Crossing the Culture Line : Brick by Brick, the Walls Between Communities Are Beginning To Come Down as Activists Work To Translate Suspicion and Friction Into Empathy.

The first time Bong Hwan Kim met Karen Bass, they sat across the table from one another at Roscoe’s House of Chicken & Waffles at Manchester and Main in South-Central Los Angeles. It was January, 1992, more than two months before the riots.

Bass, executive director of the Community Coalition for Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment, was getting ready to launch a campaign against 15 liquor stores in South-Central, at least 10 of them Asian-owned. It was an issue that could easily disintegrate into traditional inter-ethnic politics. African Americans on one side, Korean Americans on the other. One group ravaged by the American system, another trying desperately to become a part of it. Bass wanted to prevent that polarization. She had heard that Kim, director of the Korean Youth and Community Center, was something of a renegade--independent from his Korean-born elders, who were determined to fend off any effort to infringe on the autonomy of the liquor-store owners. By agreeing to work together, the pair were neutralizing the liquor stores as a racial issue. The colors had begun to blur.

By the first week of May, however, they confronted more than the question of 15 problem stores. Some 200 South-Central businesses selling fortified wine and malt liquor burned to the ground in the aftermath of the Rodney King trial. As the fires raged, Bass and Kim talked by phone. Bass knew the neighborhood would fight the reopening of the liquor stores, and, again, she needed an ally in the Korean community. For Kim, the issue had become more troublesome. Korean-American liquor-store owners had been targeted, and they needed to be compensated. Bass agreed. Once again, they were trying to bridge the divide.

The informal alliance between Bass and Kim is an example of what is happening on a small but significant scale across ethnic Los Angeles. A few African-, Asian- and Latino-American leaders are declining to use the race card with one another or with the white minority. Divisive notions like “the new majority” send them into philosophical contortions. “It makes us sound like we’re going to be the new oppressors; we want to do something different--to change the paradigm of social interaction,” says Arturo Vargas, vice president of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund and a fellow consensus builder.

Brick by brick, leaders like Bass, Kim and Vargas are knocking down the walls that separate their communities. They get guidance, friendship and mentoring from others such as Ron Wakabayashi, the newly named executive director for the county’s Human Relations Commission; Joe Hicks, the executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference of Los Angeles, and Stewart Kwoh, president and executive director of the Asian Pacific American Legal Center.

“They are consciously straddling different worlds,” Xandra Kayden says of the members of these coalitions. “They are for their group but not against others.” In an article for The Times’ Opinion section last year, Kayden, a senior fellow at the Loyola Marymount Institute for Leadership Studies, wrote that, in the absence of a citywide consensus builder, Los Angeles has “translators”: articulate, usually young people whose task is to represent their group’s interests to the broader world.

But things tend to get lost in translation, and straddling two worlds can leave you without a foothold in either. Kim says Korean Americans need to be “new players in the game that will redefine race relations in America.” At the same time, he volunteers that people who share his vision of a multiculturally diverse but harmonious Los Angeles are still on the “lunatic fringe. Not only do we face possible repercussions from our own,” he adds, “but we still have to deal with the mainstream. There’s not many safe places for people like us.”

VISITORS TO THE COMMUNITY COALITION ON THE CORNER OF 85TH Street and Broadway must be buzzed in. Inside, Bass, in a flower-print dress, her Afro clipped short, wastes little time letting a reporter know where she stands. She pulls out an old issue of this magazine and opens it to a photo essay showing Korean-American store owners and their Latino and African-American customers. She points to a photo taken behind a counter. A young black boy, the manager’s son, is sitting on the Korean store owner’s lap. A rifle stands nearby. “Look at that gun. That kid could reach over and grab it,” she says. “We’re supposed to celebrate this?”

Bass, 40, was born in South Los Angeles. When she was 10, her father, a postal worker, and her mother, who’d owned a beauty parlor in Watts, moved to the Venice-Fairfax area so their children could attend better schools. There Bass watched whites “nearly fly out” as black families like hers moved in. She went on to study philosophy at San Diego State and then became a physician assistant. Along the way, she married a Chicano activist, had a child, got active in the anti-apartheid movement and continued working in civil rights and Latin American solidarity groups. She considered herself an “internationalist,” as comfortable in Latin America as she was in North America.

