Deal OKd to End 30 Years of ‘Troubles’ in Northern Ireland

BELFAST, Northern Ireland — In the boldest bid at healing the wounds that still fester almost eight decades after Ireland’s partition, the leaders of Britain, the Irish Republic and local political parties on Good Friday signed a peace and power-sharing agreement meant to end bloodshed between this province’s Protestant and Roman Catholic communities.

Seventeen and a half hours after a self-imposed midnight deadline, and following repeated phone intervention by President Clinton, George J. Mitchell, the American chairman of the negotiations that began 22 months ago, was able to announce a landmark settlement.

“We can say to the men of violence across Northern Ireland, who disdain democracy, whose tools are bombs and bullets: ‘Your way is not the right way. You will not solve the problems of Northern Ireland, you will only make them worse,’ ” Mitchell, a former U.S. Senate majority leader, said in a speech carried live on television.

John Hume--the haggard but happy leader of Northern Ireland’s largest Catholic party, who didn’t sleep a wink as the talks reached their end--observed: “It’s been a long, hard road, but we have got there today. I think that for all our people, Good Friday will be a very good Friday.”

In the narrowest sense, the package deal, which proposes a power-sharing formula involving both majority Protestants and minority Catholics in a new Northern Ireland legislature and cabinet, is designed to curtail the three decades of “the Troubles” in this British-ruled province.

During that time, more than 3,200 civilians, police officers, British soldiers and guerrilla fighters have lost their lives.

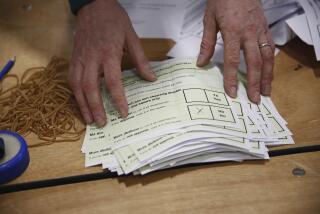

Before the accord comes into effect, voters on both sides of the Irish border must approve it in a referendum May 22.

In the larger sense, the deal brings the two Irelands closer than ever, since this island, for centuries under rule from London, was divided and the Irish Free State founded in the 26 predominantly Catholic counties of the island’s south in December 1921.

“Something amazing has happened--it’s truly a new and golden opportunity,” David Ervine, whose Progressive Unionist Party is linked to Protestant paramilitaries, mused as it became clear that agreement was near. He compared Friday’s events to the razing of the Berlin Wall.

The breakthrough was the greatest political and diplomatic success yet for British Prime Minister Tony Blair, elected last May in a Labor Party landslide.

On Dec. 11, in a gamble that paid off this week, Blair became the first British prime minister since 1922 to receive Irish nationalists at his official Downing Street residence.

On Tuesday, the 44-year-old British leader flew here from London and toiled in his shirt sleeves with other participants in the talks, including “the Taoiseach,” or Irish prime minister, Bertie Ahern, who temporarily returned to Dublin on Wednesday to bury his mother.

Some Irish newspapers likened Blair to William Gladstone, his great 19th century predecessor and a champion of Irish home rule.

But Blair made clear that the task of bringing peace to Northern Ireland and its 1.6 million people is not over.

“Today, we have just a sense of the prize that is before us,” he said. “The work to win that prize goes on. We cannot, we must not, let it slip from our grasp.”

Implementation to Be Difficult, Many Say

Prudent after a quarter of a century of abortive efforts to curb communal violence and polarization in this land about the size of Connecticut, many participants in the talks stressed that putting together the peace deal and implementing it will be very different things.

A copy of the agreement is to be sent to every household in the British-ruled province over the next two weeks, before it is voted on in the May referendum.

But given the long, conflict-ridden history of Irish-British relations, which began when Norman soldiers from Britain came ashore in 1170 and ended with Ireland as a longtime possession of the British crown, just getting the politicians to agree seemed a colossal achievement.

“It’s almost impossible to overstate what’s been achieved here--it supersedes everything, maybe going back 400 years,” a stunned Dennis Murray, the BBC’s Belfast correspondent, told his viewers from the talks site at the Stormont government buildings outside Belfast.

