Masters Could Use an Attack

The Masters is a great and good sporting institution. I yield to no man in fondness for it. No way would I try to belittle it.

But, having said that, I wish to file a demurrer of sorts. It is this: I wish it were a little more vulnerable to attack. It is impregnable in its present form.

You see, on Sunday, I was kind of longing for someone to come roaring out of the pack, mount up a garrison finish--kind of like Johnny Miller firing that final-round 63 at Oakmont to win the 1973 U.S. Open.

But I knew it was impossible. Nobody was going to shoot a low, exciting number on that course. You could only hope one of the leaders would fire a high, exciting number. You knew that, if any of the leaders managed par or a little better, he was in. Pretty dull stuff. Playing for a tie, so to speak.

You have to laud what the Masters is trying to do. All sports are in the same predicament. They have to fight continually to preserve the integrity of their sport.

Take football. They tinker with it every couple of years, change the blocking alignment, move the hash marks, change the contact. Only this year, they had to bow to the blizzard of field goals that was taking away from the historic object of the game--to score touchdowns. They had to downgrade the field goal.

No sport is exempt. Pro basketball outlaws the zone defense. All basketball had to put in a shot clock; baskets count three points at long range, and the center jump that used to follow every basket now only opens a game.

It is the march of science that frustrates games, too. Track and field has the devil’s advocate role in stemming the use of steroids that make athletes run faster, jump higher, throw longer. Better times through chemistry is a constant bugaboo they have to fight off, to say nothing of the lawyers who seek to overthrow their authority and frustrate the illegality.

Golf’s nemesis is technology. You turn the metallurgists and physicists loose on the great game and, pretty soon, you’ll have a bag of tools that can shoot a 59 all by themselves. They’ll get square grooves, round grooves, oversized, hollow-backed implements you can’t hardly hit off line.

The U.S. Open tries to head them off at the pass by growing ankle-high barbed-wire rough and narrowing fairways till you have to proceed down them single file. So, these guys get clubs you could hit out of a haystack.

The Masters doesn’t have rough. So its main line of defense is the green. It takes its greens and tricks them up with undulations, slopes, peaks and valleys that defy reasoning. Almost gravity.

The putter, you see, is the one instrument they can’t make foolproof. Some years ago, hockey introduced the curved stick to increase scoring. But putting is not susceptible to technology at all. Putting is between the ears. It’s a function of nerves, not reflexes. Guys have won tournaments putting with a three-iron, to give you an idea.

So, that’s the Masters’ main line of defense. It makes the Maginot Line look like a sandcastle. It’s foolproof, the one part of the game the technicians can’t get at and overcome with a drawing board or an alloy. The brain is one part of the anatomy you can’t improve in a gym or weight room.

The Masters is diabolical. Some of its greens look from a distance invitingly flat. The pin seems to be cut in the middle, inviting the player to play below the hole. But what appears flat is really a 50% (or more) grade. If you are suckered into landing your ball below the hole, it will roll back off the surface and back onto the fairway, maybe back to your feet.

The Masters has other configurations that call for a putt to have to turn at right angles at the hole.

The first day of this year’s Masters, a lot of us were surprised to find the pins cut into what we have come to think of as “Sunday-afternoon locations.” These are spots on the green for the pin that are usually not brought into play until the last round, when they want to punish audacious players and make the winner agonize for his victory.

The greens were already so slippery, a polar bear would fall off. Veteran players had to try to squeeze the balls into the hole like toothpaste out of a tube. And longtime observers have never seen so many putts from great players come up short of the hole. Tom Kite, for instance, a U.S. Open winner, ended up so fearful of the hole that sometimes his second putt was short.

This preserved the integrity and dignity of Augusta National, but it had the effect of making the final round look more like a parade than a contest. A 69 was to win it. That might not make the cut on a regular tour tournament nowadays.

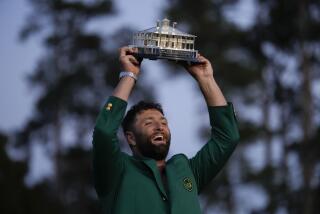

The 18th hole did not have a birdie all Sunday. Jose Maria Olazabal didn’t so much win the tournament as survive it. He often took the scenic route to the holes but, once there, he was the best at sinking putts that had to turn a corner to get in.

It’s not that a foreigner won our Masters. Shucks, Americans once won nine consecutive British Opens and 13 of 14, but nobody jumped off London Bridge.

It’s just that booby-trapped greens obviate that staple of the golf tournament, the late charge. We love the guy who comes riding to the rescue of the fort or the schoolmarm in the last reel. The chase is a staple of melodrama.

There was none at Augusta this year. It was like seeing a title fight that was all clinches, watching a Super Bowl with the last six minutes of falling on the ball, it was the golf equivalent of the four-corner offense.

They should cut the pins on ice floes the first few days to run the ribbon clerks out but make the course subject to attack on the final day. After all, we want to see the rousing finish; we like to see the champ able to go for a knockout. Who wants to see Dempsey have to jab, Ruth have to bunt their way to victory?

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.