Bass divorced and ended up teaching health communication in USC School of Medicine’s physician assistants program. She’d planned to stay there, raising her daughter and restricting her activism to after-hours, but in the mid-1980s, her world was shattered by crack. “We’d been good on critiquing the War on Drugs,” she says of her activist friends, “but I’d never experienced anything like this. Coke crossed class and gender lines. I watched people all around me fall out.” When a close family member developed a crack habit, Bass decided she needed to learn more about addiction. She organized a conference on crack. Then, she says, “I did something I never thought I would do--I went after government funds to do organizing.” The U.S. Center for Substance Abuse Prevention funded more than 250 groups interested in organizing around prevention. Bass’ group was one. She opened shop in 1990 at 8500 Broadway in South-Central and began going door-to-door to find out how to improve the quality of life in a neighborhood where drugs, violence and poverty are endemic.

Today, she manages a staff of 14, some of the recovering drug addicts and alcoholics. She bristles at the low expectations outsiders have of blacks and Latinos, so she sets her standards high. She insists that staffers adhere to a dress code--jeans are taboo in the office--and show up for meetings on time. There’s a weekly agenda, and everyone, even the shy high school students who try to avoid it, must report on their projects. Staffers are encouraged to travel and see how other cities handle their prevention programs. It’s hard to pick out the few on her staff who hold college degrees because everyone is articulate and prepared as they talk on everything from alcohol-prevention programs to neighborhood canvassing to assess the needs of residents in the wake of the Northridge quake.

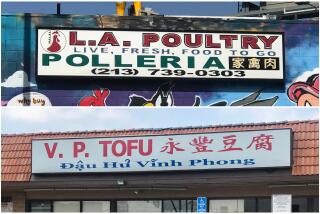

Earthquake or no, the needs are immense. When the coalition opened its doors in 1990, Bass was surprised to find the neighborhood nearly abandoned. In the early ‘60s, the merchants had been Jewish; now they were Korean with English a poor second language. The neighborhood then had been entirely black; now nearly half the residents were Latino, with as slim a grasp of English as the Koreans. And poverty and drugs threaten to waste whole sections of the remaining African-American community.

When Bass’ Latina assistant director, Sylvia Castillo, did Spanish-English translation at neighborhood meetings where they discussed the coalition’s program, she says, some of the cultural tension dissipated. But words went only so far in improving their lives. After the meetings, residents returned home down the same seedy commercial strips where illegal sales outnumbered legal ones, the squalid sidewalks lined with sofas and crates, where out-of-work men and women drank away their afternoons.

A year before the riots, Bass, Castillo and a group of residents began appealing to the Planning Commission and the Zoning Administration to rein in the problem liquor stores. Some 760 shops sold beer and wine in the neighborhood--which Bass defines as the area bounded by Alameda Street, Imperial Highway, the Santa Monica Freeway and La Cienega Boulevard. More liquor stores than in the state of Rhode Island. With the coalition’s help, residents identified 15 stores they wanted closed because the businesses and the sidewalks in front of them had long histories of attracting trouble. Castillo warned Bass that, because most of the owners were Asian, they’d be accused of race-baiting. “Don’t let them do that to us,” Bass replied. “That’s not the issue.” She then enlisted Kim’s help. Less than 24 hours after Bass met with Mayor Tom Bradley’s office, she watched on television as half the stores on her list, and more than 200 others, burned to the ground. “We stayed closed for four days,” she recalls. “Then we opened up and went to work.”

In her current campaign against the liquor stores, Bass has enlisted everyone from former Central American rebels to African-American retirees. Her special genius has been to appeal to the solid, hard-working blacks and Latinos who live in the neat blocks between the commercial strips, most of whom bought their houses before crack obliterated the neighborhood. They include people like Elizabeth McClellan, who moved to South-Central from Compton after a divorce in 1974 because it was the only place she could afford to buy a home. There, McClellan earned a teaching certificate and raised her last child. “This may not look like much,” she says of her immaculate one-story home, “but it was my independence.”

For two years, a crack house--”so busy it was like living next to McDonald’s”--had operated across the street. With the help of the police, the landowner and her neighbors, McClellan finally got the dealers to move on. Now she is one of Karen Bass’ foot soldiers, keeping journals on the troublesome liquor stores. Day after day, she and others monitor the storefronts, jotting down the presence of the illegal sofas and chairs that turn the pavement in front of the stores into sidewalk lounges. In the past two years, thanks to their efforts, 17 stores have been put on notice that their permits to operate are in question; another 20 stores destroyed in the fires have reopened, but with new restrictions, including security guards and restricted hours for some. Only one store of the original 15 has lost its license, a fact that disappoints but does not demoralize Bass.