Provincial Assembly Among Terms of Deal

The text of the deal was not immediately released. But British government and other sources said it includes:

* A new provincial assembly with 108 legislators and a 12-member Cabinet, to be elected in June. It would serve as a vehicle for power-sharing for the first time between Northern Ireland’s 54% Protestant majority and its 43% Catholic minority. The old provincial legislature, abolished by the British in 1972, was dominated by pro-British Protestant unionists, and it long discriminated against Catholics in housing, employment, voting rights and other areas. For the past 26 years, the province has been under direct rule from London.

* The new assembly, in concert with the Dublin-based Parliament of the Republic of Ireland, would form a cross-border North-South Council in a year to coordinate policies across Ireland. These areas could include culture, industrial development, consumer affairs, agriculture and fisheries, trade, transport, public welfare and education. If the assembly and Dail concurred, the council could take actions for all of Ireland, marking the first time since the end of British rule in the south that there would be some form of island-wide executive body.

* The Irish government will seek support among its citizens for a revision of Articles 2 and 3 of their 1937 constitution. As it now stands, that document defines Ireland as the entire island and calls for “re-integration” of the six counties of Northern Ireland. The constitution would be amended to specify that Irish reunification will come about only if a clear majority in Northern Ireland desires it.

* A Council of the Isles would link governments in Belfast and Dublin and the new legislative assemblies that are being set up in Scotland and Wales as part of a devolution of power from Parliament in London. “I think we stand on the brink, not only of repairing relationships in this island, north and south, but throughout these islands,” said John Alderdice, leader of Northern Ireland’s leading inter-communal party, the Alliance Party.

Some of those who negotiated Friday’s accord were sworn enemies, adding to the euphoria and incredulity felt by the 400 journalists who milled around the talks site waiting for the end.

David Trimble and the rest of the pro-British Ulster Unionist Party wouldn’t even talk to Gerry Adams and other delegates from Sinn Fein, the political wing of the Irish Republican Army, which began fighting in 1970 to overthrow British rule in the province. Eight months ago, Sinn Fein was allowed into the talks after the IRA implemented a truce.

“We are here reaching out the hand of friendship,” the bearded, 49-year-old Adams said Friday, though he added that Sinn Fein’s goal remains a united Ireland.

Three Decades of a Deadly Conflict

Since “the Troubles” began after a mass civil rights campaign by the Catholic minority in 1968-69, Northern Ireland has been rocked by more than 10,000 explosions, 2,600 attacks on police stations and 2,000 “punishment” shootings--most often a bullet intended to cripple fired into the victim’s kneecap.

More than 30,000 people have been injured, and 250 outside the province--in Britain, the Irish Republic and continental Europe--have been killed. One of the most noteworthy casualties was Lord Mountbatten, whose yacht was blown up by an IRA bomb off the coast of County Sligo on Aug. 27, 1979.

The IRA was responsible for most of the deaths. But loyalists--fighters “loyal” to the preservation of Northern Ireland as an integral part of the United Kingdom--were behind the worst single day of killing. That was May 17, 1974, when three car bombs in Dublin and another in Monaghan claimed the lives of 33 people, including two babies.

An earlier formula for Northern Ireland’s two communities to share government posts was signed in 1973. But it collapsed after five months when unionist power workers brought the province to the verge of collapse, fearing that the new cross-border “Council of Ireland,” similar to the institution approved Friday, would lead to union with the south.

Ironically, Trimble, the present-day leader of the Ulster Unionists, the largest party in Northern Ireland and a participant in the Mitchell-led negotiations, was one of the 1973 plan’s leading foes.

Friday’s agreement was held up for a few more hours because of last-minute fears by the Ulster Unionists that the power-sharing agreement might award posts “in the heart of the administration” to Sinn Fein, even if the IRA breaks its cease-fire. Assurances from Blair assuaged him, Trimble said.

In fact, it may have been Sinn Fein that gave up the most in an all-or-nothing agreement that grants the provincial legislature, a body whose authority the republicans had contested as an emanation of British rule, partial control over the North-South Council.

But Adams made clear that Friday’s package had to be approved by his party’s rank and file. A refusal by Sinn Fein will probably set the spiral of communal violence in motion again.

Trimble, meanwhile, said he will also have to consult the grass roots of his party, which accounts for 33% of the Northern Ireland electorate.

