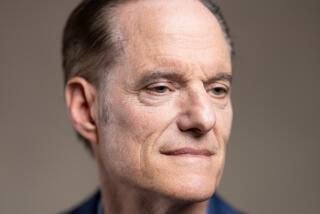

Idealism Pays for Founder of Youth Home

Ivelise Markowitz’s heart still stops at the memory, 28 years ago, when her 1960s idealism that launched a group home for troubled girls ran into the brick wall of reality.

Penny Lane was empty.

After going out on Christmas eve in 1969, Markowitz and her staff returned to the home in Altadena to discover that the 17 girls they cared for had run off.

The incident could have shut down the National Foundation for the Treatment of the Emotionally Handicapped, also called Penny Lane--from the Beatles tune--just two weeks after it had opened.

“We started with the idea that the kids are supposed to set up the rules, and that somehow this group was going to reach for higher goals of everybody helping everyone else,” said Markowitz, the founder and executive director. “It didn’t work.”

Over the next couple of days, the girls straggled back to the facility, then a beat-up, converted convalescent home that had been spruced up by bearded, long-haired friends and fellow dreamers.

“If anything had happened to them, I wouldn’t be sitting here today,” Markowitz said.

Structure and discipline, along with unconditional love, were added to the recipe to make Penny Lane work.

A few months later, the roof of the converted nursing home collapsed. The insurance money was enough to move the group to a larger, better-maintained facility in what is now North Hills. Today the agency cares for 86 girls--plus 18 boys in separate homes--and has 32 employees. Penny Lane also directs an agency for 325 foster children.

“I always wanted to work with bad kids,” Markowitz said with a smile natural to her dry wit and sense of humor that propels her through crises. “It’s the rebel in me.”

Markowitz was working for the Los Angeles County Probation Department in the 1960s when she realized that while there were plenty of facilities for troubled boys, there were few available for girls.

“They were sitting in juvenile hall waiting to be placed somewhere,” said Markowitz, who came to California from Puerto Rico in 1958 at age 17. She was in her early 20s when she set out to create an agency to meet that need, and ran into roadblocks.

“I didn’t see how she was going to pull it off,” said Bob Morris, a retired probation officer and former co-worker. “But I did have kind of a clue that she was going to succeed. She had an obsession with the idea.”

Her first attempt to get a state license failed. “Too young, too inexperienced,” she was told.

“She was a minority trying to get into an arena that only the establishment, old-line folks were involved in,” said Bob Crigler, another former probation department co-worker who later would be assistant director at Penny Lane for nine years. “To survive, she had to be clever and wily.”

She also made sure to surround herself with a staff that shared her vision of unconditional love.

Markowitz is also driven by unending respect for the girls at Penny Lane. “When you think of what they have been through, you have to salute them just for still being alive,” she said.

That also drove her to ensure that Penny Lane would succeed.

“There were times, I’m sure she felt she may not make it,” Crigler said. “But there was never a time that she quit.”

Personal Best is a weekly profile of an ordinary person who does extraordinary things. Send suggestions on prospective candidates to Personal Best, Los Angeles Times, 20000 Prairie St., Chatsworth 91311. Or fax them to (818) 772-3338. Or e-mail them to valley@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.