For Bass, the liquor stores aren’t a black issue or a Korean issue; least of all are they a black versus Korean issue. The neighborhood simply has too many places selling alcohol and too many merchants selling it to drunks and underage customers. Those that are there, she says, should operate so that men, women and children can walk by or go in to buy milk without being harassed by drinkers. Entrepreneurs who come into the neighborhood, she adds, should be encouraged to try to sell something other than liquor. Maybe a decent hamburger, McClellan suggests. Never once does Bass refer to the “Korean liquor-store owners,” as a problem; she talks about the “owners,” those who maintain their stores and those who don’t.

At a recent hearing in front of the city zoning administrator, coalition members and residents go to great pains to reassure the owner of a liquor store that they do not want to see him shut down. “I’m not here to see their liquor license pulled,” says Alice Henderson, who lives at 90th and Flower streets. “The biggest problem that we have is respect.” George Hinton, active with the Fellowship Christian Community Church across the street from the liquor store, tells the hearing officer that he’s noticed an improvement in recent months but that the rules governing the liquor stores’ operations need to be written down. No one talks race, just specific problems.

“She’s done an incredible job,” says Hicks. His Southern Christian Leadership Conference of Los Angeles recently honored Bass with the Rosa Parks Award for outstanding community activist. “The whole liquor-store issue is ethnically polarizing, but she doesn’t polarize it. She’s never engaged in Korean bashing.” Bass, for her part, fumes that some television reporters are disappointed when they’re directed to Castillo for interviews. “They want to have my black face next to a Korean,” she says. “That’s not the issue.”

That’s why it was so important when Kim stepped forward to take her side on the liquor-store issue. His help has been “absolutely essential in blurring racial lines,” says Bass. “There are some Korean leaders who understand what we are trying to do, but they won’t go on record saying that we have a case. When Kim told the press how he felt, it helped immeasurably.”

That first breakfast at Roscoe’s did not end with Kim and Bass deciding they were multicultural soul mates. Kim was open to listening to Bass, but he also wanted to recruit her to become part of the Black-Korean Alliance, created by the county Human Relations Commission in 1986 after four Korean-American merchants were killed. Bass objected. “It was set up as merchant to resident--that’s an unequal relationship,” Bass says. “I also questioned why it was black and Korean when the neighborhood was heavily Latino. The black-Korean stereotype was already overdone.” Nevertheless, Bass agreed to attend some meetings. And Kim persisted. He learned about a grant from the city to work with teen-agers and suggested that they apply together. She agreed and increasingly found Kim responsive and helpful when she would call with a problem or an idea regarding the liquor store issue.

AT FIRST GLANCE, KIM WOULD SEEM AN UNLIKELY CANDIDATE FOR THE role of “translator” for about 200,000 Korean Americans in the Los Angeles area. In the 1970s, while Bass was finding her place in the civil-rights movement, Kim was at home mainly on the basketball court of his Bergen County, N.J., high school. His father, a chemist who sent for his wife and children when Kim was 3 years old, fretted that Kim would never amount to more than a jock. But when Kim attended Boston College, he began to confront the holes in his assimilation. Without the safety of close friends, he found it more difficult to ignore social slights or ethnic slurs. He turned to philosophy tracts to find some answers. “I was trying to get a better sense of where I was in relation to society, and a lot of it had to do with cultural identity,” he says. “I went through a whitewash period, thinking I was white, then realizing that wasn’t what I was,” he says. “I sort of broke down.” The crisis led him to take a year off from school to visit relatives in South Korea.

There, Kim says, “I found a lot of richness, a nation of people who looked and talked like my parents. But I thought my identity would be out there, and it wasn’t.” After graduating, Kim headed West, trying to get closer to the Korean-American community and himself. For five years, he ran the Korean Community Center in the East Bay. In 1988, he arrived in Los Angeles to take charge of the Korean Youth and Community Center, which runs everything from after-school programs to conflict-resolution counseling.

In six years, Kim has built the agency, which had an operating budget of $300,000 a year in 1988, into a powerhouse with an annual budget of $2.2 million, 70% of it from government funding. Today he manages a staff of 65. They are the children of privilege--young, college-educated, from comfortable families, with political views ranging from Christian right to liberal left. Like Kim, most speak at least some Korean and maintain close ties with the culture and their families. Kim, 36 and unmarried, explains that, as an only son, he has a duty to his parents to marry a Korean woman.