“It will be an incredible deal if it manages to encompass the leader of the Ulster Unionists and Sinn Fein--incredible,” said Ed Curran, editor of the Belfast Telegraph newspaper.

In 1985, the British and Irish governments signed an agreement to give the Dublin government a right of purview over Northern Ireland affairs when the rights of the Catholic community were at issue. That was opposed both by Sinn Fein and by the unionists, who resigned en masse from the British Parliament in Westminster. The Anglo-Irish agreement never was applied.

This time around, some of the most nettlesome issues have been deferred. An independent commission, still to be named, is supposed to monitor and verify the surrender of guns, mortars, plastic explosives and other weaponry from the IRA and loyalist paramilitaries and to recommend whether there should be a change in the status of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, a 90% Protestant police force accused by many Catholics of being biased and brutal.

The 242 loyalist and 236 republican prisoners in British jails could also be given reduced sentences if their organizations obey a cease-fire. All could be out in two years, officials said.

“This agreement deals fairly with the people of Ireland, north and south,” Mitchell said in his televised remarks. Ireland’s foreign minister, David Andrews, said the settlement “means those who would seek to kill and maim will be sidelined.”

* IRISH EYES IN L.A.: Jubilation in Los Angeles over the peace accord. A9

* PRESIDENTIAL CALLS: Clinton kept the phone lines humming as talks paid off. A9

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Breakthrough on Belfast

The breakthrough--the biggest of its kind since conflict engulfed Northern Ireland in 1969--capped a negotiating marathon driven by U.S. mediator George Mitchell, and the prime ministers of Britain and Ireland.

****

“The people of Northern Ireland will make the difference. . . . The choice is yours.

--U.S. Mediator George J. Mitchell

*

“I see a great opportunity for us to start the healing process here in Northern Ireland.”

--David Trimble, leader of the pro-British Ulster Unionists

*

“There are good things in it, there are bad things in it that people will have to get their heads around.”

--Gerry Adams of Sinn Fein

****

The Deal: Among its provisions, the agreement would create a new power-sharing assembly and cabinet in Northern Ireland and a cross-border council to coordinate policies across Ireland.

The Process: A referendum on the accord will be held on both sides of the Irish border May 22, and leaders of opposing factions in Northern Ireland say they must pose the accord to their constituencies.

The Question: Can the accord survive the ratification process and the memory of decades of strife between Catholics and Protestants?

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

How It Would Work

The Northern Ireland accord, still subject to approval, would create three interconnected bodies of government.

NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY: Elections in June for a 108-seat assembly. Checks and balances require Protestants and Catholics to share power and responsibilities. Powers now administered by Britain’s Northern Ireland Office will not be handed back to local politicians until early 1999--but only if the assembly members agree on how to participate in the North-South Council.

NORTH-SOUTH COUNCIL: A forum for ministers from the Irish Republic’s government to promote joint policy-making with the new Northern Ireland assembly. Will have powers to implement all-Ireland policies but only with the approval of both the Northern Ireland assembly and the Irish parliament in Dublin.

COUNCIL OF THE ISLES: Lawmakers from the Irish Republic will meet regularly with members of the British Parliament from London, the Northern Ireland assembly, and with representatives of the new parliament for Scotland and assembly for Wales. This body will have no administrative or legislative powers.

Associated Press

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Ireland Facts

The island known as Ireland consists of the Republic of Ireland, a self-governing nation, and Northern Ireland, which is ruled by Britain. The pact reached Friday takes a big step toward reunification.

POPULATION

Northern Ireland: 1.6 million

Republic of Ireland: 3.5 million

*

RELIGION

Northern Ireland: 43% Roman Catholic, 54% Protestant

Republic of Ireland: 95% Roman Catholic, 5% Protestant

*

GOVERNMENT

Northern Ireland: Direct rule from London

Republic of Ireland: A republic, with a Parliament and constitution

*

THE SPLIT

A 1920 act of British Parliament divided Northern and Southern Ireland. Each had its own parliament and government. In 1921, the southern part became a dominion and eventually the independent Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland chose to remain part of the United Kingdom. It elects 17 members to the British House of Commons.

Sources: The World Almanac, World Book, Associated Press

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.