Mariners Didn’t Extend His Contract, so a Bitter Johnson Is Resigned to Leaving Seattle After the Season

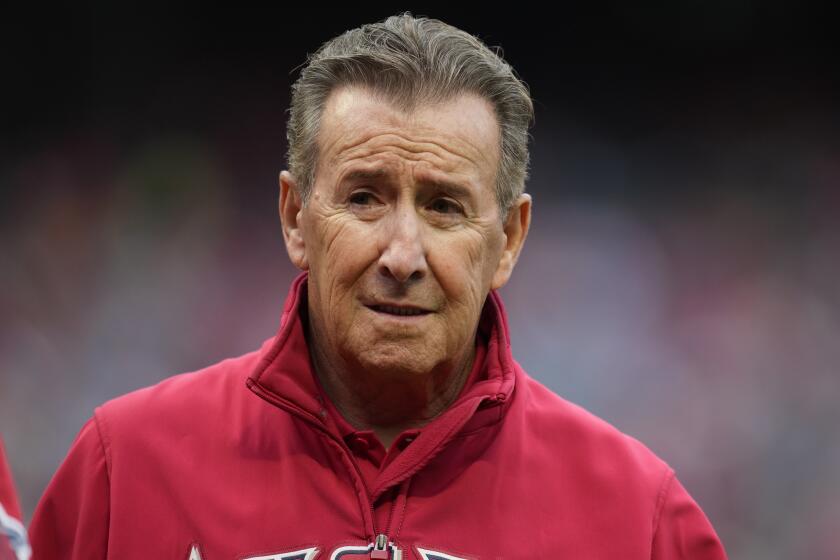

PEORIA, Ariz. — Randy Johnson has become an institution in Seattle, as permanent a fixture on the city’s skyline as the Space Needle, and now it appears the Mariners are taking a wrecking ball to this 6-foot-10 pillar of pitching.

The Big Unit is in Seattle’s camp, his hair as long and scraggly, his glare as icy, and his fastball as scary as ever.

But after a winter of discontent, when the Mariners would not extend Johnson’s contract and sought to trade the left-hander, it’s looking more and more as if Johnson’s glorious run in the Pacific Northwest will soon end.

“I have no reason to think I’ll end my career here,” Johnson said, his voice hinting of bitterness and resignation. “It’s over and done with. They told me they have no intention of giving me an extension. That’s like me telling my wife I want a divorce and not leaving.

“I’m here, I’ll do my job to the best of my ability, but if I’m not here [in the near future], it’s not because of something I’ve done. . . . I have all the reasons to want to stay in Seattle. My wife’s family is from there, the fans have been great. I don’t want to be traded. I’m just disappointed with everything that’s happened here.”

The winter trade talk--the New York Yankees, Cleveland Indians and Dodgers reportedly were most interested in acquiring Johnson--has carried into spring, and now comes more speculation: If he stays, will Johnson be a clubhouse distraction? Will his frustration detract from his performance?

Don’t bet on it.

“If anything, it will give him more incentive to show those guys he’s worthy of a long-term contract, to stick it to them and show they made a mistake,” Angel shortstop Gary DiSarcina said. “And the last thing he needs is more incentive.”

Johnson considered holding out this spring but decided against it. His first day in camp, he issued a written statement saying he “will focus all my energies on winning a world championship for Seattle fans.” Wanting the controversy to die, he asked that media questions “focus on the present, and the Mariners’ goal of winning the World Series.”

But it’s obvious Johnson is still upset, because even when not asked specifically about his future and the trade rumors, the subjects creep into replies to other questions.

“It seems like every spring they’ve talked about trading me,” said Johnson, who was, indeed, the focus of trade talks in 1993 and ’95. “How’s that going to make me feel? I have legitimate reasons to be upset, but I’m trying to be the bigger man here.

“I’m a professional, I’ve worked hard to get back to this level after [1996] back surgery. I have a lot of respect from my peers, and I’m not going to jeopardize that by not showing up for camp, because that would only hinder my performance during the season.”

How confusing this must be for Mariner fans, who saw Johnson practically save the franchise by pitching his heart out to lead Seattle to the 1995 American League championship series.

There was talk that summer of the Mariners’ being sold and possibly moved, but the state legislature got so wrapped up in the Mariners’ emotional run to their first division title, it voted to approve a public funding package for a new stadium, scheduled to open in 1999.

Johnson went 18-2 that season, won the Cy Young Award, pitched Seattle to a 9-1 victory over the Angels in a one-game playoff for the West championship and won two games--one in relief--in the dramatic division series victory over the Yankees.

An ailing back limited him to eight starts in 1996, but Johnson returned from surgery to go 20-4 with a 2.28 earned-run average and 291 strikeouts last season, leading Seattle to another division title. The 34-year-old with a 98-mph fastball and vicious slider is 75-20 over the past five seasons and is regarded by many as the best pitcher in baseball.

In Atlanta, that kind of success earned Greg Maddux a five-year, $57.5-million contract last season. In Baltimore, it earned Mike Mussina a three-year, $20.5-million extension. In Seattle, it has earned Johnson a shove out the door.

How did it come to this?

Johnson had an inkling his relationship with the Mariners might sour when the team waited until last September, long after he proved he was healthy, to pick up his $6-million option for 1998.

