thus those who are close to Crick were, to borrow a word from the scientist himself, astonished that he agreed to do the book tour. The publicist says it has been a bit of a disaster: ice and snow cutting interviews short on the East Coast, an earthquake in California commanding reporters’ attention.

No matter to Crick. He is having a grand time. Today’s science journalists, he said, are smarter and far more interesting to talk to than those of the 1950s. And the East Coast was so cold he mostly stayed in his hotel, reading and writing instead of rushing about. Wonderfully restful. As to whether he is selling any books, he has not the foggiest idea.

He is looking forward to a bit of peace and quiet back in La Jolla, to a return to his garden and his daily swim. But 41 years after he earned a page in the history books, Francis Crick says he is finally getting used to the idea that people recognize his name.

Whether they will recognize it 41 years from now, for his contributions to neuroscience, is another matter. It is the one big question that does not seem to weigh on the mind of the man who discovered the secret of life.

A Brief History

* Name: Francis Harry Compton Crick

* Born: June 8, 1916, Northampton, England, to Harry Crick, a shoe factory owner and his wife, Anne Elizabeth (Watkins) Crick.

* First experiments: Tried--and failed--to make artificial silk at home at age 10 or 12. Put an explosive mixture into bottles and blew them up electrically, prompting parental order that no bottles would be blown up unless they were immersed in a pail of water.

* Early honors: Awarded a book on insect-eating plants after collecting more species of wildflowers than any other schoolboy in town. Made the high school tennis team.

* Later honors: Shared the Nobel Prize for medicine, 1962, for discovering the double helix structure of DNA in 1953. “We were lucky with DNA. Like America, it was just waiting to be discovered.”

* Education: Bachelor of science, University College, London, 1937. Studies interrupted by World War II and work as a military physicist. Ph.D., Cambridge University, England, 1954. “I’m one of the few people who got a Nobel prize for work done before they got their Ph.D.”

* Occupation: Molecular biologist, neuroscientist, big picture thinker.

* Day job: Research professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

* Personal: Married to Odile (Speed) Crick, an artist. Father of two daughters, Gabrielle and Jaqueline, and a son, Michael, from a previous marriage. Resides in La Jolla, remains a British citizen. “I don’t feel quite American yet. But I feel Californian.”