Death Penalty Still Stings the Mustangs

DALLAS — On Feb. 25, 1987, the NCAA handed out an unprecedented penalty, canceling the football program at Southern Methodist for 1987 and severely restricting it in 1988 for numerous rules violations. The school decided not to play in ’88 either, and the football team didn’t return to the field until 1989. Since then, the Mustangs have not had a winning season. In the 1990s, SMU has the third worst record out of 109 Division I-A teams. The following is a look at what’s happened at SMU over the past 10 years.

*

It was Nov. 11, 1989, and the Southern Methodist players were scared, almost terrified that the time had come to find out the real meaning of the NCAA’s “death penalty.”

There they were, a ragtag bunch of freshmen walk-ons preparing to play No. 1 Notre Dame at South Bend, Ind. The scrawny group was the best the Mustangs could muster in their first year back after the program was effectively suspended for two years by the NCAA in the toughest penalty it ever inflicted.

“The challenge,” recalled SMU coach Tom Rossley, who was Forrest Gregg’s assistant back then, “was to get them to come out of the dressing room.”

The Mustangs made it to the field, and Irish coach Lou Holtz had his team go easy on them. Notre Dame won by only 53 points, 59-6.

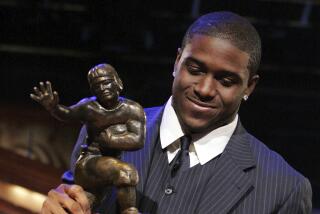

The loss was nothing like the 95-21 whipping inflicted by Houston several weeks earlier. Eventual Heisman Trophy winner Andre Ware threw six touchdown passes in the first half and his second-half replacement, David Klingler, had four. Gregg refused to shake Houston coach Jack Pardee’s hand after the game.

The Notre Dame game was the humbler. It demonstrated just how completely the death penalty had devastated a once-proud football program.

It also showed the depth from which SMU--a perennial Top 20 contender only a few years before--had to climb on its long road back.

And what a road it’s been. Four of seven seasons since the Mustangs’ return have included only one victory. Losing records in all seven years. An overall mark of 13-61-3.

Craig James, who teamed with Eric Dickerson in SMU’s “Pony Express” backfield that led the Mustangs into national title contention in the mid-1980s, remembers the good old days.

“I found myself, about two or three years ago, at an Alabama-Auburn game,” said James, now a television analyst. “The crowd was crazy, and I thought to myself, ‘Whoa, now this is college football.’ And I thought, ‘That’s what we used to be.”’

With SMU’s move from the disbanded Southwest Conference to the softer WAC, and its most experienced team to date, Rossley said a winning record may finally be within reach--nearly 10 years after the death penalty was imposed.

“This is the first time we’ve had a mature team,” Rossley said of a squad that includes 17 returning starters and about 30 fourth- and fifth-year players. “Hopefully we can keep them all healthy.”

THE AFTERMATH

On Feb. 25, 1987, the NCAA lowered the boom on Southern Methodist after finding that a banned booster paid 13 players thousands of dollars--even while the team was on probation for similar violations.

It was a serious case, one that entangled even former Texas Gov. Bill Clements. And it required serious action. But officials at the private Dallas university never expected the punishment that followed.

The NCAA infractions committee invoked a never-before-used provision in its repeat-violator legislation, banishing SMU football in 1987 and severely restricting it in 1988. SMU decided not to field a team again until September 1989.

Almost every player transferred. With no football, the social centerpiece at a school known for a preponderance of BMWs in the campus parking lots, homecoming was reduced to festivities planned around a soccer game.

It was up to Gregg, an SMU legend and NFL Hall of Famer, to put what few pieces remained back together.

The first team he assembled wasn’t pretty. There were more than 70 freshmen, many of whom were walk-ons recruited from the student body.

“It was a bleak outlook each week,” Rossley said. “We were just worried about how to score a touchdown . . . we’d figure out how to win later.”

