AGAINST A WALL : African American Artists Continue the Quest to Be Shown and Supported by the Mainstream

Black almond-shaped abysses and thick kissy-lips characterize the oft humorous African masks with ghettoish attitudes that hang in one room of the gallery on Main Street in Santa Monica. Another room exhibits Afrocentricism in the abstract, as fierce, Motherwellian strokes dominate black-on-white shaped canvases splashed with fiery red and gold. In yet another room, the theme is distinctly female Afroerotic symbolism, as white snakes violate giant blood-red buds.

I’m wafting through the white rooms of M. Hanks Gallery. In my fantasy life, I spend all my cocktail hours attending gallery openings, but I’ve been so busy that I’ve not only missed several other exhibits but I’ve also let my museum membership lapse. Worse, I’ve missed the latest, hippest, elitist controversy shaking the already tremulous world of African Americans--a show called “Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art.”

Determined to get the PC skinny, I hook up with Eric Hanks, whose gallery is one of the few in Southern California to feature black artists in, but mainly outside, the mainstream. When I tell the 41-year-old photographer from Washington, D.C., that I’m here for feedback from the front line, he laughs. “Essentially, black art in America has always been controversial and, for the foreseeable future, will be,” he says. “I understand where the people who didn’t like the Whitney Museum show were coming from. Historically, we’ve been subjected to ridicule and vilification of our character.”

When I suggest that another good idea was again derailed by instant experts, he empathizes. “They’re hypersensitive about how black people are portrayed. I saw the show. There was some very interesting work, some very strong and some not-so-right,” he says, shrugging. “Controversy may place an unfair burden on curators, but they should be aware that they’re going to be under intense scrutiny.”

But, I remind him, local black artists weren’t consulted or invited to participate. Hanks agrees but adds: “There’s residual racism felt deep down inside black people. It’s still too close to home. Many prefer traditional African art, especially whites. If you feel, in your heart, that blacks can create good art, it’s a subconscious way of saying blacks are equal to you. My message to all people: Give African American art a fair chance. But on the whole, whites will not buy into the black community.”

Unfortunately, most blacks can’t afford to support black artists and prefer the conceptual to the abstract. Hanks, like me, is an exception who proves the rule. “Our family collected art,” he says. Like him, I grew up hearing complaints about the lack of mainstream support for blacks in the arts. “Museum shows were rare for black artists who wanted the chance to see their work shown respect,” he says. “The broader public needs to know that great black art is no mutation that’s created by a handful.”

I remind Hanks that I attended the opening of his exhibit of three artists, all black males, during the curfew following the ’92 riots and note that he was ahead of his time. There were no reviews. What keeps him going, he says, is “luck and a positive self-image.” He’s shown works by artists who are becoming increasingly more prominent in the larger art world: Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Jerome B. Meadows, Michelle Talibali, Elizabeth Catlett. “Things have improved somewhat, despite controversy,” he says.

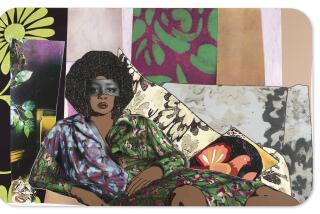

Our conversation over, I hate to leave with empty hands. I settle on a Talibali poster, and Hanks rings up the sale. I ask for his list of exciting emerging artists. “Watch for William Pajaud, John Offutt, Monica Brown, Gene Cooke and--oh, wait a minute, let me show you this--Phoebe Beasley.” He rushes to a back room and brings out the mock-up of a poster for Beasley’s upcoming L.A. show. “Beasley and Pajaud aren’t exactly new artists,” Hanks admits. “By emerging , I don’t necessarily mean a young artist. All black artists are emerging,” he says with a smile, “in a sense.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.