Bacterium’s Immunity to Powerful Drug Bodes Ill

Since it was launched in 1958, the antibiotic vancomycin has been considered the big gun against troublesome bacteria that ran roughshod over less potent antibiotics. Its manufacturer, Eli Lilly & Co., proudly touted it as “a drug before its time.”

When doctors treating very ill patients wanted the ultimate protection against a wide range of bugs that could cause fatal infections, they would turn to vancomycin.

What no one expected in 1958, or even as recently as a few years ago, was that a bacterium would outsmart every antimicrobial, including mighty vancomycin, the so-called drug of last resort.

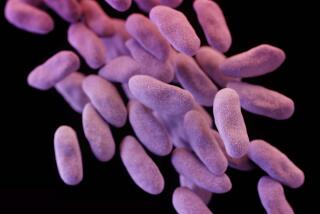

Such a bug has emerged, and it is producing plenty of anxiety in hospitals and acute-care nursing homes across the country. The organism is a gastrointestinal bacterium called enterococcus that was considered harmless until it began to mutate out of the reach of every drug, lastly vancomycin. First reported in Europe in 1988, vancomycin-resistant enterococcus has spread methodically westward; sporadic cases began cropping up in California in 1994.

And while vancomycin-resistant enterococcus is no Andromeda strain, its presence signals the ominous dawn of an era in which infectious diseases that once were put down easily with antibiotics could become incurable.

Outbreaks in Africa of the deadly Ebola virus have helped awaken the public to the threat of incurable infectious disease. But experts say that what the American public, and even their physicians, may fail to realize is that the problem is now at hand as common bacteria find ways to survive an arsenal of overworked and misused antibiotics.

“The general public is at greater risk of antibiotic-resistant organisms than some exotic thing like viral hemorrhagic fever,” says Dr. Hildy Meyers, an Orange County Health Department epidemiologist. “Vancomycin is a last line of defense against some infections.”

And that line is wavering. About 14% of all hospital-acquired enterococcal infections are now resistant to vancomycin, a twentyfold increase from 1989, according to a federal study of intensive care units.

Reducing the risk of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus, known as VRE, has become a priority at acute-care hospitals and nursing homes, where the bug can thrive because of a combination of circumstances: very sick patients, excessive use of top-flight antibiotics and highly infectious environments.

Three small outbreaks have been reported in Los Angeles-area health facilities since 1994, and sporadic cases have cropped up in Orange County. Nationally, every state has reported VRE, but the majority of outbreaks have been concentrated in the Northeast. Several facilities, including a hospital in New York state and an acute care nursing home in Santa Clara County in Northern California, acknowledge battling VRE outbreaks involving dozens of patients.

But public health officials say most hospital administrators are so sensitive to the fact that their facilities may be harboring an incurable organism that they are reluctant to acknowledge VRE cases.

For this reason, VRE and the threat that even more dangerous bacteria could become resistant to vancomycin have largely escaped notice--until recently.

Awareness increased last month, when the Journal of the American Medical Assn. dedicated an entire issue to emerging infectious diseases and antibiotic resistance.

“We need to call attention to the crisis we’re in,” says Dr. Donald A. Goldmann, an infectious diseases specialist in Boston who warned of the problem in the journal.

In California, health officials have had the dubious advantage of knowing that VRE was heading their way. “VRE has moved consistently westward,” says Dr. John Rosenberg, an epidemiologist with the state Department of Health Services. He is attempting to track the increase in cases, improve laboratory testing methods and educate health officials. “We’re doing much more [to prevent] it than any other state that I’m aware of. But whether it does any good, I don’t know.”

There is a reason for Rosenberg’s pessimism: Enterococcus isn’t easy to stop.

The organism lives silently in the intestinal tracts of most people, where it causes no illness. In some cases, it breaks into the bloodstream and becomes an infection. Even then, most healthy people with good immune systems fight it off.

Enterococcus becomes a problem when bloodstream infections occur in very sick individuals or those recovering from major surgery, whose immune systems already are overwhelmed. In these cases, an antibiotic is needed or the infection can greatly reduce the chances that the already-weakened patient will recover.

The crisis occurs when the patient--who already may harbor harmless enterococci--has acquired a strain that is vancomycin-resistant.