Smaller and less experienced than their opponents, 13 Mustang players sustained knee injuries that required surgery in that first year back. Trainer Cash Birdwell said the average number is about three or four per season.

“There were some guys on the team that I questioned whether they even played high school football,” said Mitchell Glieber, a receiver and co-captain on the 1989 team. “There was not a lot of talent out there.”

Amazingly, the ’89 team won two games, including a 31-30 thriller over Division I-AA Connecticut in its second game. Overall, however, it was apparent the Mustangs were years away from a winning record.

THE LONG AND FRUSTRATING ROAD

Steve Wilensky, the executive director of SMU’s booster group, the Mustang Club, likens the NCAA’s use of the death penalty to the United States’ use of the A-bomb against Japan in World War II.

“We had no idea what the post-dropping devastation would be,” Wilensky said. “That’s pretty much what happened.”

Only a few years earlier, SMU and the “Pony Express” challenged for the national title.

“At that point, SMU was talked about as being the team of the ‘80s,” Wilensky said. “SMU in the early ‘80s is about like Nebraska is right now.”

But after the death penalty, SMU was left with only a handful of players and no recruiting base. The school also tightened admission standards in an attempt to return integrity to the program.

As a result, SMU players went through one frustrating loss after another, season-in and season-out. Only two other Division I-A schools, Kent and Ohio universities, have worse records in the ‘90s.

“I think it wears on them mentally during a four-year career,” said Birdwell, the team’s trainer for 24 years. “They had a lot of character when it came to sticking to it, and yet I know it had to be tough on them.”

Rossley, who left SMU for an assistant’s job with the Atlanta Falcons after the 1989 season, found out just how tough the task was when he returned as coach in 1991.

In five seasons since, the Mustangs’ best effort was 5-6 in 1992.

“I don’t think the NCAA realized how significant the blow was going to be,” James said.

Rossley and many others at the school thought last year would be a turning point. It wasn’t. Chris Bordano, the Mustangs’ best linebacker, was sidelined with a back injury. And then quarterback Ramon Flanigan went down with a dislocated hip on the first snap of the season.

FIRST AND LAST

SMU was the first school ever hit with the death penalty. NCAA officials won’t say so, but it’s also likely to be the last.

Since SMU was penalized, several programs have technically been eligible to receive similar punishment. None have.

There are at least two examples in Texas alone. Houston was eligible for the punishment in 1994 because of misconduct during the Jenkins era but drew minor sanctions.

At Texas A&M;, nine football players in 1994 took pay from a booster for work they didn’t perform. But instead of the death penalty, the Aggies got five years’ probation and were prohibited from TV and bowl games.

David Swank, an Oklahoma University law professor and chairman of the NCAA infractions committee, insists the death penalty remains in the committee’s arsenal.

“It would have to be a very severe case,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean it may not or will not be used in the future.”

Swank said committee members have considered assessing the death penalty in some cases, including Texas A&M;’s, but schools have managed to avoid it by dealing with problems quickly and honestly when they arise.

The SMU case might have something to do with that.

“I assume that’s part of the reason,” Swank said. “But also . . . schools have said, ‘It’s better to cooperate and get these matters behind us quickly.”’

As the SMU football program limps along, bitterness toward the NCAA is slowly fading.

There is the lingering perception, however, that the Mustangs were unfairly used as an example. Worse, school supporters say, that example amounted to nothing since the penalty has not been used again.

“The very sad thing is that had the death penalty been given to other schools, college football could have been cleaned up,” said Wilensky. “I would have been happy for SMU to have taken all the slings and arrows that we took had we been the school that started the cleanup of the NCAA, had they not backed off.”

Hope, meanwhile, springs eternal on the manicured campus known as “The Hilltop.”

Rossley isn’t promising a winning season in 1996 but said it’s possible. And he stresses that glory can be achieved with integrity this time.

Wilensky said that’s been the goal at SMU since ’87.

“It’s the belief that we’re on the threshold of achieving that in football,” he said. “We’re in the bud stage. We think this is the year that it flowers.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.