Johnson wanted an extension, reportedly something along the lines of Maddux’s deal, but Mariner President Chuck Armstrong said to extend Johnson’s contract with another year remaining on his current deal “is not a good investment,” and he announced in November the Mariners would “entertain offers” for Johnson.

The winningest pitcher in franchise history took that to mean he was no longer wanted, and his emotional detachment from Seattle began.

“I’m not trying to set new salary standards; what I’m looking for in this game is security, which is no different from what any athlete or working person wants,” Johnson said. “I’ll work hard this year and things will take care of themselves, but I feel a little slighted. I brought a lot to the table for the Mariners, and I haven’t got the same back from them.”

There is another side to this dilemma: If you were the Mariners, would you commit $50 million to a 34-year-old power pitcher who had major back surgery in 1996?

The Seattle Times did a recent study of power pitchers beyond their mid-30s and found that many, such as Nolan Ryan, Steve Carlton, Bob Gibson and Tom Seaver, were highly effective after age 34.

But then there was Juan Marichal, who went 18-11 in 1971 at age 33 but slipped to 6-16 in ’72 and 11-15 in ’73. And Mike Scott, who had a 20-win season in 1989 at age 33, only to fall to 9-13 in ‘90, 0-2 in ’91 and out of baseball in ’92. And look what happened to Mark Langston, now 37, in his last two seasons with the Angels?

It’s a no-win situation for the Mariners: Sign the Big Unit and risk Johnson re-injuring himself and costing the team millions. Trade him and risk alienating fans and having Johnson go elsewhere and dominate, much the way Ryan did after then-Angel General Manager Buzzie Bavasi, who refused to give Ryan $1 million after the 1980 season, said he could get “two 8-9 pitchers” to replace Ryan at half the price. Don’t trade him and risk getting nothing in return if he leaves as a free agent.

“It’s a very interesting situation,” Seattle pitcher Jamie Moyer said. “I find myself thinking, ‘What would I do if I was the player? What would I do if I was the organization?’ I can see the team’s point of view, but looking at the business as a whole, in most situations teams want to sign their marquee players.”

There seems to be a compromise somewhere--perhaps a two-year deal with an option for a third year?--but Johnson seemed most turned off by Seattle’s refusal to even discuss an extension this winter and the team’s thinking that his back is still a concern.

“I don’t think anyone will be convinced I’m thoroughly healthy--obviously the Mariners don’t, or I’d have an extension by now,” Johnson said. “It’s not like my fastball has decreased 10 mph.

“My back gave out and it was corrected. I missed one start last year because of my back. Until I miss a bunch of consecutive starts, I don’t consider myself a risk. I’m totally healthy and in the prime of my career.”

Johnson may seem too old to be in his prime, but he was a late bloomer. He was more Mitch Williams than Steve Carlton as a youngster, and he led the American League in walks with 120 in 1990, 152 in ’91 and 144 in ’92.

His raw power was unrivaled, but Johnson--and hitters--never knew where his pitches were going. The former USC pitcher was something of a curiosity, a guy who might walk 13 one game and throw a no-hitter the next.

But a confluence of events in 1993, around the time his father died--he and his wife decided to start a family (they now have two kids, and a third is due soon), and Ryan and pitching coach Tom House gave him some valuable advice--helped transform Johnson from Wild Thing to The Untouchable.

From 1993 through last season, Johnson complemented his 75-20 record with a 2.87 earned-run average, 1,182 strikeouts, including 308 in ‘93, and only 338 walks.

“They helped me make a small mechanical change, to land on the ball of my front foot instead of the heel,” Johnson said of Ryan and House. “That was the first of many dominoes that started tumbling in my life that manifested in me becoming the best pitcher I could be.”

The death of his father, Johnson said, changed his mental outlook. “I refocused and started bearing down more,” Johnson said. “It put things in a different perspective. Certain pressure situations, like having the bases loaded with no outs, didn’t seem so tough. To me, life and death was a pressure situation.

“I worked harder, and my family grounded me more. I just realized I’m not going to be playing baseball the rest of my life. I have a great gift; I had to use it to the best of my ability.”

Most figured the gift would keep on giving in Seattle. Now the Mariners may pull the plug on the Big Unit, and you can hear the cheering all the way down the West Coast.

“I don’t think you’ll see a lot of tears around here if he went to another division or the National League,” Angel Manager Terry Collins said.

There will be a few in Seattle, though. Mariner fans wish they could double-click this icon and make Johnson appear, year after year, but Johnson seems ready to file his Mariner career to memory.

“I never felt I was treated as well as I should have been here, but there’s no sense digging up old things--I’ve put them behind me,” Johnson said. “I heard the trade rumors this winter, so I think there’s a few teams out there who want me.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Record: 65-38, .631

ERA: 3.01

Strikeouts per 9 IP: 9.57

Hits per 9 IP: 6.93

Record: 61-46, .570

ERA: 3.32

Strikeouts per 9 IP: 9.00

Hits per 9 IP: 7.67

Record: 89-33, .730

ERA: 2.13

Strikeouts per 9 IP: 6.87

Hits per 9 IP: 7.39

Record: 75-20, .789

ERA: 2.87

Strikeouts per 9 IP: 11.59

Hits per 9 IP: 6.58

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.