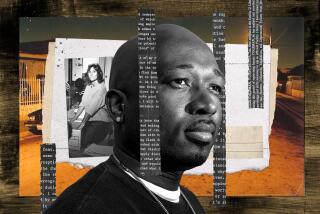

Life After Homicide : Veteran Santa Ana Detective ‘Buck’ Buckels Retires From Killing Field

SANTA ANA — In Ferrell Buckels’ 21-year parade of the dead, the ice cream man with a bullet in his chest was first in line.

Buckels was new to the Santa Ana Police homicide unit when he crouched over the hapless robbery victim in the back of his ice cream truck on a summer day in 1975. It would take Buckels seven years to cuff the killer on his first murder case, making it one of his toughest.

“Sometimes they take awhile,” Buckels recalled. “That’s just how it is. That one, though, seems like a million years ago.”

After more than two decades of back-alley stabbings, bedroom poisonings and storefront shootouts, Buckels has called it quits. No more midnight call-outs or morgue visits for badge No. 113, no more cat-and-mouse games in the interrogation room or trips to the witness stand.

The 56-year-old detective retired last week after, by his estimation, about 350 homicide investigations and, before that, seven years as a patrol cop and working the vice squad. Around the station house, he is regarded as a walking encyclopedia of murder and mayhem, a professor of killings.

“There is a void in the law enforcement community with his departure, no doubt about it,” said Santa Ana Police Capt. Dan McCoy. “Buck has been the dominant investigator in violent crime in this whole county, and that’s hard to lose. This is the passing of a legend. I mean that.”

One of Buckels’ old partners, Sgt. Irma Vasquez, called him “simply the best investigator, the guy you think of when you think of what it means to be a good cop,” while the department’s chief, Paul Walters, called the dean of detectives “one of a kind.”

None of this gushing sits well with Buckels. A quiet, lanky man with a rumbling voice, he has little tolerance for attention or fuss. With a pained look, he made it through the retirement luncheon and the office party with the chocolate cake and all the gifts and accolades.

Vasquez, Buckels’ partner for nine years, could read the look on his face. “If he had his way, he would have worked right up until quitting time on his last day, got up and walked left without a word. That’s Buck. He would have just walked out.”

He takes with him a huge chunk of department history. He worked, for instance, the 1985 bombing death of Alex M. Odeh, the regional director of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee. The slaying was a suspected act of political terrorism.

Buckels met with federal agents again earlier this year to discuss the still-unsolved case, sharing the information he has stashed away over the years. “That was a big one,” he says.

He also handled the offbeat, such as the case of the flamboyant Rollen Fredrick Stewart, a.k.a. the Rainbow Man, who was convicted of planting stink bombs and, in 1992, of taking hostages at a Los Angeles hotel. There was no murder, but Buckels helped anyway.

And Buckels’ last case? The recent shooting of a good Samaritan who was gunned down while trying to foil a purse snatching on the way home from Sunday church services.

Buckles’ career began with an ice cream man who was killed in a robbery where the attacker got no money. It ended with a man chasing his own death and a purse with $30 in it.

“A lot of times these things are just senseless,” Buckels said.

The detective has the image among his peers as the department’s quiet, cool cowboy, the man who still carried a hulking .45-caliber long-barrel Colt revolver in an era of small, sleek semiautomatics. His colleagues chipped in to buy Buckels a collectible rifle as a farewell gift, the sort of gun you see tucked into saddle bags.

A little plastic prospector stood atop the white icing of Buckels’ going-away cake, a nod to his love for lonely expeditions through the rolling hills and washes in a mining area in Humboldt, about 16 miles outside Prescott, Ariz.

The veteran cop heads out there whenever he can, to dig for bottles and rusty old horseshoes and pick heads. When men still worked Humboldt’s gold mines, Buckels’ grandmother owned a general store there and his father would ride a burro past the mesquite and scrub on his way to school.

*

“I collect the old bottles I find there,” he says. “I like to stop and think about what the things have been through, about who has handled them in the past. I just like digging.”

The miner’s mind-set has served Buckels well. Vasquez and others describe his methodical, meticulous ways with awe. “He is relentless. He never gives up. No stone unturned.”

That approach doesn’t lend itself to drama. Buckels shrugs when asked about his most exciting cases or dangerous moments. His mining techniques are are more erosion than explosion. Long days and long nights wearing away at alibis and evidence.

Far more common than Odeh and other high-profile cases were the steady stream of so-called mundane murderers, the betraying spouses or two-bit stickup men. After years of hearing their stories, surely Buckels must have gleaned something about the human heart or the nature of evil.

But, if he has, he isn’t saying.

“Who knows why people do what they do? It’s different things, different people. I couldn’t say.”

Vasquez said her old partner’s greatest strength is his ability to gently wrangle the truth out of murder suspects, making them so comfortable that they open and share. McCoy describes the process as “taking a walk” with the suspect, providing killers with a chance to do what they want to do most: confess.

Buckels nods and smiles. Perhaps the most satisfying part of his job has been shepherding the guilty toward the truth and a jail cell.

*

“You lead up to it,” he said. “It’s like a game. They lie a little when they get nervous and then they lie some more. They start stumbling and lying until they’re blue in the face. They bury themselves.”

And then Buckels digs them out.

“It’s amazing,” Vasquez says. “They hear that deep voice of his and they just open up. They’ll tell him everything.”

When asked what the hardest part of his job has been, the veteran lawman’s eyes search his cup of coffee. He doesn’t have to think about the answer. “The kids,” he said.

Buckels said he is “lucky” to have handled only a handful of murdered youngsters in his lengthy homicide tenure. He has three kids of his own, all adults now.

“With some of the older people, especially the drug dealers and gangbangers, well it’s not so hard with them,” he said. “They made a choice a lot of the time. But the kids . . . it’s just not right.”

Another hard part is the open cases. The nagging, unsolved killings that have kept him awake at nights. Those were all passed on to all the younger detectives when Buckels walked out last week.

“The hardest thing to grasp is that you won’t solve them all,” he said. “That’s a tough pill to swallow. With homicides, you have this feeling that they all should be. But you have to accept the reality that some will not be solved. You just try your best and keep digging for the truth.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.