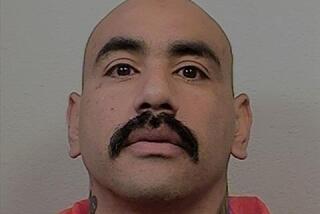

A Close-Up Look At People Who Matter : Former Gang Leader Reaches Out to Youths

Running rapid-fire through the facts and philosophy of his life, Miguel Rios talks about his days as a gang leader in South-Central Los Angeles, his two dead brothers, the times he’s been shot and how he draws on these experiences to reach teen-agers today.

“You have to be real with these kids,” said Rios, 35, head of United Parent Services of America, a small all-volunteer group he began three years ago in his Palmdale home.

The group opened an office on Palmdale Boulevard six months ago with 10 volunteers. Without enough funding to light more than half the office, they talk with optimism about opening their first branch office to serve the Native American community in Gallup, N.M., within three months.

On their hot line, Rios and his group handle calls about drugs, runaways, conflicts with parents and pregnant teen-agers. He spoke about a recent call from a parent whose daughter was acting strangely. The daughter was reacting to PCP.

Rios said he went to the home, had the girl drink milk and then walked her around to help her come down from the drug. He told the family they should try drug counseling.

Rios, who works as a school security officer and as a checker at Ralphs in Encino, said summertime in Palmdale is the worst for youth because they have little to do. “Some of it we’re still dealing with,” he said.

As a security officer at Highland High School, Rios has met many of the youths he has later helped. “He’ll give you advice,” said Tracey Maestro, 17, a student.

“I look at him as a big brother,” said Monique Ramirez, 16, who was with Tracey and other teen-agers at the organization’s office, planning a carwash.

“I don’t have any brothers anymore,” said Rios, who lost his two brothers to gang-related violence. “These kids are like my little brothers.”

One of his best friends, Frank Murillo, had once been one of his bitter enemies. Rios and Murillo met formally for the first time at a district meeting for security officers just after Rios began his group. They looked familiar to each other, but only after talking for several minutes did they realize they used to be members of rival gangs.

“My goal is to see kids go to college,” said Murillo, who now volunteers with Rios’ group. An education can get you anywhere you want to go, he is fond of saying, but a gang can only lead you to prison.

“The message has to be made that kids can change,” said Rios, who remembers the words of a police officer at the scene of a shooting when he was a teen-ager: “One dead. One in jail. That’s two down.”

The words were devastating to Rios, who felt the world cared little about what happened to him.

But a teacher at Los Angeles High School gave Rios a chance to succeed. When that teacher later became a principal, he offered Rios a job. The catch was that Rios had to agree to finish school.

Most of Rios’ friends did not finish school. Several ended up in jail. “I should never have made it,” said Rios, who displays his diploma on his wall.

Too often, he said, society has branded teen-agers as not worth saving. “One girl said to me, ‘The only time I get attention is when I get in trouble,’ ” Rios said.

He identifies with the teen-agers’ anger and frustration. One answer, he has found, is to teach them about their culture and identity to help them learn how to live and to have pride.

Last year, Rios, who goes to great lengths to make contact with teen-agers he wants to help, went to a white supremacist club meeting to talk to youths.

A few of those youths later showed up at the office of United Parent Services of America and volunteered their time. In that office, no one talks about their previous gang affiliations or beliefs. All of that is left behind.

“One of the thrills I get is when kids tell me, ‘I want to be like you,’ ” Rios said. “That floors me.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.