Such transmission can occur through hand-to-hand contact, usually from microscopic fecal matter. But it often spreads because of its ability to live for days on surfaces such as counter tops, says Dr. William Jarvis, an infectious disease specialist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

Moreover, an infection can remain active--and contagious--in a patient for weeks or months.

“It’s a sneaky organism,” Jarvis said recently at a symposium for health care professionals held at the acute-care facility THC-Orange County. “By the time you identify your first patient with infection, usually 10 times more patients are already colonized.”

Studies show that those most likely to develop VRE bloodstream infections are extremely sick, have taken vancomycin previously and have been hospitalized before. Such conditions make the bug a hazard in cardiac care, pediatric and adult oncology, renal and intensive care units. Acute care nursing homes, which often have looser infection control practices, are cited as potential reservoirs for infection.

In L.A. County, health officials have investigated two outbreaks, both in hospitals associated with nearby skilled nursing facilities. The county is gathering information on a third at an acute care facility.

There is little that can be done for someone with VRE other than to continue to fight whatever else ails the patient, Jarvis says.

“You name the combination [of medicines], they’ve been tried and have not had any effect at all,” he says. “And I don’t know of any agent that looks very promising on the horizon.”

One antibiotic has shown promise in treating VRE, but the drug still is being investigated.

It is difficult to assess how damaging the spread of VRE is to patients, because the very sick people who usually contract it are already at high risk of dying from their underlying diseases, experts say.

In the first reported outbreak in Los Angeles, which occurred in February 1994, 31 people were identified as having the bug. Within six months, half were dead, says Dr. David Dassey, an infectious disease expert with the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services.

“It’s hard to calculate an attributable mortality rate [for VRE],” he adds. “Did they die from it or with it?”

Officials of the Centers for Disease Control agree that it is difficult to tell if VRE increases the chances of dying, although one study indicated that there was no significant increase. But such infections still exact a toll, Rosenberg says.

“The efforts to treat these infections are going to be costly and will end up prolonging the patient’s stay in the hospital,” he says. “And there is the belief that some patients will die who would have lived otherwise.”

Still, VRE is not so much a problem for what it is as for what it represents. If enterococci could become resistant to every antibiotic, so too could other--more dangerous--bacteria.

“If there is anything good to say about VRE, it’s that enterococcus is a very boring organism,” Dassey says. “It doesn’t do a lot. When you compare it to strep and staph, enterococcus has no dangerous enzymes or toxins like staph and strep.”

Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria both produce enzymes that break down tissues, invade areas where they don’t belong and release deadly toxins. If not treated swiftly and with the right antibiotic, staph and strep are deadly. Increasingly, officials are seeing strains of staph and strep that are resistant to several antibiotics.

Strains of Staphylococcus aureus have been identified that are resistant to everything but vancomycin, Goldmann says, as are a small number of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates.

Scientists have long understood that bacteria have efficient mechanisms for acquiring dangerous new genetic traits to elude antibiotics. The resistant gene in one kind of bacterium can be transferred to a different type or species of bacterium.

“The underlying problem--which everyone is awaiting and fearing--is the communication of the vancomycin-resistant gene from the enterococcus organism to the staphylococcus,” Dassey says. “Then we will have a germ resistant to everything, a bug which also has these enzymes and toxins.

Experts say this potentially devastating scenario is reason enough to try to stop VRE in its tracks.

For the past year, Jarvis, Rosenberg and Dassey have been working their respective territories, encouraging medical societies, physicians groups and hospital administrators to change the way they do business when it comes to infectious disease.

They are focusing on two problems that seem to have precipitated the emergence of VRE: over-prescribing antibiotics and lax infection control procedures in acute care health facilities.

Antibiotics came into widespread use in the early 1940s with the advent of penicillin. The new medications quickly curtailed deaths from such ailments as pneumonia and strep throat. Pharmacy shelves were so brimming with powerful antimicrobials that by the 1980s, drug manufacturers began to scale back or end their efforts to design new antibiotics.

One by one, however, bacteria found ways to outsmart the drugs. As the list of ineffective drugs grew, physicians turned to the few remaining broad-spectrum antibiotics that offered good protection but were so expensive or difficult to administer that they tended to be used as a last resort, like vancomycin.

Eventually, experts say, that practice led to an overuse of vancomycin, which is a problem of huge proportions.

