Three Lonely Ladies

Democracy, someone once said, is the art of running the circus from the monkey cage.

I agree with that a lot of the time, especially when the system gets entangled in its own feet and begins to look like Kramer stumbling around Seinfeld’s apartment.

At other times I am privileged to see the true soul of democracy viewed from those quiet places of activity where the free will of the people is applied to its maintenance.

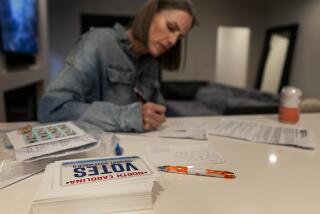

I’m talking about Tuesday’s election. I spent some time looking in on those who ran the polling places, mostly middle-aged women who wanted to be a part of the machinery that makes the country run.

It certainly isn’t the pay that draws them to a 13-hour day sitting in storefronts or garages, waiting for the voters to trail in.

They get $45 for doing it, $55 if they’re in charge of the polling place, an amount so low they’re classified as volunteers.

Almost 9,000 of them work the precincts for the city and an additional 4,000 for the county, and it’s damned tedious work at best.

They sit there checking names and addresses, handing out ballots, explaining the procedure, taking a lot of guff and then, at the end, making sure the vote count is correct.

If you’re in charge of the polling place, you end your work one or two hours after the polls close, tired but feeling good about your contribution to the spirit of Thomas Jefferson. Then the people in the monkey cage call.

*

The reason I know about those who work elections is because my wife, Cinelli, has been doing it for a lot of years.

She started out as one of the workers and then was placed in charge of a unit, giving time and energy toward the proposition that it’s the people, not the bureaucrats, who make America function.

The degree of her dedication to that principle was tested in 1993. Although fire was burning through the mountains around us, she remained at her post when no one else would, understanding that democracy has survived many fires because its citizens have stood firm, and she would too.

This was exceptionally difficult because our son’s home was in harm’s way and he was out fighting flames as high as heaven somewhere in the mountains. The stress of that day was intensified by her concern for his safety.

The other workers who had gone to check on their homes came back in time to finish up the day at the polling place. I remember looking in on them under a sky painted fiery red, three lonely ladies surrounded by calamity, bringing glory to a system that worked at their pleasure.

I also watched them Tuesday, bending with meticulous care to the task of making certain that proper procedures were followed, fielding complaints with understanding and humor, doing their best to do it right.

And I heard them say more than once with pride and satisfaction that this was their contribution to America. The phrase snapped like a flag in a breeze, held there by hands that rarely faltered.

*

The people in the monkey cage? They made themselves known several days before the election, delivering to the precincts material required to activate the polling places. In one case it came to Cinelli.

Then the bureaucracy began to reveal itself. Someone called to make certain the voting material had arrived and that the contents had been checked. She assured them it had. Then someone else called. And someone else. And someone else. And someone else. And someone else . . .

I can understand a double-check or even a triple-check, but when it gets to an octuple check, the whole thing smacks of bureaucratic vacuity, the stirring in the monkey cage that invariably makes things worse.

Once past that, a precinct officer must study or restudy the many elements of an election, complicated this time by a combined city-county operation at each balloting site. Then on the night before voting, the polling place has to be set up with booths and tables, a task that often goes until midnight.

I don’t know about other precinct officers, but my wife was up at 4:30 a.m. on election day to recheck everything. Her crew gathered at 7 and Democracy shone brightly. Their thanks? Well, someone from the county telephoned her two days later to complain about an omission that had nothing to do with her. His manner was hostile and accusatory, his understanding minimal.

When she mentioned it to a functionary in the county registrar’s office she was told not that he was wrong, but instead was informed snappishly that “Your name will be removed from the list of volunteers.” Click.

Too bad. Democracy works on a people level. It’s just when the dolts in the monkey cage get involved that Kramer starts stumbling over things.

Al Martinez can be reached online at al.martinez@latimes.com

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.