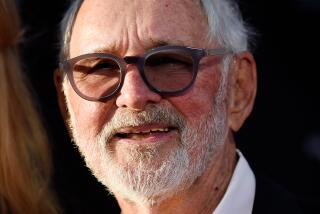

Literary Producer Opens a New Chapter

Peter Samuelson has the dubious distinction of having his latest film, “Arlington Road,” starring Jeff Bridges and Tim Robbins, targeted for release through PolyGram Filmed Entertainment just as the movie company is expected to be sold.

Such is the life of an independent producer, a role Samuelson calls “the most difficult thing in the world and also the most rewarding.”

For him, “Arlington Road” is a particularly significant undertaking because it’s the first mainstream American movie produced by the Anglo-American film outfit that he runs from his pink mansion in Westwood and that his younger brother, Marc, heads in London.

Their first endeavors, the critically acclaimed specialty films “Tom & Viv,” released by Miramax Films, and “Wilde,” currently in release through Sony Classics and starring Stephen Fry as the flamboyant literary genius Oscar Wilde, were low-cost British productions aimed at highbrow audiences.

“Arlington Road,” a $30-million thriller financed by Lakeshore Entertainment, is meant to have a broader appeal and represents the kind of bigger-budget commercial material that the Samuelsons want to complement their slate of smaller-scale British and European films.

Now in the final stages of post-production, “Arlington Road” still lacks a firm release date, though PolyGram Films Distribution President Bill Soady said it’s slated for early 1999.

The fate of the film is as much up in the air as the future of PolyGram itself. Various bidders are circling PolyGram’s film division, which Seagram Co. is auctioning off to help finance its $10.4-billion acquisition of the Dutch-owned music giant. A sale could be finalized by late fall.

Yet Samuelson says he’s undaunted by the uncertainty and has nothing but praise for how PolyGram executives have handled his film.

“I believe ‘Arlington Road’ is a very commercial film and whoever the professionals are who control its release, I’m sure it will be in their best interest to support it.” The film, directed by Mark Pellington and produced by the Samuelsons and Tom Gorai, is a psychological thriller about two Washington neighbors whose lives become entangled when one suspects the other of being evil.

It would take more than a murky release date to rattle someone like Samuelson, 47, whose philanthropic efforts as the founding head of two major children’s charities--the Starlight Foundation, which grants wishes to seriously ill children, and its sister charity, Starbright--add perspective to the often crazy-making ways of Hollywood.

“In this challenging business of being a producer, it gives me a sense of values,” said Samuelson, as he recalled being on a movie set when a production crisis erupted while he was on a conference call trying to figure out how to grant a sick child her wish of seeing a rainbow.

“How can you be concerned about a production delay?” asked Samuelson. “Both things are important, but one gives perspective to the other.”

While “Arlington Road” nears completion, the Samuelsons are busy with other projects, including a biographical film about Winston Churchill that is being developed by Brian Gilbert and Julian Mitchell, the director-screenwriter team behind “Wilde.”

The two projects the Samuelsons have earmarked as their next American productions are “Wild Horses,” a modern female western, and “Save Me Joe Lewis,” a crime drama adapted and to be directed by John Roberts (“Pauly”) from a novel by Madison Smartt Bell.

The projects will probably be funded through a combination of foreign pre-sales, domestic distribution deals and other third-party financing set up by the brothers, who own the copyrights to their films.

Samuelson said “Tom & Viv,” which cost $5.1 million, was profitable, generating worldwide theatrical sales (including the domestic sale to Miramax) of $7 million. He also expects to see some return on “Wilde,” made for $10 million. Total receipts, to date, have surpassed $9 million.

The producer suggested that while the landscape for independent producers is better today than it was when he began, “it’s still hideously difficult” and that Hollywood is “very much a town of ‘What have you done for me lately?’ ” A good reception to their previous films drew more than the usual attention to their company at this year’s Cannes Film Festival.

Born and raised in the London suburb of Hampstead and the eldest of three sons, Samuelson attended Cambridge University on an English literature scholarship. The Samuelsons come from a family with deep roots in show business going back to the early 1900s, when their grandfather, G.B. Samuelson, a famous British silent film producer, came to Los Angeles to make movies but went bust when the talkies came in.

Their father and his three brothers founded the Samuelson Group, a successful camera rental company, in 1950. They took it public in the mid-1960s and sold it profitably in 1987.

A year before going to Cambridge, Peter Samuelson initiated his movie career as a French-English interpreter on “Le Mans,” starring Steve McQueen. After graduating college, he worked as a production manager on various films, including 1974’s “Return of the Pink Panther.” A year later, he accepted a one-year contract to become a producer for a Hollywood-based commercials company and wound up “just sort of staying.” When he couldn’t get into the Directors Guild as a production manager because his work experience was overseas, Samuelson simply “promoted myself to producer.”

He partnered with actor Donald Sutherland on several Canadian productions, among them “A Man, a Woman and a Bank.” When the financing he arranged fell apart due to a change in Canadian tax-shelter laws, “all my little doctors and dentists that put up the money were suddenly absent.”

After reading a front-page article in The Times about a young man named Ted Field who had just inherited several hundred million dollars as an heir to the Marshall Field fortune, he wrote him a letter.

“I can remember my secretary raising her eyebrows that we had sunk to the point of writing cold-call letters to people we read about in the newspapers,” Samuelson said.

It worked. Field, 25 at the time and attending Pomona College, remembers being so impressed with how “intelligent” Samuelson sounded in his letter that he agreed to have lunch. Then he agreed to put up the missing half of the budget. After the film was completed, he proposed that the two of them go into the movie business together.

Samuelson headed the film division of Field’s company, Interscope Communications, for four years until 1984, then spent a year on the corporate side, where he helped engineer Field’s $40-million acquisition of Panavision.

“I have nothing but great things to say about Peter’s integrity and intelligence,” said Field, who made a killing four years later when he sold the camera giant for $100 million.

Samuelson, who maintains dual citizenship, suggests that “one way of looking at what we do is a kind of cultural and commercial arbitrage. . . . We’re friendly Americans to the Brits and friendly Brits to the Americans.”

After his grandfather went bankrupt, Samuelson said the old man “strictly prohibited my father’s generation from being producers because he thought it was too risky. He said, ‘Do something where they hire you, it’s safer. So, they did. . . . But I never knew him. So, I’m a producer.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.