Controversial Compromise Handcuffs Crime Bill Action : Congress: Black lawmakers, Clinton Administration, remain at odds over language of ‘racial justice’ measure.

WASHINGTON — The Clinton Administration is facing growing criticism of its inability to break an impasse over a controversial “racial justice” measure, which has paralyzed congressional action on the massive crime bill that the President had hoped to sign months ago.

Over the last several days, Administration officials have mounted a determined effort to broker a compromise with the Congressional Black Caucus over its demand to include the provision in the crime bill.

The measure would allow defendants in capital cases to challenge their sentences with statistics showing that the jurisdiction sentencing them had applied the death penalty proportionately more often to minorities than to whites.

But as Congress begins its July 4 recess, the Administration and the caucus have been unable to agree on language that the President could support--and the continued delay is generating rising unease among supporters of the crime legislation, which would pump approximately $30 billion into cities and states over six years to hire police, build and operate prisons and fund new crime prevention programs.

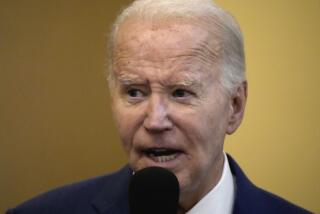

The Senate’s leading voice on crime legislation, Sen. Joseph R. Biden Jr. (D-Del.), said Friday that President Clinton must either declare exactly what version of the racial justice measure he would accept, or publicly demand its removal from the crime bill.

“The President has to say one of two things: ‘This is what I am for’ or ‘I’m not for any of it and I want it out,’ ” Biden said.

Likewise, Rep. Dave McCurdy (D-Okla.), a leader of House moderates, said Friday: “At some point the Administration has to bring this process to closure. . . . This is a progressive bill and to have this (dispute) hold it up is just nonsensical.”

So far, Clinton has been unwilling to make a clear public statement of his preference on the bitterly divisive measure, which narrowly passed the House but is strongly opposed in the Senate. Instead, the White House has privately tried to set in motion a process that could lead to resolution of the dispute shortly after Congress returns from its recess.

At a private White House meeting last week, the Administration agreed to seek a compromise with the caucus that Clinton would endorse, according to several congressional and Administration sources.

At that point, the caucus and civil rights groups supporting the idea would be given about two weeks to generate support for the measure in the Senate, the sources said.

If the Senate--which voted, 58 to 41, against the idea in an advisory vote in May--continued to resist, the supporters then would reassess, with the Administration’s clear hope that they would agree to drop the measure.

“I can’t imagine going ahead if it is going to be defeated,” said Rep. Don Edwards (D-San Jose), a principal sponsor of the measure.

But the deal has snagged at the first step: finding language to narrow the measure on which the Administration and the caucus can agree. “It is still a subject of negotiation,” said Rep. Kweisi Mfume (D-Md.), the principal negotiator for the caucus.

But many inside and outside the Administration are increasingly doubtful that any compromise can be reached that Clinton would accept. As a result, they are hinting that Clinton may soon do what he has been unwilling to do so far: publicly indicate that he believes the racial justice provision should be dropped rather than risk sinking the entire bill, now stalled in a House-Senate conference committee.

“That’s a judgment the President will make, and he is getting close to it,” said one senior White House official.

In the last few weeks, proponents have floated various compromises to narrow the racial justice measure. Among the ideas that have been discussed are stating directly that the bill would not require states to use racial quotas in applying the death penalty, permitting challenges only where defendants can prove a “pattern or practice” of racially discriminatory sentencing, and deleting explicit references to use of statistical evidence of alleged discrimination by defendants.

But groups representing prosecutors have rejected those ideas, insisting that they would not change the bill’s basic dynamic. Critics note, for instance, that even if the bill dropped the explicit reference to the use of statistical evidence, such evidence is the most common way to prove “a pattern or practice” of discrimination.

The long standoff over the racial justice provision has been wrapped in a fog of confusion and mixed signals. The single largest factor in the delay has been the Administration’s hesitancy and caution as it seeks to avoid alienating liberal and minority supporters of the legislation without opening Clinton to attacks from Republicans and prosecutors’ groups that the bill would essentially eliminate the death penalty.

“They thought they could get off the hook by having Congress make the decision for them and they wouldn’t have to alienate anybody,” McCurdy said.

Throughout the long legislative proceedings, the Administration has rarely spoken with a clear voice, other participants in the negotiations said. “I think they are split,” Biden said.

Indeed, some Administration officials, as well as key political advisers, have been leery of signing onto any formulation of the racial justice provision--which could leave Clinton open to GOP charges in 1996 of undercutting his support for the death penalty.

But other voices, like senior adviser George Stephanopoulos, have seconded the insistence of the House Democratic leadership that Clinton must make every effort to avoid alienating the Black Caucus and other liberals--whose votes the Administration will need in the fight over health care reform.

Looming over all these calculations, though, has been a conviction that senior Administration officials are only willing to voice privately: that there is no conceivable version of the racial justice provision that can attract the 60 Senate votes needed to break a near-certain Republican filibuster.

At the White House meeting last week, Biden and Senate Majority Leader George J. Mitchell (D-Me.) indicated that “it would be difficult to close to impossible,” to pass any version through the upper chamber, said one source who was present.

Rather than directly making that case to supporters of the racial justice measure, officials said the Administration has been hoping that they would finally come to the conclusion that the legislation cannot pass--and voluntarily abandon it rather than risk losing other provisions in the bill that they support, such as the $9 billion in new crime prevention programs for cities.

Administration officials insisted that they are making a good-faith effort to find common ground on the racial justice provision that the Senate can accept. But some House supporters said they believe that the exercise amounts to a pro forma effort designed primarily to deflect blame from the Administration if the Senate continues to resist the measure.

“They are setting themselves up to say ‘we couldn’t sell it,’ ” said one senior House staff member. “They don’t want to be the ones to say to the Congressional Black Caucus: ‘You can’t have what you want.’ ”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.