In investigating the first VRE outbreak in Los Angeles County, “the most common antibiotic used at that hospital, which also supplied the nursing home, was vancomycin,” says Dassey, who dashed off a letter to the hospital’s infection control committee imploring it to review its use of the drug.

“That is where the crunch will be, with the judicious use of antibiotics,” Rosenberg says. “Hospitals can set up rules for what doctors can prescribe. They might not be happy, but [hospitals] have the power to do that. You have no power to do that outside the hospital.”

The public, too, will play an important role in efforts to reign in antibiotic use. Misusing medications, such as taking seven days of a 10-day dose, kills off the weakest bacteria but allows the hardiest to live on in the body’s competitive environment.

Moreover, people often want their doctors to prescribe antibiotics for viral infections, which is useless and helps promote resistance.

“It’s important for the general public to understand that if they go to the doctor with a complaint and the doctor doesn’t give them an antibiotic, that doesn’t make that person a bad doctor,” Meyers says.

East Coast hospital administrators battling some of the largest VRE outbreaks (one instance included 214 patients) have had to fight their staff doctors to discourage the use of vancomycin, Jarvis says. (“The organ transplant doctors were all saying, ‘Get ready for all of our patients to die,’ ” Jarvis says of one Baltimore hospital’s particularly vitriolic staff arguments about curtailing vancomycin. “They didn’t die, by the way.”)

It has been easier to convince health professionals that infection control--hand-washing; wearing masks, gowns and gloves; thorough room cleaning--has to improve.

“Infection control programs in most hospitals are really quite good,” Goldmann says. “Where the process breaks down is in the care of individual patients where people are very sick and [staff] are overworked.”

When budgets are tight, janitorial services--which are crucial in helping control the spread of infection--are often the first to be cut back, Jarvis adds.

“Infection control is a non-revenue-generating part of the hospital,” he says, adding that one hospital’s decision to reduce its janitorial services may have played a role in its VRE outbreak.

No hospital competing for patients wants to be viewed as crawling with germs, so many facilities keep their VRE outbreaks quiet. VRE does not have to be reported to health departments, although county and state officials have asked for voluntary reporting.

And like virtually all health officials involved in monitoring VRE, Dassey is reluctant to disclose the names of the local facilities with outbreaks because the publicity might lead to “an unfair public perception.”

“The problems that induce the development of VRE are everywhere,” he says, noting that it is misleading to single out a facility with an outbreak when many other institutions also may have problems with antibiotic overuse and infection control.

Still, there are dangers in keeping a lid on VRE outbreaks.

Goldmann is particularly alarmed by what he says is the occasional practice of sending patients with VRE to a nursing home or another hospital without telling the receiving facility that the patient has VRE. The discharging hospital is usually afraid that the receiving hospital will not accept the patient.

Secrecy, clearly, has no place in an emerging public health threat. The recent report on infectious disease contained terse instructions on what pathologists should do if they turn up a strain of vancomycin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae: Verify it, save the isolate and report it.

And the threat of a Staphylococcus aureus microbe resistant to vancomycin has loomed so large that a CDC task force is developing contingency plans for handling an outbreak, Jarvis says.

“That’s going to be a real public health emergency when that arrives,” Jarvis says. “You’re going to need a SWAT team to stop it.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

How Bacteria Resist Antibiotics

Resistance centers around a loop of DNA called a plasmid.

HOW ANTIBIOTICS WORK

Antibiotics are designed to penetrate the cell wall of a bacterium and destroy its protein.

* Dissolve cell wall

* DNA loop (plasmid)

* Stop protein production

* Block instructions for protein synthesis

****

MUTATIONS

A bacterium can develop a genetic mutation, however, to protect its protein or even strengthen its cell wall to keep the antibiotic out. This bacterium replicates and is now carrying a gene that is resistant to the particular antibiotic.

Resistant gene (plasmid)

Ordinary cell

Resistant cell

****

SPREADING RESISTANCE

1) Compounding the danger, the bacterium can share its resistant gene with other, more harmful, bacteria. It does this by first attaching itself to another bacterium.

2) The resistant bacterium then makes a copy of part of its DNA, called a plasmid, that carries the resistant gene.

3) The resistant gene is transferred to the attached bacterium.

4) The second bacterium is now capable of surviving the antibiotic’s attack.

Sources: Newsweek, Los Angeles Times