Tradition also meant that Kim, a member of the so-called 1.5 generation that came to the United States as children, could not easily challenge the authority of the first-generation Koreans. Kim waited from the sidelines, trying to encourage participation in multicultural initiatives like the Black-Korean Alliance, but he never got very far. Then, in 1991, Soon Ja Du, who helped run a liquor store on South Figueroa Street, shot and killed 15-year-old Latasha Harlins because, Du said, the girl was stealing orange juice. Du received a $500 fine and five years’ probation. “There were a lot of hard feelings on both sides, and there wasn’t any leadership from politicians,” says Kim. “After Latasha, it got progressively worse.” After the first verdicts in the Rodney King beating, it exploded.

The riots thrust younger Korean Americans like Kim into the spotlight. In May, 1992, few first-generation Koreans knew how to get their side of the story to the media. Kim and others, like Marcia Choo, program director of the Asian Pacific American Dispute Resolution Center, filled the vacuum. “First-generation Koreans had to acknowledge that we played a role,” Kim says.

Two years later, Kim is still struggling to hold onto that role--as evidenced at a recent meeting of the Korean American Inter-Agency Council, an umbrella organization of eight groups planning a national networking conference on Korean-American community issues. The participants, a mix of 1.5 and first-generation Korean Americans, start in English to discuss the choice of a keynote speaker for the conference. The elders name several prominent Koreans; Kim nominates Joe Hicks of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Everyone smiles. Then the first-generation representative launches into a long argument in Korean. In the end, Hicks is named as an alternate and Laura Jeon, director of the Korean Health Education Information & Referral Center, is the representative.

The second dispute is triggered over the use of a $30,000 grant. Speaking English, a program director from Kim’s agency says they need to hire someone to help with earthquake relief. In Korean, the first-generation representative replies that the Korean Youth and Community Center is getting too large, and the smaller, older organizations should get the money. The matter is tabled.

“It’s the classic split between the first and 1.5 generation,” Kim says later, explaining that the first generation wants the money to stay completely within the Korean community rather than move to more mainstream organizations. “The first generation is in survival mode. What they’ve done is admirable, but they’ve got to learn how to leverage with the mainstream.” Kim, who talks about someday running for office, partly on the strength of the alliances he’s formed with Bass and other black and Latino leaders, adds: “The African-American community has learned that well.”

The suggestion that there’s something to learn from African Americans isn’t likely to go down well in Koreatown. Many Korean Americans don’t define themselves as part of a rainbow coalition. “Coalition building is not embraced in the Korean community, as in others that have a long history of struggle,” says Marcia Choo. “Koreans think that if they work hard and stay out of trouble, they’ll be fine. They don’t put themselves in the context of Los Angeles. That’s why some of them say Bong Hwan isn’t being Korean enough.”

INITIALLY, KIM AND BASS WERE CONVINCED THAT, ONCE THEY STARTED talking, the hard part would be over. They believed it wouldn’t be difficult to find other profitable--and legal--business opportunities for the merchants whose liquor stores had burned to the ground. They were mistaken.

Of the two liquor-store owners who have surrendered their licenses, one has opened a coin laundry at Figueroa and 52nd streets; the other, David Whang, plans to open a laundry soon at 89th and San Pedro streets. Because Whang repeatedly assured local residents that his laundry would have an attendant to prevent the store from becoming a gathering place for troublemakers, they supported his request for a waiver of sewage-hookup fees. But when Whang submitted his plans, there was no mention of an attendant. The residents hauled Whang back into hearings and kept him there until the attendant was written into the plans. “The back and forth didn’t help relations much,” says Castillo.

The city hasn’t helped much, either, according to Patrice Wong, general manager for the Alliance for Neighborhood Economic Development. “We can’t replace 200 liquor stores with 200 laundromats,” she notes, but the city hasn’t any better ideas. The mayor’s office has stonewalled them, says Wong: “We take out our appointment books when we meet and say that we should talk about it, and they say, ‘We’ll give you a call.’ ” Kwoh of the Asian Pacific Legal Center agrees there’s been little city leadership to help ease racial tensions. “There are a lot of comments about support,” he says, “but it never goes anywhere.”

When Kim decided to back the conversion program, it was one of the few solutions he could see. “The only other position was for compensation, and I just didn’t see it happening because the victims didn’t have any political capital,” he says. As time goes on, however, he’s increasingly pessimistic. “Progress is still slow, and I have an uneasy feeling that if we aren’t able to convert enough businesses, criticism will be justified. This is the only time that Asians and African Americans have come together on addressing the problem. If we fail, it won’t be for lack of us trying. We didn’t get the necessary support from the political institutions that we were hoping to have.”

For its part, the city cries poor. “I don’t know that the mayor’s office can wave a magic wand to make a really terrible situation turn out right for everyone,” says Steven MacDonald, the mayor’s director of business assistance. “We have extremely limited resources.” His office, he says, is focused on persuading existing businesses to remain in the city. Creating new businesses or helping a community come up with a business plan, he adds, is beyond his office’s abilities.

In the meantime, the damage mounts in Bass’ neighborhood. The vacant lots left by the riots are now overgrown with weeds and scrub grass, but, as Bass drives through, she points out the hamburger stands that deal in drugs, the hotels where only prostitutes take rooms, the burnt-out men slouched against burnt-out buildings. “Nothing will really change until the economy changes,” she says.

Some of the liquor stores now have concrete blocks in place of the glass storefronts that shattered in the riots. The glass allowed patrol officers or neighbors to make quick security checks, but the owners argue that the blocks protect them from gunshots. Inside, they’ve raised thick plexiglass walls as further protection, adding another barrier to the cultural and linguistic walls that already existed. When a Latino customer shouts through the plexiglass to the uncomprehending Korean owner, asking the price of a bottle of Coke, the tension is almost palpable--and with reason; two Korean-American merchants were killed in South-Central in one four-month period last year.

Even so, the merchants seem determined to stay. Witness the recent sale of Century Liquor Store on South Figueroa, allegedly the scene of drug deals and frequent assaults, according to Bass. Last fall, Bass thought she’d put Century out of business when she hauled its African-American license owner before the zoning administration for a revocation hearing. “We were just at the point of getting the license revoked when we hear it’s being purchased by a Korean family,” she laments. “If an African American can’t control the situation, how can a Korean?”

Bass called Kim. But even if he could have stopped the license sale, it’s not clear that he would push the issue very hard. “You have to understand that a store in South Los Angeles is all some people can do to get ahead,” he says. “They can’t go to the Valley because they can’t compete with the other liquor stores where the owners are white and speak English.”

Because the options are limited, Kim’s loyalties are divided. “Translators,” after all, interpret for their constituencies--they don’t tell them what to say. In the end, the Korean family was kept from Century Liquor store by another of South-Central’s recurring dramas: The store has since burned to the ground.

DESPITE A TRACK RECORD that, for every step or two forward, seems to take one or two steps back, Bass vows her campaign will continue, spearheaded by a subsidiary group, Neighborhoods Fighting Back, which will also focus on the area’s motels, where prostitution and drug dealing are rampant.

Recently, her hopes were lifted when the 2nd District Court of Appeal upheld the city’s right to impose restrictions on liquor stores built after the riots. That helped soothe an earlier disappointment she faced when she and Castillo met with the new Riordan-appointed Planning Commission, a successor to the board that the community had painstakingly educated about the neighborhood’s objections to the liquor stores. The women say the new members--two Asians, one Latino and two whites--treated them to a condescending lecture on race baiting. (The commission now has one Asian, three whites and one Latino.) Instead of exploding, Castillo reports, Bass said they needed to talk. “She wanted to start again,” says Castillo. “That’s patience.”

It appears to have paid off. Marna Schnabel, president of the commission, says the commissioners educated themselves during the last several months. “Once done, the coalition and the commission understand one another,” she says. “I believe what the coalition is doing is very positive. They do a lot of very effective work in the community. Some of us weren’t aware of their history.”

Starting again, and again, and again, may be the only way to address the racial and ethnic divisiveness that shapes South-Central. Perhaps recognizing that their best hope lies with the next generation, Bass and Kim recently started a graffiti-removal business for Latino, Korean-American and African-American teen-agers. They’re sufficiently encouraged by the results to consider more multicultural partnerships--as long, Bass stipulates, as the participants are also learning a skill, like entrepreneurship or leadership.

They are learning less tangible skills, too. When the graffiti-removal team--now composed of 15 Koreans, 10 Latinos and 10 African Americans--was first organized, their training included some consciousness-raising: “We got into different groups and discussed stereotypes, like how Koreans are supposed to always eat garlic, and all black people are on welfare or do drugs, all Latinos sell oranges by the freeways, stuff like that,” says Elmer Roldan, 15. “People don’t really know what they are talking about. They make it up because of ignorance.”

Training teen-agers like Roldan and his teammates is just another way of translating suspicion and ignorance into empathy. “Slowly,” Bass says, “they have become friends.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.